Martyrs: Prof. Lunyiigo turns tables on colonial historians

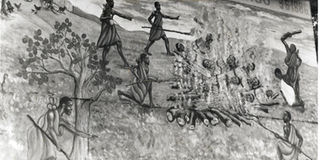

An artistic illustration showing the Uganda Martyrs who were murdered in Namugongo in 1886 by the then King of Buganda after they refused to denounce Christianity.

What you need to know:

The history professor observes that the burning of the martyrs was a political rather than a religious execution.

Whether you agree with him or not, history Professor Samwiri Lwanga Lunyiigo is convinced that Kabaka Mwanga II of Buganda killed the Christian martyrs at Namugongo not because he hated religion but because they were collaborating with the European missionaries and spying on him.

The missionaries, who, in turn, were collaborating with the prospective colonial administrators, would pass on the information to the colonial powers.

He observes that the burning of the martyrs was a political rather than a religious execution because if that was not so, missionaries like Mackay who claimed they had come to introduce religion in this part of the world would have led by example and offered to die with the Ugandan martyrs. That way, they would have equally attained martyrdom for their sacrifice.

I have not been to Whitehall, Canterbury or Rome for some time, but Lwanga Lunyiigo’s fresh interpretation of the history of Uganda under colonialism and the divide and rule role that was played by the missionaries in collaboration with the administrators to weaken the powers of the traditional rulers will undoubtedly shake the politicians and the religious leaders out there and indeed in other parts of the world.

Assertion

Prof. Lunyiigo asserts that, unlike any of his predecessors, Mwanga II was a real nationalist. But his role in resisting British colonialism was suppressed by European missionaries and other colonial agents who have continued to distort the history of Uganda to suit the interests of the colonial powers. Such bogus ‘historians’ have convinced the indigenous Ugandans and other historians the world over to pursue their line of thinking and hence continue to distort and portray the history of our country in a manner that justifies the actions of the colonialists.

In Lunyiigo’s book, ‘Mwanga II – Resistance to Imposition of British Colonial Rule in Buganda 1884 – 1899’, which was launched in Kampala on September 14, 2012, the professor states that the so-called ‘Readers’ were Mwanga’s pegs at the Palace who became insolent and started acting as spies for the European missionaries. Mwanga decided to punish them, and some were burnt on pyres at Namugongo. Since those who survived the fires, men like Apolo Kaggwa, Henry Nyonyintono and Fundi Kisuule, were appointed to very senior positions in Mwanga’s ensuing administration, Professor Lwanga concludes that the young ‘Readers’ were killed for political rather than religious reasons.

One of the other intriguing episodes in Prof. Lunyiigo’s book is about the alleged ‘traditional enmity’ between Buganda and Bunyoro. During the imposition of colonial rule, Omukama Kabalega of Bunyoro had a large army, and so did Mwanga II of Buganda. Both armies recruited fighters from various parts of Uganda into their ranks, deployed them separately against the colonial army but never confronted their common enemy as a joint force.

“That was an important lost opportunity”, the Professor stated at the launch of the book. “Because if the two armies had fought as a combined force they would have defeated the colonialists and enabled Kabalega and Mwanga to create one Uganda”. Eventually, Kabalega and Mwanga II were defeated, captured in Lango and sent into exile, first at Kismayu in Somalia, and later in the Seychelles where Mwanga died.

Lunyiigo explained that despite their failure to form a combined army, the two leaders collaborated in resisting colonial rule. That, among other things, shows that the much hyped ‘enmity’ between Bunyoro and Buganda is a ‘myth’, he added.