Population explosion forces Bakiga to migrate to Ankole, Tooro

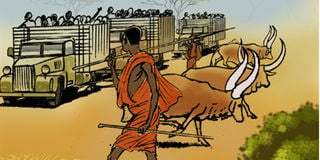

An illustration of Bakiga arriving in Ankole in government-hired lorries in July 1946. ILLUSTRATION BY DANNY BARONGO

In western Uganda, particularly Kigezi, the name Paul Ngorogoza rings loudest among the Bakiga. Ngorogoza was born around 1897 in Kabale, south Kigezi. He did not have formal education other than the catechism lessons conducted by the White Fathers. But he was very intelligent.

In 1946, he was made the secretary general of Kigezi District. In 1956, he was appointed chief judge of Kigezi sub-region. When he retired in 1960, he wrote a book titled Kigezi Nabantu Bamwo which was in 1969 translated into English under the title Kigezi and Its People.

In the book, Ngorogoza reveals how he, Mukombe and British colonial administrators were the architects of the 1946 Bakiga voluntary resettlement scheme.

By the end of World War I in 1918, it was obvious that Kabale’s population would soon explode. By 1930, the demographic situation was fast approaching bursting point. Immediately after World War II, resettlement of the Bakiga outside Kabale started.

The factors for this population explosion had been building up gradually but it was escalated by an external migration.

In 1930, there was an influx of refugees from Rwanda who settled in and around Kabale. The first Rwandan refugees had arrived in 1927. In 1928, the numbers of refugees surged. They were fleeing famine and also the insurgency caused by Semaraso Ndugutse.

Ndugutse was a radical. He lived in Byumba district north of Rwanda and he resented the Belgian colonial rule. He claimed he was Umwami (king) in Rwanda and rallied people to attack sub-county headquarters in the Byumba district. The colonial government sent forces to fight the attackers. Many of Ndugutse’s supporters were captured but others fled to Kabale inside Uganda.

Writing about the Banyarwanda fleeing into Uganda, on page 74 of his book, Ngorogoza states: “Most of these people who fled to Kigezi were Bakiga to the core and were, therefore, helped and protected by their fellow tribesmen.”

Because of that bond, they were allowed to freely settle in Ndorwa and Rukiga counties in Kigezi District.

Local chiefs in the areas also encouraged more people to settle in their territories because, then, people paid gifts and cash to chiefs. So the more the people, the more the chief would earn in gifts and cash.

By early 1940’s, south Kigezi had reached population explosion and scramble for land erupted.

Commenting on the land issue on page 80 of the book, Ngorogoza says: “A person would simply jump into his friend’s field and sow seeds after cultivating it saying, ‘even if I lose the case I will get the yield from this field.” Such was the magnitude of land problem in Kabale.

On realising the dangers, according to Ngorogoza, Mukombe, another prominent Mukiga, proposed to Mr L. A. Mathias, a British administrator who was the Kigezi District Commissioner (DC), that people be relocated from densely populated areas within Kabale.

However, when Mukombe and Ngorogoza met the DC, he told them that government had already planned for voluntary resettlement, but outside Kabale.

After further consultation, the DC called in experts from Kampala who included a British agriculturalist, J. W. Purseglove and two others. They were put on a team headed by Mathias to go and search for virgin lands to resettle the Bakiga outside Kabale.

In his book Ngorogoza narrates that they left Kabale on February 15, 1945, and headed to the north, Rujumbura County now in Rukungiri District.

“During our journey we passed via Rujumbura, proceeded beyond Rushasha and finally to Bugangari. We found the place teeming with wild animals such as elephants, and rhinos which drove away the inhabitants, so we were told. That day, we inspected the part of Bugangari and spent the night there,” he states.

The following day the team visited Kazindiro, Nkorongyero valley, Nyakariro, Rwerere and reached Nyakagyeme headquarters which is near the residence of now Maj Gen Jim Muhwezi, former Member of Parliament for Rujumbura County.

The day after, February 18, the team went to Nyakyera in now Ruhinda Sub-county at the boundary of Mpororo and Ankole. On February 19, the Ngorogoza-Mukombe team left Kebisoni via Buyanja and crossed River Kahengye at the Mpororo-Ankole border and proceeded to Kajara in Rwampara.

On February 22, they met the Omugabe of Ankole (king of Ankole) who accepted the resettlement of the Bakiga in his kingdom.

Bakiga move to Rukungiri

In 1946, government resettlement of the Bakiga into present-day Rukungiri and Kanungu districts started.

Ngorogoza wrote that on June 8, 1946, at least 100 people led by chief Mukombe set off for Rujumbura County from Kabale intending to resettle in Kinkiizi County in current Kanungu District. Some of the migrants obtained virgin land in Rujumbura and therefore did not proceed to Kanungu.

Ngorogoza says at least 52 men got land in Buyanja, Ruhinda and Nyakagyeme sub-counties.

Meanwhile, Mukombe and others continued to Kinkiizi and obtained land in the sub-counties of Kambuga and Kirima in Kanungu.

Kihiihi, in Kinkiizi became the Bakiga’s newfound land. In Kabale, a special committee of former sub-county chiefs was appointed to supervise the resettlement of the new immigrants in north Kigezi, Ankole and Tooro kingdoms.

The former sub-county chiefs were preferred because they were personally known to Ngorogoza and more knowledgeable about the community than others.

Speaking to Sunday Monitor recently at his home in Kabale Town, 91-year-old Kigezi historian Festo Karwemera spoke about the Bakiga resettlement. He remembers one of the officials involved in resettling the Bakiga was a sub-county chief called Ephraim Mbareba.

Ngorogoza states in his book that one Samuel Kayongwe, who had been a sub-county chief in Kabale, was appointed the chief of Kambuga Sub-county and entrusted with resettlement of the Bakiga in Kihiihi, Kanungu near the Uganda-DR Congo border.

Kihiihi, which was previously known as “Rwanga-Minyeeto” meaning “an area hostile to children” because of the high mortality rates among children due to malaria and other infant diseases, was renamed “Rukiga-Ensya” meaning “new Rukiga”.

It was after some time that that name was also changed to Kihiihi as we know it today.

Government report on settlement

More literature about the Bakiga resettlement is found in the colonial government annual report “Planned Resettlement in North Kigezi” published in the Uganda Official Bulletin, Volume 9, No. 10 of October 1958. It was authored by Mr K. S. Ferguson, the assistance District Commissioner of Kigezi District.

“Resettlement from south to north Kigezi was started as an assisted government scheme in 1946 and since then nearly 30,000 people have been moved,” the report states.

About the locality and size of the new settlement areas, Ferguson wrote: “This is an area of approximately 20 square mile, three miles from Buffalo Lodge and five miles from the new Congo road. The soil is a light sandy loam.”

“The country is intersected by thickly wooded valleys, many of which contain small perennial streams or pools. The rainfall is about 45 inches per year. The area is adjacent to the southern end of the Kigezi Game Reserve [Maramagambo forest] and there were many elephant and buffalo” Ferguson stated in his report.

Kihiihi and the adjacent areas indeed were not for human settlement but wild animals and indeed Ferguson described it thus: “Animals from the plains such as Kob and Topi kept to the short grass area nearer the Congo road which is unsuitable for settlement.

There were scattered settlements of the Banyabutumbi tribe, remnants of the considerable population which was driven out by the game and fever 35 ago.”

Settling the Bakiga in north Kigezi was slow but by March 1957, a great deal of work had been done in clearing the area for settlement.

There were 18 miles of access tracks [roads] and 41 protected springs constructed around the area by the government which encouraged more people to migrate from Kabale to Kihiihi in particular.

“From August 1957 to February 1958, settlers moved in steadily and there are now 180 families of 789 people in the Kihihi area. In February, however, many fell sick with malaria which frightened off prospective settlers,” the Ferguson report indicated.

However, he said a game guard and a nursing orderly had been recruited and a main camp erected.

“A nursing sister visits the aid post fortnightly and the district medical officer and the district health inspector frequently. But malaria is endemic, though few mosquitoes are seen,” Ferguson says in his report.

Having reaped from the economic effect of cheap labour from the new settlers, the colonial government decided to acquire more land from the game park for the settlers.

The Ferguson report said of the plan to acquire more land: “The proposed alterations to the Queen Elisabeth Park boundary and the release of part of the game reserve will mean that a total of approximately 40 square miles is still available for settlement.”

“Of this, areas at Kaniabizo near river Ntungwe and at Bwambara in Rujumbura have been prepared for settlement by making of the further 16 miles of tracks and 49 protected springs. Settlers are now beginning to move in.”

Probably owing to the economic prospects foreseen by the British colonialists in conjunction with the World Health Organisation, in early 1959 DDT was for the first time sprayed in Kigezi sub-region in order to eradicate the malaria epidemic.

With enough free land, Bakiga started off in high gear as cultivators. Soon, every home had large coffee and tobacco farms supplying the tobacco factory earlier established near Bugangari headquarters now in Rukungiri District.

Later, because of fertile soils and enough labour, a tea factory was established at Kayonza, now in Kanungu District.

Writing about the settlement of the Bakiga in Bugangari in Rukungiri, Ferguson wrote: “But it is certain that the settlement can make a considerable contribution to production. Kigezi [tobacco] Industries Limited has a flue-cure tobacco factory at Bugangari.

It provides Rhodesian seeds, tends nurseries from which seedlings are distributed to local farmers and buys and cures the crop. This crop has produced more in excise duty [revenue] in four years than the cost of resettlement.”

Bakiga migrate to Ankole

On July 19 and 20, 1946, Bakiga chiefs met with Ankole leaders at Kichwamba sub-county headquarters in Rujumbura in Rukungiri to formalise the modalities of the Bakiga resettlement in Ankole.

Thereafter, people on government-hired lorries started arriving and settling in Kati, Bukari, Kashenshero, Bigodi and the areas neighbouring the Imaramagambo forest and in Bunyaruguru in southwest Ankole.

Others were resettled in the south and central Ankole in Rwampara, Sheema, Kashari, Rubaya and Rubindi in the former Ankole kingdom.

After Bakiga had acquired new settlements in Ankole, the secretary general of Kigezi District Council, Ngorogoza was delighted.

On page 95 of his book he wrote: “Kigezi should be grateful to Ankole for allowing us possession of such valuable land. On the other hand, Ankole also benefited by getting new blood into their country that enriched Ankole through commerce, cash crops, taxation and so on, and thus boost the development of Ankole.”

Going to Tooro

In a few years, the Bakiga had filled the areas given to them in Ankole. It once again became obvious that another “new Rukiga” was needed elsewhere and beyond Ankole.

The Bakiga in the Ankole reached to their senior elders and relatives back in Kabale. In June 1955, the Kabale District Council sent a delegation to meet Omukama of Tooro (king of Tooro) to allow them settle in his kingdom. Their request was accepted.

The king allowed the Bakiga delegation to inspect the areas of Kibaale, Kiziba, Namwegyenda and Dura. They were impressed.

Shortly after the Omukama of Tooro accepted the Kabale delegation’s request, the Bakiga settlers started arriving, but Ngorogoza cautioned them. His counsel is contained in his book.

“I would, in writing this, like to remind the settlers that even if they become rich and change their mother tongue, they should remember the proverb ‘even the [hot] water eventually cools’. They must never forget the good customs and characteristic of the Bakiga, nor forget their language; and they must feel in their bones that they are Bakiga, remembering where they used to live.”

Migration to Ankole, Tooro

On July 19 and 20, 1946, Bakiga chiefs met with Ankole leaders at Kichwamba Sub-county headquarters in Rujumbura in Rukungiri to formalise the modalities of the Bakiga resettlement in Ankole.

Thereafter, people on government-hired lorries started arriving and settling in Kati, Bukari, Kashenshero, Bigodi and the areas neighbouring the Imaramagambo forest and in Bunyaruguru in southwest Ankole.

Others were resettled in the south and central Ankole in Rwampara, Sheema, Kashari, Rubaya and Rubindi in the former Ankole kingdom.

Move to Tooro

In a few years, the Bakiga had filled the areas given to them in Ankole. It once again became obvious that another “new Rukiga” was needed elsewhere and beyond Ankole.

The Bakiga in the Ankole reached to their senior elders and relatives back in Kabale. In June 1955, the Kabale District Council sent a delegation to meet Omukama of Tooro (king of Tooro) to allow them settle in his kingdom. Their request was accepted.

The king allowed the Bakiga delegation to inspect the areas of Kibaale, Kiziba, Namwegyenda and Dura. They were impressed.

Shortly after the Omukama of Tooro accepted the Kabale delegation’s request, the Bakiga settlers started arriving, but Ngorogoza cautioned them. His counsel is contained in his book.

Next week read about how former president Idi Amin tried to resettle the Bakiga in Karamoja sub-region