‘Kiir, Machar should be punished for war crimes’

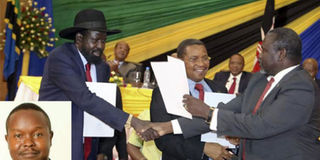

South Sudan president Salva Kiir (left) exchanges the SPLM Reunification Agreement with Dr Riek Machar (right) as former Tanzania president Jakaya Kikwete looks on in Arusha, Tanzania, in January last year. Inset is Dr Remember Miamingi who says that most of the people ruling South Sudan today deserve to be prison for the rest of their lives. COURTESY PHOTOS.

The guns are now silent and the former protagonists are together in a unity government. Is that the best case scenario for South Sudan in your opinion?

I want to say that anything that was designed to bring the suffering of the South Sudan people to an end by silencing the guns is a welcome development. Therefore, the formation of a transitional government of national unity is, and should be a step in the right direction.

However, my concern is that the transitional government of national unity is starting on a very difficult ground, and this is indicative of how long it took (for it to be formed after the agreement was reached).

The government was supposed to be constituted in November 26, 2015 and only weeks ago has it been constituted. The challenges that stopped the government from formation are the challenges right now that are beginning to frustrate the operations of this government.

So in as much as it is a step in the right direction, it is also probably a beginning of a new challenge for South Sudan. Also, the same individuals that were in the old government that fell apart, which killed, destroyed and raped the country, have finally been rewarded with the power.

Have they just been rewarded?

You know they hold power and it’s difficult to cede it.

I use the word ‘rewarded’ because these politicians literally took South Sudan hostage and it seems they demanded a ransom, which was their return to power. The ransom, the power that they killed and destroyed the country for, has been given back to them. That has a lot of implications for peace and stability in South Sudan.

But he who has power makes the rules most of the time.

The international system operates on the basis of minimum moral standards and those standards are codified in the international human rights treaty and the treaty dealing with international crimes. Even within the African Union and the region, we have the basic minimum standards that stipulate what happens to whoever is alleged to have committed crime of international nature.

You are calling for accountability here …

Absolutely, but that is a challenge. How do you expect a government now that has come together that has been alleged to have committed crimes of international proportions to preside over a problem, to preside over a mechanism designed to try and possibly convict them?

It is conceiving the impossible. Stability versus accountability is a big debate. Whoever is trying to bring about peace and stability in South Sudan is concerned about who, among the players, has the ability to stay there because the international community will eventually have to go away and South Sudanese have to govern themselves.

How do you reconcile stability and accountability in this case?

Peace and justice are interrelated and interdependent. To have peace, you need justice and to have genuine justice, you need peace. What, unfortunately, has been used by people who say you need peace in South Sudan is the presumption that you can have peace without justice.

Our history has proved that it is impossible. The only reason why any peace talks in South Sudan resulted into just a “commercial break,” like you say in the media, is that each of those peace discussions and accords lacked effective, efficient and meaningful accountability mechanisms.

So, the very people who committed war crimes in the 1980s were the same who were rewarded with government and power in 2005. And they are the same individuals who went into the habit when they lost power in 2013.

And trust me, because the government we have now cannot accommodate everybody, those who lost out in the government of national unity will go back and commit the same atrocities and distabilise and for the sake of stopping instability, we will reward them.

It becomes a vicious cycle of criminality, appeasement, insufficient appeasement and more criminality. To break that cycle, you need to ensure that you cannot kill and be alleged to have committed crime and be allowed to be closer to power until your name has been cleared. It is simple.

There is a view that you can’t achieve justice and accountability when majority of the people are still illiterate and largely ignorant.

You see, we live today in an era of global citizenship. We have suddenly realised that as a nation, as a community, we face interrelated challenges that can only be addressed jointly.

We have a situation in South Sudan where people have been taken hostage by a corrupt elite that has captured the instruments of the power of the State and have used those to enslave, dismantle, kill and destroy. The only opportunity these people can have to challenge this is only if they have access to that difficult power.

But power capture by an elite regarded as corrupt is not unique to South Sudan.

Absolutely, we have different challenges that manifest in different ways in different countries and those challenges should be tackled equally. But we have had 50 years of talking to each other through the barrel of the gun.

It is the only language that we understand and through that, we have had the concentration of power in the hands of men with arms. Poverty has become the new instrument of war in the country. We have just seen South Sudan destabilise Ethiopia. That has happened in Kenya, Uganda and other countries.

So we have a situation that is so critical and solving it is our responsibility as South Sudanese. But we need to move the peace and accountability agenda forward and to use South Sudan as an example. Why this problem has persisted is because it happened in the Central African Republic and nothing happened; it happened in Chad and nothing happened. If it happens in South Sudan and nothing happens, somebody here will be encouraged to do the same.

We are saying even though it is a global problem, we need to start tackling it from somewhere. And South Sudan presents a good opportunity. Let us make a statement as a continent that this cannot continue.

How can the international community intervene to make that happen?

One, we want the international community to move swiftly to put in place the hybrid court that is provided for in the peace agreement, with or without the support of the government. Secondly, war crime evidence in South Sudan is disappearing so fast.

We want the international community and the African Union to move swiftly to begin to preserve the evidence of crimes that have been committed in that country before the State organises itself and begins to destroy that evidence. We also want the international community not to just put structures in place but to put in place resources to ensure that these structures operate and do so effectively.

But we know that the ability of the international justice system to deliver national healing and reconciliation is limited.

And that is why the peace agreement provides for a national commission of healing and reconciliation. We want that mechanism to be the priority of the government, the priority of the African Union, the priority of the East African Community.

You raise a problematic issue there – punishing those who are responsible for crimes. In many cases, you will find that those responsible for crimes are also those with power…

Absolutely, if the law is to be of any use to a society, if those who steal goats are punished because the law is against stealing, a man who destroys a country and millions of lives has to be brought to justice if our belief in the law is to be strengthened. Secondly, note that powerful people will come together to obstruct justice. But they are only as powerful as they are in that country.

At the international level, we have seen very powerful people from Rwanda, the former Yugoslavia, the Ivory Coast, Liberia, that have been brought to a mechanism of justice. Where there is a determination at the regional level, a conviction at the international level that enough must be enough, local power will give way to accountability.

You name countries where rulers who committed crimes were punished. I can cite even more examples of countries where powerful people who committed crimes were actually not punished. International politics punishes and exonerates you depending on who your allies are …

That is absolutely true. Even within our national jurisdictions, ordinary thieves are punished; people who steal from the State are not punished.

But we have situations where both the ordinary thief and the thief at the national level have been punished. In the same way, the international system has its strengths and weaknesses. So we must push for the system to work for everyone.

And we cannot do that on a balance sheet – that because Americans were not punished in Afghanistan, so Riek Machar and Salva Kiir should not be punished in South Sudan. We can still punish these two and all the generals there who committed crimes as we continue to agitate that the Americans who committed crimes in Afghanistan be punished. We are dealing with the dreams, with the lives which have been destroyed by these people.

There are, for example, businesses that benefitted from the war in South Sudan. We need to put in place a mechanism to ensure that killing people and destroying livelihoods is expensive to the perpetrators.

And until we start working on this and start with it in South Sudan, there will be more cases of the same abuses down the line and people will start citing South Sudan as an example – it happened in South Sudan. There has to be somewhere to start and I have to say that if there is any classical case to start with, it is South Sudan. The kind of killing that has taken place in Sudan has taken place in broad daylight, in crude and primitive ways.

There is raw evidence. The killing that took place is very well documented. So we have soft targets, so to say, to start demonstrating that there is an African solution to African problems that can look into the eyes of power. We have solidarity in crime on the continent – that is in abundance – but we want to build a new solidarity for accountability, for justice, and for healing. And that can start with South Sudan.

You have dwelt a lot on the role of the international community. But South Sudanese are the most important stakeholders in all this. Have they been mobilised?

Millions of South Sudan citizens in and outside the country are talking every single day, and they are calling for action on the side of the government, and they are calling for action on the side of the international community. And we have people who always go to State House asking and calling on the government to account. These people are not powerless, they are not victims; they are actors. But they are actors that have been paralysed by the special context of the country where there are no infrastructure to mobilise, there are no social networks to build on. They were all destroyed. This is a country that is operating on the basis of force. Journalists and others are killed. We are saying if you created and put in place a mechanism for accountability, it is South Sudanese who will come out and testify. So we want civil society to be facilitated, to be mobilised, to be the driver. But they can only do that in an environment where they are protected.

Experiences in Kenya and Zimbabwe suggest incumbents use transitional governments to strengthen themselves. Don’t you envisage the same danger in South Sudan?

Absolutely, that is a danger. But there is a slight difference. In Kenya and Zimbabwe, you were talking about two different parties, which in each case had come together in coalitions. In South Sudan, we are talking about three pieces of the same party that have since been brought back together - The SPLM-In Government, the SPLM-In Opposition and the SPLM-DC. As long as there is power available to each of these groups, as long as they have access to resources, they will stick together. The only fear is when any of those groups loses power, because these groups fight not because of strategy or anything else but power.

Nelson Mandela kept urging leaders to make compromises necessary for peace…

Absolutely, compromise is a day-to-day reality for everyone. But if the basis of that compromise is self-aggrandisement, self-enrichment, then that compromise is devoid of meaning. Why did we have to first kill 70,000 people before we made that compromise? It was because the formula of power sharing had not been agreed upon. Who were those involved in the power play? The same people. So we have here bad compromise, bad intention, bad timing.