I paid the price for trying to run kadogo school effectively

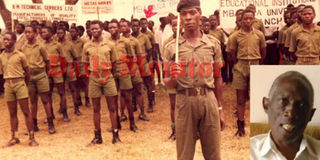

Former child soldiers on parade at the Kadogo school in Mbarara District in the late 80s. Capt Katimbo (inset), headed the school twice. PHOTOS COURTESY OF HENRY LUBEGA

I first admired [Yoweri] Museveni during the 1979 liberation war. My love for him was because of his numerous efforts to topple the [Idi] Amin regime. When he finally started a political party in 1980, I was more than eager to support him. I was a Grade Three teacher at the time.

During those elections, we canvased votes for Samson Kisekka [RIP] for the Busiiro North constituency but unfortunately, he was defeated. After the elections, Museveni went to the bush. I went to Bidandi Ssali’s place in Nakulabye for advice on what next now that our leader had gone to the bush.

He showed me a number of children and said, ‘Do you see those children? I want to see them grow. Don’t you have children?’

‘Yes,’ I told him and he said, ‘Go and raise your children. Stop asking where Museveni has gone.’

The person I had expected to advise me had instead discouraged me. So I went home and watched as the war escalated in the Luweero area, including Masulita my home area after the Kabamba Barracks attack.

There was heavy deployment around our area, cutting us off from other parts. Nevertheless, I would stealthily go to Kalongelo at the weekends to do Chaka Mchaka. Not so far away from my home area in Kakiri was a military roadblock manned by Tanzanian soldiers. It attracted the rebels.

The night before they attacked the roadblock, I got a strange visitor at my home at around 9pm. The visitor introduced himself as Kamwerere and said he had been sent by Mzee (Museveni) to call me. I asked myself what this Munyarwanda wanted from me.

At the time I was the deputy head teacher of Masulita Primary School. I had never met Museveni, but I suspected that it was Jacob Asiimwe who told him about me. Asiimwe and I were teaching at sister schools. Asiimwe taught at the secondary school while I taught at primary level.

After walking for about two miles in the forest, we got to where Museveni was. I went with my elder brother Nalumoso.

We found Museveni with Asiimwe and he asked, ‘Of these two, who is Katimbo?’

I identified myself and he asked whether the other person I had gone with could be trusted. I said yes.

Museveni then went on to say his boys were preparing for an operation but they were hungry. He wanted me to organise some food quickly. I went back to school and mobilised for food and after eating, they attacked the roadblock that night.

The next morning at around 10am, Kamwerere again came for me. This time Museveni and Asiimwe showed me the captured guns. Museveni pointed at the GPMG [General Purpose Machine Gun] and said, ‘With that the war is over.’

He went on to say, ‘The problem I have is that all the soldiers are tired. I need people to carry those guns. Go and organise boys you trust.’

He wanted 12 boys, but I took about 20; this was the first lot I sent to the bush.

The primary school was a government school with both boarding and day sections with a population of 1,200 pupils. However, as the situation worsened, children stopped coming to school. Those in the boarding section could not be picked by their parents. I was stuck with them.

When I decided to join the fighters full time, I mobilised some 16 teachers and about 60 pupils – most of them in P4 and P5. Some teachers feared to go with me to the bush.

For the children, I went with them because there was no way I could leave them at school unattended to. Their parents were unknown to me and I did not know how to find them.

In the bush, the very young ones were joined with girls from the secondary school and taken to Kijaguzo Parish and put under Fr Seguya’s protection.

He was a staunch NRA supporter. They stayed there until a time when they were older enough to join the fighting forces. The 16 teachers I went with joined the rebel ranks immediately.

Life in the bush

When I fully joined the fighters, I did not continue with training. It was the teachers who went for training while I started off work at the Resistance News Magazine. This was our newspaper and I worked on it with Roland Katunguka. He was the director.

We had a typewriter and along the way I went to Light College Katikamu where I got a cyclostyle which we used to print the magazine. How it found its way out of our territory, I never got to know.

I was later moved from the magazine to administrative officer in the Nkrumah unit. This was a mobile unit operating within the Lukola area. After sometime, I was sent for a basic course in Kasejere in Singo.

The training was done at Cardinal Nsubuga’s farm where there was a lot of food. It was a secluded place before the rebels went on to start the western axis.

Ndibalema was the course administrative officer while Ahmed Kashillingi was the course commandant. Before the end of the course, I was promoted. However, the promotion came at a cost.

Ndibalema called me one morning and told me to break down his house. It was a one-roomed big house thatched with banana fibres. He ordered me to pile all the debris on one side and reconstruct a new one. I was supposed to do all the work – breaking down the house, looking for material and reconstructing the new house – between 8am and 6pm all alone.

He went on to have people watch over me to make sure I did not solicit any external help. Not knowing what to do, I saluted him almost in tears as I went to start on the work.

Some six teachers who saw me before the administrators were concerned. They thought I had been discontinued from the course. I told them of the assignment ahead of me and they offered to go out of the camp and look for some construction materials.

I broke down the old house as they brought banana fibres and poles which they left outside the quarter guard. I managed to put up the new house and made two new chairs and a table.

At around 4pm, I went to the administrator and told him the house was finished. He instead cautioned me against playing games. But when he saw what I had done, he immediately announced my promotion.

After seeing the work, he told me, ‘From today you are a commissioned officer. You are a junior officer class two.’ That was an equivalent of a Lieutenant.

After training, I went back and continued with administrative work up to the time Kampala fell. I did not go into battle field as I was more into administration. My immediate boss Julius Chihanda never wanted me to go out of the base.

It was not until I joined the 9th Battalion, which was sent to Karamoja and commanded by Matayo Kyaligonza, that I went to the battle field.

In 1987 when the kadogo school was started, it was Kihanda, who was then at Republic House (currently Bulange), who advised the President to appoint me head of the school. Three messages were sent to the battalion commander then based in Mbale, but he did not want to release me.

It was until Museveni sent a fourth message warning Kyaligonza to either release me or go and take over my post that he let me go. At the time, being taken to head the kadogo school looked like a demotion.

Kyaligonza called me from Nabilatuk to Mbale where the headquarters were and told me of my new appointment. By then I was JO1, equivalent of a Captain. Kyaligonza told me to leave immediately for my new post.

Mbarara Kadogo school

When I got to the school, what I saw was disheartening. No one seemed to care at all; the children were living in a filthy environment.

The commandant I found feared to face them because they had guns. As soon as night fell, he would run to lock himself up. Some of the kadogo’s would at night get guns and go out to steal from the locals.

I started by putting aside military orders and instead looked at them as children. I wanted to rehabilitate them by first transforming them from a militant mentality.

The only way was not to use military orders because some of them had been in more battles than myself, or even the commandant I was replacing. I had to deal with them as a trained teacher and a parent. That was how I managed to deal with them.

Their rehabilitation and going back to school was funded by the United Nations and the children knew what kind of supplies they were getting.

But unfortunately, much of the supplies were left at Lyantonde and a small portion of it reached Mbarara. As a result, they never got enough food and were always hungry.

At my first assembly, I made sure they get a head prefect – Moses Dibya, a P7 pupil – and I told them from then on he was the commanding officer. He was to make sure no child slept out with a prostitute, as had been the case.

I also tasked him to ensure that no weapon was kept in the dormitories; all of them were collected and brought to me. I also assured them that if any of them was tired of school and wanted to return to their respective units, they could come for a release letter as long as they were 18 years and above.

I involved them in their own affairs. I made them get their own quartermaster; the one in charge of their food. This improved their welfare because the way the supplies were dispatched from Mbuya was the way they reached Mbarara.

By the time I joined, out of the 2,600 children, less than 200 attended classes. The rest would wonder around Mbarara Town and the surrounding areas looking for food.

From Mbarara to Nabisojo

When I instituted measures of ensuring that all the supplies reached the school, this got me enemies who worked for my departure from the school.

Early in 1989, I was transferred to Nabisojo in Luweero after the intervention of then army commander Salim Saleh. When the kadogo’s learnt of my transfer and the mistreatment that followed, they started waylaying President Museveni whenever he was travelling past the school.

They demanded for my return to the school. After three complaints from the kadogo’s, Museveni asked who transferred me from Mbarara. When he was told, he gave orders for me to be returned to the school with immediate effect.

I, however, set some conditions for my return to Mbarara. That was around late 1989.

The day I returned to the school, I found the kadogos waiting for me at the quarter guard. They pulled out the driver and one of them took over as the rest pushed my Land Rover all the way to my residency.

By 3pm, all of them had returned from the surrounding areas and town where they had escaped to. I stayed for some years until a one Kalisa masterminded my departure.

It was basically my developments at the school which cut out suppliers that was responsible for my enmity with those who did the procurement.

From Mbarara to retirement

After a fall out with some powers within the top echelons in the army, I was taken to Bombo Barracks in the artillery section.

Bombo had its own problems between the leadership and the ordinary soldiers. I stayed there for a while and was sent to the office of the chief of staff.

It was while there that I decided to retire from the army. Little did I know that the President never wanted me to retire. After several failed attempts, a friend called Semwezi helped me sign my retirement papers in 1994, for which he spent some months behind bars.

Since my retirement, I am happy that not everybody has forgotten me. The institution may have forgotten me, but a good number of individuals still remember me. Despite that, I don’t regret the decision I made in 1982 when I left my teaching job to join the rebels.”