Mwanga lights fires on martyrs as imperialist vultures hover

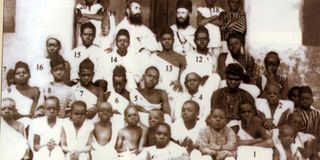

Some of the Uganda (Catholic) Martyrs before their death in 1886. The photo was taken on October 1885 when they had gone to the Bukumbi Mission in Mwanza, northern Tanganyika, to welcome and congratulate the newly-appointed Catholic Bishop, Monsignor Leon Livinhac.

What you need to know:

After failing to play the factions against each other, Kabaka Mwanga turns to violence to protect his kingdom but events in faraway lands were conspiring against the order of things.

Part V: The Making of Uganda

Kampala

When Mwanga succeeded his father, Mutesa I, as Kabaka of Buganda, he inherited a poisoned chalice. Although Mutesa had played the Muslims, the Catholics and the Protestants against each other, he had not resolved the underlying issue; that the new religions paid allegiance to an authority that claimed to be higher than the Kabaka and which had the backing of strong, foreign and ambitious powers.

Every convert to the new religions represented a subject who, at the very least, had a new master to serve other than the Kabaka or who offered divided loyalty.

The Kabaka had not been revered as a god previously but he at least had supreme authority and the power of life and death over his subjects.

An ailing and frustrated Mutesa had ordered the executions of so many converts that in 1882, the Catholic White Fathers left Buganda after only three and a half years and retreated to neighbouring missions in Tanganyika. The Protestants also weighed their options.

When he came to power in 1884 following the death of his father, Mwanga, then barely out of his teenage years, could have entrenched his power by expelling the Protestants and the Muslims but he was interested in the gifts that they continued to offer on one hand and, on the other, concerned about the reaction from the imperial powers behind them.

Instead, one of Mwanga’s early actions as Kabaka was to invite back the Catholics as he sought to continue his father’s politicking. The honeymoon did not last long, however.

Within two months of his ascent to the throne, Mwanga denounced all the foreign religions as dangerous and destructive to Buganda and threatened to exterminate all Muslims and Christians. Alexander Mackay, the most influential missionary and two of his fellow Protestant preachers were seized and three Baganda converts roasted to their deaths.

The plumes of smoke from the pyre were mere whiffs compared to the dark storm clouds that were gathering in the kingdom.

On October 29, 1885, Bishop James Hannington was seized and murdered in Busoga on Mwanga’s orders. Mwanga and his father, had before believed that foreigners who visited Buganda via the eastern route through Busoga, would bring about destruction to the kingdom.

Mackay sent word to Hannington to alter his route and arrive via the south but the warning went unheeded. Hannington’s religious rank did not help matters, either, arriving as he did in the midst of attacks on converts.

Seeking an advantage over their religious rivals, some of the Muslim Arab traders in Mwanga’s court encouraged the Kabaka to execute the bishop.

Between 1885 and 1887, over 45 pages, many of whom had served at Mwanga’s court, were executed or burnt alive for refusing to denounce the foreign religions they had converted to. In one instance, in May 1886, over 20 were burnt on one giant pyre in Namugongo; they would go on to earn worldwide recognition as the Uganda Martyrs whose courage is remembered every March 3.

By June 1886, only two Protestant and two Catholic missionaries were left in Uganda. Mackay tried to leave in August alongside Robert Ashe but Mwanga denied him permission, effectively keeping him hostage until July 1887 when Mwanga, in a flip-flop reminiscent of his father, suddenly warmed up the to missionaries and encouraged them to resume their preaching.

Bunyoro calling

Amidst all the regime change and bloodletting in Buganda, archrival Bunyoro was going through some changes itself. Led by Omukama Kabalega, Bunyoro’s forces had earlier defeated an Egyptian sponsored military expedition led by Samuel Baker, which had tried to raise the Egyptian flag over Bunyoro.

General Gordon, who had by now replaced Samuel Baker as governor of the Equatorial Province, had had his mind poisoned by the latter’s self-serving accounts of Bunyoro’s treachery and continued to unilaterally build forts in northern Bunyoro.

Kabalega had continued to fortify his kingdom’s position. In 1875, he attacked and defeated the army in the breakaway Toro Kingdom, reuniting it to Bunyoro.

Kabalega would, in probability, have gone on to attack the Egyptian forces if it hadn’t been for the appointment of Emin Pasha as the Governor General of Equatorial Province to replace Gordon.

Emin Pasha, perhaps wisely, adopted a more pacifist attitude towards Kabalega. He withdrew from Bunyoro to concentrate on trying to wrest the West Nile region from Arab slave traders but the Mahdist rebellion in South Sudan in 1883 left Emin Pasha cut off from his Egyptian masters. When he withdrew with his troops to the East African coast in 1889, it marked the end of efforts to colonise Uganda from the north.

What it did not end was European interest in colonising Africa. The threat of colonisation remained through the southern route via Tanganyika or the eastern route through what would become Kenya.

History was thus juxtaposed: Bunyoro under Kabalega had, thus far, successfully resisted foreign influences and attempts to colonise it.

Buganda, on the other hand, had been happy to trade with the Arabs and, under Mutesa, invite the “white man” to visit but was now struggling to cope with the competing influences of the religious groups.

Would Buganda have successfully resisted foreign influence if it had remained hostile to foreigners including the early explorers? Would Buganda’s resistance have encouraged Bunyoro to cooperate with the Egyptian-led forces and seek a military advantage over its archrival? How would the history of Uganda have appeared if the foreign influences had settled in Bunyoro before Buganda? Would, for instance, the country be called Unyoro instead of Uganda? Would the capital city be in Masindi and not Kampala?

We can only speculate but we will never know the answers to those questions. What we know is that back in Buganda, although natives continued to come forth for secret baptisms, Mwanga’s brutal execution of the martyrs had greatly alarmed the missionaries.

The three religious groups might have chosen to wait out Mwanga had they not learnt, at the start of 1888, of a plot by the Kabaka to exterminate them all. Two events then came together to change the course of history in the region.

The first event had occurred a couple of years earlier, in 1884, when European powers met in Berlin, Germany, to agree on how to share the continent amongst themselves. The decisions taken there would lead to the introduction of colonialism to Africa as well as the western concept of a nation-state that Uganda continues to try and understand today.

African territories were unilaterally cut up and divided by representatives of the European powers by simply drawing up lines on a map. The area comprising Buganda and Bunyoro fell to the British (German claims to some part of Buganda would be set aside in years to come).

The Berlin conference meant that while Kabalega was triumphantly expanding his kingdom to its largest size in over 20 years, and while Mwanga was trying to eliminate religious-linked centres of influence from Buganda, their kingdoms were being allocated to imperial powers thousands of miles away.

Mwanga’s ouster

Although the missionaries had, up to that point, played a mostly passive role, they were soon to throw off their robes and seize arms and remove Mwanga.

The Christians and the Muslims put their religious differences aside and, with the support of the British, deposed Mwanga on August 2, 1888, replacing him with his brother Kiweewa as Kabaka. That event marked the first time in recorded history that a foreign, non-African hand had reached through the mists of time to choose the leader of the Kingdom of Buganda. It would not be the last time.

The marriage of convenience between the three religious groups would not last long and would, in a few months, lead to civil war in Buganda.

In the meantime, however, the imperialists, emboldened by the Berlin conference, were circling like vultures and would soon arrive to claim their prize. Buganda and the kingdoms and chiefdoms around it would never be the same again and both Mwanga and Kabalega would soon find that fate had taken them from foes to fugitives and to friends.