How campaign to elect Pope Francis was managed

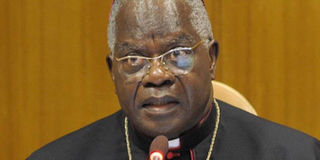

DR Congo’s Cardinal Laurent Monsengwo Pasinya raised a question about Cardinal Jorge Mario Bergoglio’s lung condition. File Photo

What you need to know:

Pope Francis arrives in Uganda this Friday for a three-day pastoral visit. In a three-part series starting today, Associate Editor, Training Tabu Butagira explores how the campaign to elect the Argentine as the Pontiff was executed, the inside story of how one of the 2013 voting rounds was cancelled because there was one extra ballot than number of electors in the Conclave and ongoing reforms that have made the pontiff unpopular within the Vatican’s Roman Curia but popular around the world.

He was first a nightclub bouncer, became a teacher, a Cardinal of Buenos Aires in his native Argentina, and Pope. Such is a solemn life anecdote of Pope Francis, 78, who arrives in Uganda this Friday on his maiden six-day, three-nation Africa pastoral visit.

Cardinal Jorge Mario Bergoglio, who in 2013 swapped his First-class air ticket sent by the Vatican for Economy seating, was not a papabili or probable papal candidate when he flew into Rome.

Pope Benedict XVI had resigned unexpectedly, citing age and failing health, catching the 1.2 billion-strong denomination unprepared to handle a crisis of leadership vacuum with the substantive office holder alive.

In the secluded community of cardinals, Westminster’s now emeritus Archbishop, Cormac Murphy-O’Connor, knew at once that the Argentine was the right fit to fix a Catholic Church plagued at the time by reported administrative malaise, financial impropriety and sexual abuse.

His message was not readily neither warmly received.

For instance, when Murphy-O’Connor approached the Democratic Republic of Congo’s Cardinal Laurent Monsengwo Pasinya, considered the African kingmaker, the latter raised questions about Bergoglio’s lung condition. Neither were the United States cardinals initially receptive.

Unexpected papal vacancy

Benedict XVI without warning resigned on February 28, 2013. “I have come to the certainty that my strengths, due to advanced age, are no longer suited to an adequate exercise of the Petrine mystery,” he said, becoming the first Pope to resign in 600 years.

Far away in South America, Cardinal Bergoglio described the decision as a “revolutionary act”.

There was a crisis at hand: a powerful religious institution with 1.2 billion followers was plunged in sede vacante (papal vacancy). Cardinals run the church in this interim period.

The Vatican convened a sitting of the Cardinals to, among other things, elect Benedict’s successor. It sent all of them air tickets to fly First Class and put limousine ready to chauffeur them from the airport on arrival.

Cardinal Bergoglio, however, changed his air ticket to Economy seating, asking for an exit seat with wider legroom because his sciatica bothered him on long flights. He planned to return to Buenos Aires on March 23, to review homilies he prepared for Easter liturgies.

Bergoglio had, according to Austen Ivereigh, informed Daniel del Regno, a kiosk owner, to continue supplying his copy of the La Nacio’n newspaper promising he would be back within 20 days.

At Fiumicino–Leonardo da Vinci International Airport in Rome, Bergoglio on disembarking carried his luggage and hitched a train ride to Termini station, then swapped to a bus to Via della Scrofa in the Vatican where he checked into a Shs350, 000 ($100) full-board room at Domus Internationalis Paulus VI.

At best, Vatican insiders considered Bergoglio a fringe kingmaker, having been a frontrunner in 2005 when Benedict was picked.

The 151 cardinals began their general congregations in the Synod Hall on March 4, 2013 as workers installed a false floor and jammers in the Sistine chapel ahead of the conclave, Mr Ivereigh writes. Only 115 were under 80 years and, therefore, eligible to vote.

Most were chauffeured in limousines to avoid prying journalists. Cardinal Bergoglio, however, trekked undetected to and from the venue wearing a raincoat.

Italian Cardinal Angelo Raffaele Sodano, the dean of the College of Cardinals and Chamberlain Tarcisio Bertone, both Vatican insiders linked to scandals, were the early favourites to succeed Benedict XVI.

Yet Vatican corruption and dysfunction dominated the behind closed-door cardinals’ meetings, Ivereigh notes, citing media leaks and tidbits US cardinals at the time provided at press conferences under their umbrella body, Pontifical North American College. They mulled over the damaging findings in a 30-page report that three cardinals Benedict appointed prepared.

Separately, the American and German cardinals had received exclusive insider details about graft at the Holy See following a briefing by Papal Nuncio to Washington DC, Archbishop Carlo MariaVigano. They expected a change in the status quo.

“We knew the world awaited the election of a pontiff who might usher in some significant reforms that begged for implementation within the Church,” Ivereigh quotes New York Cardinal Timothy Dolan in his conclave memoir. Besides financial pilfering, the Curia (Vatican administration) was paralysed by patronage that saw less-deserving people “promoted beyond their abilities while the well qualified were sidelined”.

“…[curia] battled a culture of entitlement in which middle-level bureaucrats expected jobs for life, and competence was important than who you knew,” writes Ivereigh.

Mr Ettore Gotti Tedeschi, the reformist head of the powerful Vatican Bank, formally called the Institute for the Works of Religion, had been suspiciously sacked.

Major Italian dioceses opposed Cardinal Angelo Scola, the archbishop of Milan, whom church patriarchs from outside Rome considered a successor to Benedict XVI. The pro-Sodano and pro-Bertone factional fighting, both against Scola, meant the Curia unlike in the past “had no time to stitch up things” before the conclave.

Sodano, a former Vatican secretary of state, was ineligible to vote due to advanced age, but remained an influential operative and rallied support for Sao Paulo Archbishop Odilo Scherer, a former Vatican insider considered pliant.

With Cardinal Odilo Pedro Scherer, Archbishop of São Paulo, as Pope, his backers planned to have Argentine Leonardo Sandri, Sodano’s former deputy, as secretary of state, to ease their way back to influence the Curia decisions. It was a way of restoring the old guards by welcoming easy-to-manipulate outsiders.

The crises reinvigorated previous Bergoglio supporters such as Cardinal Comac Murphy-O’Connor, who was above 80 years and ineligible to vote, together with electors Cardinal Walter Kasper, Godfried Danneels and Karl Lehmann to renew their 2005 wish, according to Ivereigh, a journalist and commentator on religious affairs. Vatican rules debar seeking consent of potential papal candidates beforehand.

“I understand,” Bergoglio replied when Cardinal Murphy-O’Connor taunted him to be “careful” because this election could be his turn.

“Then they got to work, touring the cardinals’ dinners to promote their man, arguing that his age – 76 - should no longer be considered an obstacle, given that popes could resign,” according to details in the book, The Great Reformer.

The campaigners knew from their 2005 Conclave experience that only those with a strong showing stood a chance to be elected a pontiff.

This would mean at least 25 first-round-votes for Bergoglio. Team Bergoglio could count on the nineteen Latin American cardinals, Ivereigh notes. Europeans made up more than half of the electors, and their vote was thus decisive.

Spanish Cardinal Santos Abril y Castelló, Archpriest of the Papal Basilica of St. Mary Major in Rome and an ex-Nuncio in Latin America, vigorously canvassed votes for Bergoglio among the Iberian bloc.

European support was lobbied by, among others, Vienna Cardinal Christoph Schönborn, one of main backers of Joseph Aloisius Ratzinger (Pope Benedict XVI) in 2005, and Parisian Cardinal André Vingt-Trois, who was pro-Bergoglio going into or before the conclave.

Murphy-O’Connor of Westminster rallied support for Bergoglio among especially the 11 and 10 African and Asian English-speaking cardinals, respectively.

The DR Congo Cardinal Laurent Monsengwo Pasinya, presumed kingmaker among African cardinals, asked Bergoglio about his lung condition.

The Argentine bluntly replied that he underwent a surgery in the 1950s, and his lungs have ticked well since.

According to Ivereigh, the 14 American and Canadian cardinals, the biggest number outside Europe, began giving serious consideration to Bergoglio on March 5, the second day of the congregations “when a major dinner was held in the Red Room of the Pontifical North American College, with Murphy-O’Connor of Westminster and Pell of Sydney among guests”.

Their kingmaker was the Chicago Cardinal Francis George, who was initially torn between Sodano and Canadian Marc Ouellet, Ivereigh writes

He notes: “Murphy-O’Connor threw Bergoglio’s name into the ring, but it did not catch fire that evening… [Chicago Francis Eugene] George was particularly worried about Bergoglio’s age. ‘The question is: does he still have vigour,’ he wondered.”

The only pro-Bergoglio American, according to the author, was Boston Cardinal O’Malley, who on a visit to Buenos Aires received an Argentine mass Compact Disc (CD) from Bergoglio, but wielded insignificant influence to sway his American peers.

When the North American cardinals were banned from daily pressers, the leaks projected it as a byzantine contest between Italian and Vatican factions, Ivereigh says.

“For this reason, and because those urging his election stayed carefully below the radar, the Bergoglio bandwagon that began to roll during the week of the congregations went undetected by the media, and to this day most vaticanisti believe there was no organised pre-conclave effort to get Bergoglio elected. Not for the first time, the Argentine would appear to come out of nowhere, like a gaucho galloping in from the pampa at first light from nowhere,” he writes on page 357.

Indeed, during the campaigns and after the vote, the Argentine’s strengths included political charisma and prophetic holiness.

Both manifested when he addressed the cardinals’ general congregation on March 7, leaving them in utter admiration with a speech of just three-and-half minutes.

In Part II tomorrow – we look at the titillating insights into what happens when the cardinals converge to elect a new pope and shut the doors of the Sistine

Chapel to an inquisitive and anxious world.

The numbers

115

The number of Cardinals who took part in electing Pope Francis.

80

The age above which a cardinal is not eligible to take part in voting for a pope.