A night with the lost boys of Kisugu

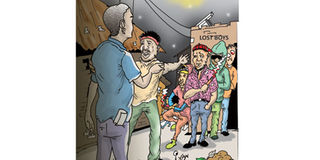

The writer meets the Lost Boys in Kisugu, a city suburb. ILLUSTRATIONS BY IVAN SENYONJO

What you need to know:

- They are about eight each with a target to accomplish at the end of the day. They snatch valuables from car passengers, passers-by and others who look like potential ‘clients’ and run away with the loot to share the spoils. They call themselves the Lost Boys in Kisugu and they had a chat with DERRICK WANDERA.

Time check, 9.30pm on Thursday. My guide Charles Kalule leads the way as I slowly follow him. From a distance, the chuckles of drunk men waft in from different directions as we approach a busy centre within Kisugu. This is one of the big seven slums in Central Kampala.

The place is a hub of merrymakers. A cocktail of deafening music fills the air. Every kiosk is a drinking spot and different people engage in loud conversations; one can hardly hear their neighbour.

“This is Kasanvu Centre,” says Kalule, almost screaming into my ears.

“Where are we heading to next?” I reply.

“Kakana mzee (loosely translated as keep calm man),” he tells me.

He then leads me to a big hall with a few scattered benches and plastic chairs, the occupants of the room are four young girls with sunken eyes, who look to be in their 20s. Clad in simple long dresses that look a little old, the girls seem worried and hungry. I’m offered a seat in front of them and we strike a conversation from which I learn that they are from the vicinity. I get to know what the slum looks like at night.

Sharing from experience

Grace Nakiwala, a Senior Two dropout ,tells of how her father could not afford tuition due to his ill health. “Now, I do domestic chores in different homes to raise money to look after my sick father and pay rent.” Also, she had been molested on several occasions and taken advantage of by men and boys. She recounts the time she almost lost her life to a gang in this slum.

“They almost killed me, they beat me up. One night as I moved, I stumbled on a gang of men who took my handbag with a phone and Shs60, 000 - my day’s wage. They beat me up severely,” Nakiwala recounts, almost shedding a tear.

Farida Magoba, 17, shares that at 11, she lost her virginity to a rapist in one of the dark corners of the slum. She has never forgiven herself for passing through that corner and loathes them.

“I was raped but when I told people, they did not believe me. I have lived with the trauma and never forgotten that incident,” she reminisced.

Surprisingly, the four girls almost had similar stories, which portrayed the plight of being girls in a slum. From the girls’ accounts, I was intrigued to explore life in this area.

Going to the mafia empire

Kalule knows some of such youth by name. He leads the way. We trudge narrow dark corridors with uneven footpaths. Then through the darker patches of the “streets”, I cannot help but watch my steps as there are many suspicious clusters of young people who make animated gestures and I imagine them attacking us.

The Slum Settlement in Kampala, a survey by Ministry of Lands, Housing and Urban Development on the Kampala Central slum profile indicates that of the seven slums in Kampala Central, only one is serviced with street lights.

Walking past a corner near an incomplete building, seven young men stand. As we walk towards them, they murmur, some throw their hands in the air and they suddenly stand arms akimbo. Some of them don sweaters whose hoodies cover half their faces, others wear caps facing backwards and the rest have bandannas tied on their heads. We draw closer. They fidget to put out the small glowing red lights between their fingers (cigarettes) but the cloud of smoke floats.

An unusual smell hits my nose and I almost lose balance for a moment, but I carry on. Our hosts of the night speak Luganda (modified with street speak).

“Mwana muli ne Kakooza ? Have you come with a police officer?”) a random voice calls out from the group. Sparko, a middle-aged youth with an athletic build, perhaps in his late 20s, is wearing a hat and black plaid shirt tucked into a black pair of jeans, steps forward. With a husky voice, he assertively introduces himself as the group leader.

“This is our group. We are called the Lost boys,” Sparko says. Indeed on a towering wall behind them is a big inscription Lost Boys. He delegates Rato to take us around “their territory” and the rest follow as they giggle and mumble.

Touring their zone

Kalule and I wait for the next move as two girls walk past us. One of the boys whistles in the girls’ direction and one other hisses.

“Mwana kilikitya? (loosely translated, how are those [girls]?),” he asks and giggles.

Sparko turns and looks at the two girls wearing skinny jeans and tight sleeveless tops. A deafening silence befalls us. I notice that the boys are looking in the girls’ direction. I become a helpless team player.

“Hey guys!” Sparko calls out as one of the big boys advances towards the girl, “This is not what we are here for today.”

Rato, a lanky young man with a small legs, head bent forward, steps ahead of us. He has a high-pitched voice and speaks fast. He walks ahead of us like a tour guide.

“We have done this for some time,” he says, adding, “It is because of joblessness that we end up doing these bad things.”

“What do you do in particular?” I ask.

“Aaahh, you know…we grab bags, phones, money, beat up people. In fact, you can hire us if you have an enemy and we shall do a good job. That is if you pay us well,” he says.

“How much would I have to pay to have my enemy flogged?”

“Depending on what you want,” Jaguar interjects. He has a well-trimmed O-shaped moustache, “We do not kill! If you want him to just be taught a lesson, you pay Shs3,000 or Shs5,000. If you want us to bring you the tooth of that person, you pay slightly higher.”

“How much?” I probed.

“That can be like Shs10,000 or Shs15,000,” Sparko says as we approach a dark passage between two houses.

“For those we find with bags and they try to resist, we bring them here and hold them kabadia (near strangle) so that they can let go of what they have,” Sparko explains as he leads us to their execution ground.

Following a wide channel with a pungent smell and black water flowing under it, we reach a darker place with two abandoned houses and a small quadrangle. Sparko says it is where their biggest executions such as rape and robberies take place. As I scan the place, I can only spot a white piece of cloth. On closer examination, it is torn knickers. My heart leaps as I wonder whether this could have been for one of their victims.

“So, we get girls and bring them here. Even if someone is chasing us, they risk falling into the sewage channel. After taking the intoxicating substances, there is a world we go to and it makes different demands, depending on what you have smoked,” Begga, the hulk of the Lost Boys says in a shaky voice.

Who are the Lost Boys?

Sometime in 2005, six boys were sharing a small room in Namuwongo after they had dropped out of various schools in the city. Having failed to get something from which they could earn a living, they resorted to washing cars. From this, they earned what could take them through the day. As time went by, their income was not adding up because they had started using drugs, a habit they pick from being idle.

“Customers were not coming in as we expected. We were using some drugs because we had a lot of time on our hands for the rest of the day,” deep-voiced Menso, one of the gang members recalls. He sounds remorseful.

“Some of us do not like what we are going through but because this is what life has subjected us to, we have no choice. I do not enjoy grabbing people’s bags or money or phones, but I’m jobless and I do not have any source of income,” he adds, almost breaking down.

As they started growing in number, they relocated to where they live and they are 30 altogether. Over time, they have recruited and lost some members who have formed other groups elsewhere.

Their loot

Whenever they get their loot, they gather to share the spoils or if they have to sell an item, one of them is assigned to go downtown where they normally sell such.

One day, after Lost Boys got a big sum of money from a woman whose bag was near a car window. They had a scuffle about how they should share the Shs1.2m that was in the bag. It was after this incident that they started to share.

“We have fought among ourselves and in turn have lost some of our members. We normally fight over sharing our ‘catch’, and other small disputes such as those who become indisciplined. They go and form their own groups and they return to fight us sometimes,” Sparko said.

At this point I’m exhausted from walking. Kalule tells Rato that we are exhausted. “Sparko, our visitors want to leave. Man-i, let’s go for a drink at kafunda,” he says. Sparko comes closer and shakes hands with us saying we ought to join them for a drink next time. It was 12.30am and we walked away taking every step with caution.

Drugs they use

Asked about what kind of drugs they take, they say anything they find alcoholic or any substance that can intoxicate them. The common ones in their camp are referred to by their slang names; marijuana (weed), heroin (embangu), cocaine (massada), amphetamines (Mr Issue), Cigarettes (Siga), petrol (finna) and methamphetamines (ekibaaba).

Intervention

Charles Ojok, the LC1 chairman of Kiwafu Zone in Kisugu, says the involvement of NGOs such as Gals Forum International in partnership with Plan International have stepped in to bring safety and shape many of the people’s mind-sets, including his.

“I have grown up knowing that some of our societies do not value girls but this has changed. We have involved our police and parents. The places of entertainment, lodges and the bodabodas also are a threat to the girls and we talk to them too. The Lost Boys are the other group we have involved and some of them are changing,” Ojok said.

The officer in charge of Kisugu Police Station, Joseph Kakooza, confirms the activities of the Lost Boys and says he has arrested a number of them, though they get back on the streets thereafter.

“I have arrested many of them and I have some of them in the cells. Some of them have changed but others have not. We shall continue with our work and we shall crack them down,” Kakooza says, adding, “these are not the only groups around. We have Katale boys, Ayebe, Malik and others.”

However Kakooza is quick to criticise the move by the president to remove the law against idle and disorderliness.

“Most of these boys are idle and they do not have jobs, if they do, they are casual labourers and at night they come back to the streets and cause mayhem to the population,” he says.

Esther Namboka, the executive director Gals Forum International, says they have talks with the Lost Boys and they are slowly changing into responsible citizens who are not out to harm but protect the girls in one way or another.

“Much as we talk to the girls, empower them to become more assertive and get them some skills which can help them earn a living, we are also talking to the gang groups. We have created a rapport with The Lost Boys and some of them are getting reformed. We have also talked to bar and lodge owners to be parental, so that they employ the girls and help them grow financially, not make them sex workers,” Namboka said.