Can CBR bring down lending rates for affordable capital?

What you need to know:

- For some time now, the Central Bank Rate (CBR) reduction has not been corresponding with commercial bank interest rates.

- Julius Mukunda expounds on whether the CBR can deliver lower lending rates in the economy.

According to the Budget Strategy for the FY 2018/19, economic growth for the FY 2016/17 was 3.9 per cent, below the National Development Plan (NDP II) expected average of 6.3 per cent. Uganda’s growth over the last five years is much slower than the historical average and regional peer average. The 2016/17 slowdown in growth is largely attributed to constraints to private sector growth and adverse weather, which negatively affected outputs, and consequently incomes and consumption of majority of households. Whereas the NDP II target for private sector growth is to reach 15.4 per cent by 2020, it was still low at 7.5 per cent citing challenges including high costs of electricity, capital/development finance (access to credit) and transportation which have rendered local manufacturing uncompetitive.

The above facts notwithstanding, government continued to borrow domestically in the FY 2016/17, further making it difficult for the private sector to access affordable financing for investment. In the FY 2016/17, government borrowed Shs603b from the economy yet the same economy provided credit of up to Shs659b in the FY 2016/17.

Private sector credit

Private sector credit grew at 5 per cent (in nominal terms) compared to government domestic debt at 2 per cent in FY 2016/17. However, government remains the biggest borrower from the domestic market contrary to the Public Debt Management Framework. Adjusted for inflation, private sector credit growth was negative.

The credit provided to the private sector is mostly got from the commercial banks, yet the government also borrows from commercial banks. Other factors constant, if government did not borrow from the commercial banks, there would be an extra Shs603b for the private sector to borrow and invest. One also needs to note that Uganda private sector credit to Gross Domestic Product (GDP) at about 13-14 per cent is nearly half the EAC average (excluding Uganda) and the emerging economies average of more than 40 per cent. This implies Uganda’s private sector is under-leveraged.

Source of funds

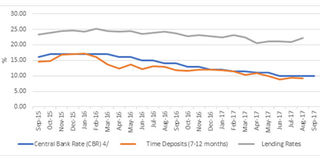

For some time now, it has been pointed out that the banks have a multiplicity of other sources of funds to lend that are expensive, coupled with the high-risk profile and high costs of doing business in the economy and as such warrant the high lending rates on the market. However, one of the sources of the credit (the time deposits) do not seem to influence the lending rates enough as the graph about relationship between lending rates, time deposit CBR shows. The ratio of total deposits to loans remains above one, and grew to 1.4 in December 2016. Shareholders equity as source of finance is miniscule - with total shareholders’ equity at Shs3.7 trillion (16 per cent of the total bank assets). So, in short, deposits are a major source of financing for the banks. What also comes out clearly is that since the institution of the Credit Reference Bureau, operationalisation of the commercial court and now the National Identification system, there seems to be no positive response from the banks to reduce the risk profile to the customers in all categories as usually profiled.

Infrastructure investments

On the fiscal front, there has been intense investment by government in infrastructure (both transport and energy) that should be factoring into reduced cost of business (to counter one of the excuses/good reason fronted by banks). Over the past four financial years, Shs2.7 trillion was spent on the energy and Minerals development sector while Shs9.276b was spent on the works and transport sector. This expenditure notwithstanding, according to the World Bank, Uganda loses $300 million annually due to public inefficiencies and public investment efficiency in Uganda stands between 0.33 and 0.36, implying that more than 60 per cent of the resources invested in public projects go to waste. This needs to be looked at in wake of the expenditure on NIRA and the National ID project as efforts further identify Ugandans to reduce the risk of fraud. With all this colossal public expenditure, we still have banks citing cost of doing business in terms of accessibility of some locations in Uganda and cost of commercial electricity for operations and this puts the consumer/customer who doubles as the tax payer as the net loser.

We have also observed that the 24 banks and a multiplicity of credit institutions have not reflected the lower lending rates. This is because the assumption that there would be competition among the banks and eventually drive the lending rates down was totally flawed. We have a strong resemblance of an oligopoly market structure positioned as perfect competition. According to published statements, the commercial profits grew to Shs677b (for all the 24 banks) but the top eight banks enjoyed profitability of Shs635b (94 per cent of total profits) in 2016. Thus, the struggle at the bottom remains and four banks were loss-making in the same year.

Other interventions to avail affordable credit for investment such as the Uganda Development Bank, the Agriculture Credit Facility, the Youth Livelihood Fund, Women’s Entrepreneurship Fund and a multiplicity of project funding for special interest groups to invest have all since failed to deliver due to poor implementation, funding and politicisation; and this seems to be the unfortunate trend of fiscal and political efforts to address the credit for the investment question in Uganda.

As it were, to have the CBR as the main stream tool to reduce lending rates comes off as an academic exercise. The reality in the Ugandan economy reveals that as a priority, the expenditure by government to relieve the economy of the infrastructure bottle necks needs to manifest its worth. The CBR alone has demonstrated that it cannot cajole lending institutions to reduce the lending rates in the economy since they (financial institutions) demonstrate reasons that are hard to ignore; as to why the rates are still high.

When we consider the operational and other costs that commercial banks have to incur, we should not expect miracles from the CBR in terms of lower lending rates. The only policy option that would reduce the lending rates without adequately addressing the structural bottle necks would be to increase regulation in the financial sub sector, even to the extent of capping interest rates; a position that government has continuously shied away from as it depicts a policy reversal from the “liberalisation” of the economy. It is, therefore, not avoidable anymore for the fiscal policy side to deliver otherwise the monetary policy will continue to be a paper tiger in regard to reducing lending rates in Uganda and enabling affordable investment capital.

Julius Mukunda is the executive director of Civil Society Budget Advocacy Group.