Coup talk takes us back to Obote

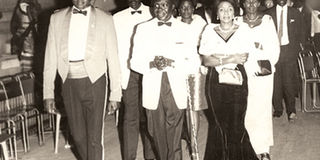

Idi Amin (L) and Milton Obote (2ndL) during their happy days. Amin as Chief of Defence Forces overthrew Obote’s regime. COURTESY PHOTO

The prospect of an openly military government running the country – as raised and then denied by a number of senior figures including the President himself - would only help clarify matters for the ordinary citizen, but complicate them for the regime.

The army has intervened in every election since 1995 on the side of the NRM.

Anyone in doubt should talk to those who experienced the military lockdown of Rubaga North as the police tried to help the NRM candidate steal the vote. Yet what we are effectively being told is that the military may have to overthrow its own party, in order to keep the party leaders in power.

Much as it is being presented as a statement of strength, it is actually a further indication of how difficult things have become for the ruling clique.

Given our rich history of military regimes, beginning with the 1888 coup against Kabaka Mwanga by the missionaries and their armed followers which degenerated into a civil war, we have plenty of examples from which to choose to understand the real meaning of this announcement.

Any such new government would resemble nothing more than the Obote I regime in both the way it came to power, and the way it went out.

In case anyone needs reminding, we should not forget that the 1966 coup was Obote’s action against a government of which he was a part in the form of the UPC –Kabaka Yekka alliance.

It came after a sustained period of Obote having difficulties with “stubborn” ministers and parliamentarians from within his own party as well as the coalition, some of whom ended up being detained under colonial era laws.

Just like today, the military actions of 1966 were explained as “necessary” to prevent a disaster.

This is where the real complication might be; having helped Obote to the presidency, the army helped consolidate the regime by maintaining the State of Emergency first in Buganda , and then in the rest of Uganda.

Again, for those not in memory of this, a “State of Emergency” is another (again) colonial era trick of dictatorial governance used to “legalize” detentions without trial; the suppressing of demonstrations; deportations; media censorship; and other such violations of basic freedoms in the name of security.

It also means denial of freedom of movement through the imposition of a dusk-to-dawn curfew on the population.

Once you have struck against a Constitution, is it logical to expect the people you worked with in that enterprise to then revert to respecting “authority” afterwards? This is what Obote –who was on his third Constitution (the Independence Constitution; the 1966 “pigeonhole” Constitution; and then the 1967 Republican one) by 1971 discovered, when his General, Idi Amin, who had spearheaded the 1966 military actions, then made his own move.

Under Obote, General Amin found that his army physically controlled the country but had little say in what the Big Man did with that control. This created its own tensions.

In fact, it is the root of the NRM’s current crisis: The NRM MPs have discovered that despite their overwhelming control of Parliament, they are not in charge of making laws on critical issues such as oil and corruption. It is their rebellion against this that has led to the coup threats.

This seems like a solution in the beginning, but it usually has another effect. Again like in the Obote I period.

The effect of such a coup would be to render formal civilian politicking redundant or even irrelevant (assuming it would be allowed to continue in the open).

This does not mean that the differences of political opinion disappear. Far from it. Instead, the political issues migrate to where power is now being mediated: the army. This is how Amin became a political figure, as well as a military one.

The reality today is that the country is run by a network of cronies and their families that stretches across the political, financial, security and business sectors. The army, as such, is only part of that.

If these unresolved debates migrate to the ranks of the new military government, for how long will such an army continue to do the Big Man’s bidding?

I have read comments about this matter that seem to place a lot of hope in the idea that the United States would not be happy with Uganda under direct military rule.

These seem to have been strengthened by the US Ambassador’s recent remarks on the subject. We should not fool ourselves.

The United States’ friendship with Uganda is built first and foremost with Uganda’s military and security institutions as opposed to the civilian ones.

Those are their real friends. What is more, the US has dealt with and deals with regimes that are already further down the path of naked despotism than the NRM has so far managed to travel.

If a new openly military regime is to be prevented, it will not be done by the Americans, but we ourselves.

We will just be at the beginning. Again.

The writer is a journalist