Can President’s middle-income dream be achieved by 2020?

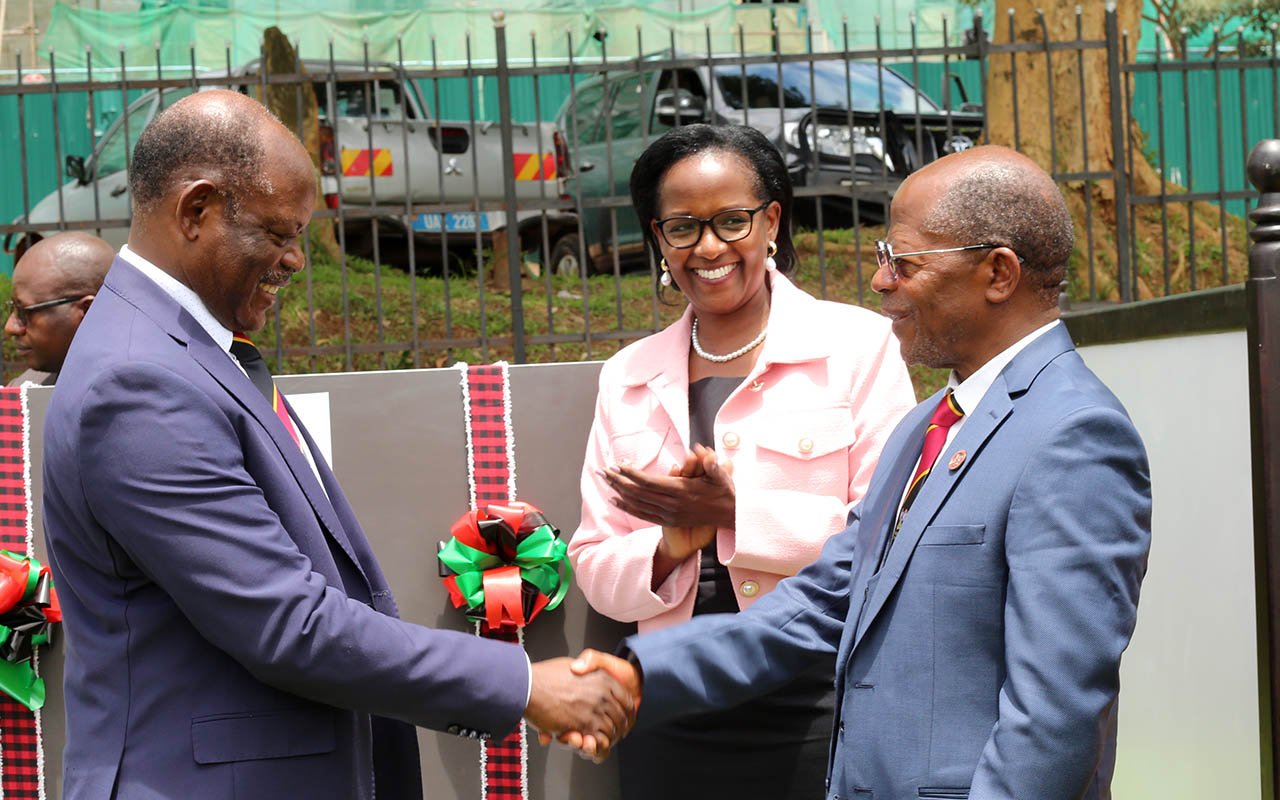

Chief Justice Bart Katureebe, President Museveni and Speaker of Parliament Rebecca Kadaga at the 2016 State-of-the-Nation address. File photo

What you need to know:

Uphill task. To achieve the near impossible feat, Mr Museveni promised to battle with the 68 per cent of homesteads that are still engaged in subsistence farming by emphasising the sale of fruits, micro-irrigation, using solar-powered water pumps and concentration on three main fruits, writes Solomon Arinaitwe

To pull off his flagship project of achieving a middle-income status by 2020, President Museveni used his inaugural State-of-the-Nation address in his fifth elective term to unveil a raft of five priority areas that he will put emphasis on turning around the economic fortunes of Uganda.

According to the World Bank, middle-income economies are those with a Gross National Income (GNI) per capita of more than $1,045(Shs3.5m) but less than $12,736(Shs42m). This is where Mr Museveni says Uganda will be in five years. In East Africa, Kenya is the only country with middle-income status.

To achieve this ambitious feat, Mr Museveni has promised to plug what he called “money haemorrhage” by attracting and incentivising investors to improve the local manufacturing industry and partner with EAC members to curb resource outflow.

Mr Museveni also vowed to fight corruption among the political leaders and the public servants and lashed at government officials that delay investment projects. Transforming Uganda to middle-income status by 2020 was Museveni’s campaign message and he repeated it when he claimed the out-going Cabinet “nearly took Uganda” to middle-income status.

Figures from the 2015/2016 National Development Plan (NDP), whose strategic goal is to transform Uganda to middle-income by 2020 with a per capita income of Shs3.4m, indicate that per capita income currently stands at $788 (Shs2.6m). This means every Uganda is earning Shs2.6m annually.

Poverty will have to be reduced from the current 19.7 per cent to 14.2 per cent, according to the National Development Plan. The NDP says this can be achieved through strengthening competitiveness for sustainable wealth creation, employment and inclusive growth.

Greeted with cynicism

But Museveni’s vows were greeted with cynicism, with many wondering whether a country with an average income of Shs2.7m will be able to turn it around to a minimum of Shs3.5m over the next five years.

For all the promises that Mr Museveni made, it was the promise to tackle corruption that was greeted with the most of cynicism. An inquiry into the Uganda National Roads Authority that discovered that at least Shs4 trillion was stolen by more than 90 officials is Mr Museveni’s new trump card.

He has vowed to hunt down those thieves – whom he called endangered species – with the fury of a muyekera (rebel). But with rough estimates that Uganda loses Shs510 billion in procurement related deals a year, Mr Museveni will be closely watched by sceptics who bet that his threats are empty rhetoric.

Ms Cissy Kagaba, the executive director of the Anti-Corruption Coalition Uganda (ACCU), a coalition of activists that track government corruption, says there is no need to be optimistic with Mr Museveni’s repeated vows to tackle graft.

“The President has been talking and talking [about fighting corruption] with very little action. He talked of ministers that ask favours from investors – that means he knows the people. Why are they still free? We cannot achieve middle-income status with corruption. What is supporting the regime is patronage and corruption and that’s why he can’t fight corruption,” Ms Kagaba says.

To achieve the near impossible feat, Mr Museveni promised to battle with the 68 per cent of the homesteads that are still engaged in subsistence farming by emphasising the sale of fruits, micro-irrigation, using solar-powered water pumps and concentration on three main fruits.

But questions still linger whether that will be enough to transform Uganda to middle-income by 2021.

Uganda’s economic prospects, according to the latest projection by the International Monetary Fund (IMF), are very bleak. The May 3 IMF economic outlook for sub-Saharan Africa indicated that economic growth for countries such as Uganda will be 3 per cent below the 6.2 per cent required to propel the country to middle-income status by 2020.

“After a prolonged period of strong economic growth, sub-Saharan Africa is set to experience a second difficult year as the region is hit by multiple shocks. Growth this year is expected to slow further to 3 per cent, well below the 6 per cent average over the last decade and barely above population growth,” IMF said in its economic outlook.

Prof Augustus Nuwagaba, an economic consultant who has worked with the Finance ministry, says transforming a country to middle-income status requires mainly three things; inculcating that vision into the whole population, financing and planning.

“You must have a buy in. Everyone in the country must be aware of the vision to transform to middle-income status. How many people have bought that idea and are willing to change their attitude towards the country and their attitude towards work?” Prof Nuwagaba says.

Prof Nuwagaba says for countries that rapidly transformed like South Korea, Malaysia and Mauritius, people were all working in that direction.

Government has clearly done little in the line of marketing Mr Museveni’s vision of transforming the country to middle-income status. Save for random mentions during the campaigns, there is no deliberate process of publicising the plan and making people work towards it.

Unrealistic

Dr Fred Muhumuza, an economist who has previously worked with Bank of Uganda, says the timeline of achieving middle-income by 2020 is “unrealistic” because even if the right “inputs” were put into the economy, they have to be given time to bear fruit.

On the policy front, the government has to do more to tackle the outflow of money and the high interest rates, says Dr Muhumuza, if investors are to be attracted.

“What is the government doing to lower interest rates? For interest rates to be lowered, the government has to scale down its appetite for money,” Dr Muhumuza says.

Mr Museveni acknowledged the problem of exorbitant interest rates during his address, proposing that the Uganda Development Bank (UDB) will be capitalised so that it gives low interest loans to agriculture and industry (manufacturing).

“Even when the inflation rate is 5 per cent, the banks lend at 23.5 per cent as of now. It is these commercial banks that are fuelling the craze of importing by giving endless loans to importers,” Mr Museveni said.

Mr Julius Mukunda, the coordinator of the Civil Society Budget Advocacy Group (CSBAG) says the ray of hope in Mr Museveni’s address was his promise to put an emphasis on the local manufacturing sector, which he says is achievable.

“You will never develop a country if you cannot protect your own industries and conform to the import substitution strategy. Why, for instance, do we have to import toothpicks and match boxes? It has come at the right time and it is achievable,” Mr Mukunda says.

To prop up the local manufacturing industry, government institutions like the army and police, which are some of the leading consumers, would buy locally made products.

The President said Uganda is currently “donating” to India, China, UAE, Japan, EU and USA a total of $5.528 billion (Shs18.5 trillion) per year. For this money, importation of textiles accounts for $888 million (Shs3 trillion), leather goods $0.22 million, fruit products $20.2 million (Shs67 billion) and second hand cars $568.7 million (Shs1.9 trillion).

But Mr Museveni did not tell us why the government is the leading importer, effectively shooting itself in the foot.

“If you look at the import data, government is a leading importer. And the imports will make the exchange rate higher and crowd out the private sector and no investor will come to a country with high interest rates no matter how good the roads are,” Dr Muhumuza, an economist, says.

Manufactured exports as a percentage of total exports currently stand at 5.8 per cent, and the goal of the National Development Plan is to increase them to 19 per cent.

The National Export Development Strategy (2015/16-2019/20), which was unveiled last year, encourages tax incentives to companies adding value to products, reducing administrative barriers to export of raw materials, government investment in value addition, quality assurance and assisting SMEs in the process of product certification.

Mr Mukunda says the ray of hope in Mr Museveni’s speech was his promise to put an emphasis on the local manufacturing sector, which he says is achievable.

But Mr Mukunda does not agree with Museveni on the policy of importing knock down cars to assemble cars from here. In his address, Museveni argued that importing a car in a knockdown state and is assembling it here is 25 per cent cheaper that importing an already used car.

But Mr Mukunda says Uganda does not have comparative advantage in importing cars and it should instead focus on sectors like agriculture.

“We do not have a comparative advantage in assembling cars; we should leave that to the Japanese. We have gorillas, Japan does not have them. We can plant our cereals which many countries cannot,” Mr Mukunda says.