The importance of good writing

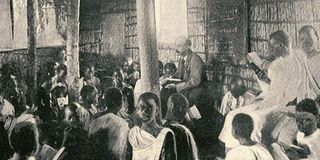

British colonialists teach a group of Ugandan children how to read. British civil servants laid out a survey of the Ugandan economy sector by sector, and stated plans to address the challenges and opportunities in developing the Ugandan economy. FILE PHOTO

What you need to know:

Favour to Uganda. If there is any favour the British government should do us, in the name of development aid, it is not in pouring millions of pounds into Uganda to fund various projects. What it should do, instead, is send Uganda at least 1,000 Britons to work as teachers, civil servants and academics, writes Timothy Kalyegira.

Over the past three years, my knowledge of Uganda and Africa has increased many times over.

I have come to understand Uganda more since 2014 than in all previous years of my life and education put together.

It is not because I have enrolled in a development studies course at a university or belatedly decided to embark on a PhD programme.

Rather, it is because I have taken to reading books and booklets written by the British colonial government in Uganda, by British missionaries, explorers and academics in the 19th Century and up to the mid-1960s.

Reading these books rubs salt into my wounds and reminds me of just how much Uganda lost in the ill-advised rush to “independence” in 1962.

What was the rush for? What was the impatience for?

Where were the Ugandan thinkers to write reports to explain to us that while it was understandable to wish to be free of colonial rule, we were simply not ready to run our country?

Basis of emotion

All over Africa, on the basis of emotion, political grievance and often plain self-seeking, dozens of African countries clamoured for independence without any clue about what that entailed.

Over the last 50 years, there has been so much emotion and opinion expressed over national issues.

The “Buganda question” was for many years the central political issue in the country. Earlier it had been the question of the “Lost Counties”.

Then there was the “Karamoja question” in the 1960s, the “Moshi question” in 1979 and 1980.

There was the “Federo question” in 1994 during the deliberations on the new Constitution.

In 2005, the “question” became one of presidential term limits and since then there is the question of presidential succession and the alleged “Muhoozi Project”.

Tones of newspaper print and thousands of hours of radio and television air time have been exhausted in discussing these questions of the day, none of which really got to the bottom in understanding and explaining the core problems and needs of Uganda.

One wonders what we columnists in our national newspapers and panellists on our radio talk shows are really saying, after reading these books written by the British.

Right now I am reading through a booklet titled The First Five-Year Development Plan, 1961/62-1965/66.

It was printed by the Government Printer in Entebbe and published in July 1962.

In it, British civil servants of the outgoing colonial government laid out a survey of the Ugandan economy sector by sector, and stated plans to address the challenges and opportunities in developing the Ugandan economy.

The main impression I am left with is the sense of harmony that runs through the booklet and the warmth and hope it leaves one with.

Total clarity of ideas and concise, matter-of-fact English come across. There is none of the verbosity and emotion-laded language in our government and corporate reports Uganda these days.

It is clear, from reading through the first five-year development plan, that the colonial government was composed of well-educated, elite-educated civil servants with a solid grasp of the technical operations of government.

The plans for the different sectors all fit into the overall blueprint for the development of Uganda. There is nothing like this in Uganda today.

This five-year development plan has reinforced in my mind why there are few skills as important as the ability to write well, clearly and concisely.

The importance of writing well and clearly can be seen in the intelligence and security services.

It is a beautifully-written document. It is the kind of document that, when one reads it, makes one want to work hard for that government and that country.

It reminds me of the letter the editor of the London newspaper, the Financial Times, wrote to subscribers and readers explaining why the FT was taking a digital-first approach.

Everything flowed well and sounded rational in that letter. Incidentally, the Financial Times is one of those newspapers whose clarity of writing and explanation of the news or trends in various industries leaves me impressed.

In the 1992 book Inside the CIA, a CIA officer explains the paramount place of writing in working at the CIA, America’s foreign intelligence service:

“Exceptional oral and written communication skills are required…You have to write well.” (page 210, 211).

On the face of it, given the CIA’s shady reputation, the ability to climb over walls or blend in with a crowd on a city street under disguise would seem to be the most important quality, but the CIA insists “exceptional” writing and oral skills are paramount.

These books by Uganda’s colonial-era administrators, educators, missionaries and explorers have brought that truth home to me.

On the American travel website, this is the way Jinja Town is described:

“Famous as the historic source of the Nile River, Jinja is these days the adrenaline capital of East Africa. Here you can get your fix of whitewater rafting, kayaking, quad biking, mountain biking and horseback riding in a town with a gorgeous natural setting and some wonderful, crumbling colonial architecture.”

In that short passage, Jinja is well summed up. One gets a mental picture of the town as we know it: on one hand, it has become a magnet of outdoor sports and leisure for Western tourists. On the other hand is the “crumbling colonial architecture”.

Exactly as it is described is what it looks like.

If there is any favour the British government should do us, in the name of development aid, it is not in pouring millions of pounds into Uganda to fund various projects, most of which ends up embezzled or wasted.

What the British government should do, instead, is send Uganda at least 1,000 Britons to work as teachers, civil servants and academics in various towns and institutions in Uganda.

That is where the need is greatest, the need for people gifted with writing skills, analytical minds and that ability to write reports that lend clarity to important national issues.