White man’s cabbages save starving Bakiga from death

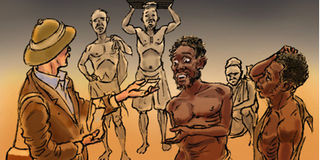

An illustration of British agriculturalist J. W. Purseglove. He was in charge of distribution of cabbage seeds to the Bakiga. ILLUSTRATION BY DANNY BARONGO

In 1943, heavy rains struck south-western Uganda and caused devastating soil erosions in Kabale in south Kigezi sub-region.

The rains skinned the hills and left them bare. They washed away the top fertile layer of the hills down to the valleys. The following year 1944, terraces, which have since become a trademark of Kabale, were introduced to prevent further soil erosion.

Today, besides the cold weather, Kabale’s terraced hills have made the district popular both in and outside Uganda.

The terraces lying calmly like contours on the undulating hills give Kabale an irresistible sight, especially for first-time travellers.

You can hardly take your eyes off the terraces as your safari vehicle ascends and descends the twisty steep hills of Kabale, a place that British under-secretary for colonies Winston Churchill in 1907 described as the “Switzerland of Africa” because of its chilly weather and rolling hills.

Only in Switzerland had he seen such a beautiful place before. Kabale is also famous for growing Irish potatoes. In the good old days when union and cooperative societies in Uganda reigned supreme for farmers in the 1950’s and 1980’s, Kabale was second to none in growing Irish potatoes and vegetables, especially carrots and cabbages.

The lucrative vegetable growing in Kabale made former Ugandan president Idi Amin so proud that at one time he satirically asked then British prime minister Edward Heath to send a plane to pick a truckload of vegetables and wheat donated by Bakiga in Kabale.

On January 22, 1974, speaking to a crowd at Kabale District headquarters, Amin said: “You will recall that following the launching of the ‘Save Britain Charity Fund’ on the December 14 last year [1973], the people of Uganda have responded very favourably,” Amin told the crowd and continued:

“The Fund was set up in order to help our brothers and sisters in Britain out of their present economic chaos. The response has been so good that the people of Kigezi District donated one lorry of vegetables and wheat.”

Amin then urgently requested for quicker means of transport to deliver the vegetables to Britain.

“I am requesting you [British prime minister] to send an aircraft to collect this donation urgently before it goes bad. I could have sent the donation directly, but as we do not at the moment have facilities for doing so, I hope you will react quickly so as not to discourage Ugandans from donating more,” Amin said in a remark directed at Heath.

The coming of cabbages to Kabale

Perhaps Amin knew the history of cabbage growing in Kabale and how the vegetable had earlier saved the Bakiga from starvation. Probably it’s the reason he wanted to send the plane-load of vegetables to save the British from a similar fate.

Cabbages were first introduced in Kabale by the British colonial administration in 1943 at the height of the famine. While cabbages are today widely grown in Kabale as a source of food and income, in 1943 it was brought to save lives of the starving Bakiga.

So one can courteously say, it was famine that inspired cabbage growing in Kabale. The famine had been occasioned by adverse effects of the World War II which coupled with a prolonged drought and stormy rains, left crops and homes in ruins and produced one of the most devastating calamities in the history of Kigezi.

In 1939, most young able-bodied men left to fight alongside the British forces in the World War II, leaving behind the elderly and children who could not cultivate enough food.

Towards the end of 1943 when the war was still raging, the Bakiga at home started starving. The colonial government in Kampala sent a British agriculturalist J.W. Purseglove, who had worked in Switzerland, to Kabale to save the desperate situation.

Purseglove was in charge of distribution of cabbage seeds to the Bakiga who eagerly planted them. They had never seen cabbages before. Nevertheless they planted the seeds. Helped by the fertile soils, within one month the cabbages had reached harvestable level. Under pressure of hunger, the Bakiga could not wait for full maturity. They started harvesting the cabbages.

The cabbages were the only food available for about two months before the government procured rice, maize and maize flour (posho) for the Bakiga. The cabbages became the sauce for posho and rice.

Having saved the starving lives by providing quick growing cabbages, the government moved on to prevent repeat of soil erosion, which had partly contributed to the ruinous famine.

Purseglove who had studied the invincibility of terraces in preventing soil erosion in Switzerland, introduced them in Kabale.

Kigezi elder and historian Festo Karwemera, born in 1925, vividly remembers the 1943 famine. At his home in Kabale Town recently, Karwemera spoke to Sunday Monitor about the horrifying memories of the 1943 famine.

“It was called enjara ya karyamiti” meaning “the famine that impelled people to feed on trees.” People ate shrubs and tree leaves to survive.

“I remember I was a young man and there was no food. Purseglove brought cabbage seeds and we planted them and soon we were eating them. We ate them [cabbages] for lunch and supper. I remember, because we had never eaten them, they were tasteless and also caused us diarrhoea.”

Karwemera added: “But they were better than nothing. We would put in a lot of salt to get some taste.” Karwemera is a local Mukiga author who has done several writings on the history of Kigezi.

During the interview, he also clarified that the word Kigezi should be written as Kigyezi, but because the British first miswrote it as Kigezi, people have adopted the corrupted version in the same way how the name Nkore was changed to Ankole, the area comprising the present day Greater Mbarara, Greater Bushenyi, Ntungamo and Isingiro-Bukanga.

Previous famines in Kabale

The 1943 famine was not the first. The earliest recorded famine in Kabale happened in 1897. However, this famine was more than a Kabale calamity. It was a national catastrophe, affecting all parts of the country.

It was caused by masses of locusts which had invaded and destroyed plants and trees across the country. It is recorded to have hit Buganda, Busoga, Bukedi, northern and western regions. It forced people in the north and north-eastern regions, including Bugisu, to feed on birds and bats to survive.

In Budama area people ate rats, squirrels and other small wild animals. In Buganda, people survived on fish, especially from Lake Victoria, while in western Uganda, the population survived on smoked meat of dead livestock that had starved or wild game meat.

The locusts ate almost every existing green plant. The 1897 famine was so devastating that at one point, the British colonialists contemplated abandoning Uganda and return home as the economy threatened to crumble.

This is recorded, though mildly, in a book: The Uganda Company Ltd -The First Fifty Years published in 1953.

In Kabale this famine is known as “Enjara ya Rwaranda.” There is no vernacular explanation why it was called “Enjara ya Rwaranda”.

Seven years later, in 1904, another famine struck Kabale. This one was referred to as “Enjara ya Mishorongo” meaning the “Mishorongo famine.” This too has no local explanation why it was called so.

But some authors have said the Mishorongo famine was an extension of the Rwaranda famine.

In a Catholic monthly publication, Musizi, in 1959, Yowana Kitagaana, a Catholic catechist, said Rwaranda had so devastated Kabale that some parents exchanged their children for food.

Kitagaana was a priest from Ssese Islands on Lake Victoria who arrived in Kabale with the White Fathers in 1903.

In Kabale, the situation had been escalated by the nearly 30 years of fighting between Batwa and Bakiga. Thus, Rwaranda owed its genesis to the 1873- 1901/2 Batwa-Bakiga war for supremacy, which claimed many lives. Bakiga are the fifth largest tribe in Uganda with 2.3 million people according to current population census figures.

Next Sunday read about why the Bakiga were resettled in Ankole and Tooro