Besigye trials, tribulations in 2001 and 2006 elections

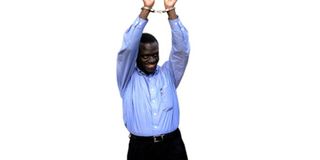

Dr Kizza Besigye waves to his supporters as he leaves the High Court after his bail was granted but was immediately taken to the General Court Martial for another trial in 2005. File photo.

What you need to know:

Part VI. Uganda has had six elections in its 53 years of independence. The forthcoming February 18, general election will, therefore, be the seventh. Save for the 1962 independence election organised by the departing colonial government, the running thread in all the country’s elections has been one malpractice or the other. There have been gains and there have been losses at every electoral turn. In the last part of our series, Saturday Monitor’s Eriasa Mukiibi Sserunjogi looks at some the hurdles that Dr Besigye had to jump before he could get on the ballot paper.

The 2001 election had left a bitter taste in the mouths of Dr Kizza Besigye and his supporters. Some of his supporters, in fact, appeared to believe that should their candidate dispute the results of the election, armed action akin to what President Museveni took after the 1980 election, would follow.

To compound the uncertainty, Dr Besigye refused to denounce rebellion as a possible means of changing government should all legal means fail.

When he broke ranks with Mr Museveni, Dr Besigye claimed he had 90 per cent support in the military. While campaigning in Rakai for the 2001 election, a man handed him a hammer, asking him to knock the “cotter pin”, which President Museveni had called himself years earlier, out of Uganda’s power machine.

After the 2001 election, however, Dr Besigye chose to test the court system by lodging in the Supreme Court a petition challenging Mr Museveni’s re-election, in the process convincing all the five justices that the election had been riddled with irregularities. Three of the five justices, however, upheld the election, reasoning that the irregularities had not substantially affected the final outcome.

In reaction, Dr Besigye pledged to respect the decision of the court, although he said he disagreed with it. Whereas Mr Museveni’s government had been rendered legal by the ruling, he said, “it will never be legitimate”.

“If Mr Museveni chooses the path of repression,” Dr Besigye warned after the ruling, “he will face stiff resistance.”

The State responded by placing Dr Besigye under a 24-hour surveillance and later virtual house arrest at his then home in Luzira. However, on November 3, 2001, he beat the surveillance and escaped to exile, eventually settling in South Africa until October 26, 2005, when he returned to Uganda.

He remained a vocal critic of the government while in exile, and the government in return accused him of preparing for armed action under the auspices of the Peoples Redemption Army (PRA). PRA remained shadowy and facts as to whether it really existed or not remain scanty, but Dr Besigye denied any involvement with rebel activity.

Between 2003 and early 2005, the State arrested a number of alleged rebels, some reportedly from the Democratic Republic of Congo and others from different parts of Uganda. Some 22 of these alleged rebels would be thrust to the centre of one of the bitterest controversies in Uganda’s judicial history.

The now famous 22, including Dr Besigye’s late brother Musasizi Kifeefe, had been detained in different military facilities without any charge until Dr Besigye was arrested shortly after his return to the country. They were then jointly charged with Dr Besigye with treason and misprision of treason. Dr Besigye had a separate charge of rape, allegedly committed in 1997, also slapped on him.

Enter Black Mambas

Then came a hearing of a bail application on November 16, 2005, before the High Court judge Vincent Lugayizi. The Constitutional Court had ruled earlier that bail is a constitutional right and that so long as the applicant satisfied the court that he would show up to attend trial, he would be granted bail regardless of the charges against him. Mr Lugayizi granted 14 of the accused bail.

A Pandora’s Box had been opened. Even before the hearing ended, armed men dressed in black, laid siege on the court and surrounded the holding cells in which those who had been granted bail waited for the paperwork to be done. The men in black, dubbed “Black Mambas” by the press, even entered some offices and sabotaged the processing of bail. In the end, the suspects chose to be returned to Luzira instead of being re-arrested by the Black Mambas.

Then Maj Felix Kulaigye, the army spokesperson, said the Black Mambas had been deployed at the High Court to re-arrest the 22 suspects if they were to be released on bail, because they had new charges to face before the army’s General Court Martial (GCM).

Dr Besigye was himself granted bail on November 25, 2005, but, on the basis of a warrant of commitment on remand issued by the GCM, he was not released.

The charges in the GCM, which were based on the same facts as those before the High Court, were eventually read out to the suspects, who had been picked up from Luzira prison, on November 27, 2005.

Legal experts weighed in with criticism of the double trial – both before the High Court and the GCM. Mr Ronald Naluwairo, a law lecturer, eventually weighed in with an authoritative paper on the trial, titled The trials and tribulations of Rtd Col Dr Kizza Besigye and 22 others (http://huripec.mak.ac.ug/pdfs/Besigye_trials_1.pdf).

The concurrent trials still continued for some time, however, until Dr Besigye applied to the High Court to suspend the trial in the GCM to allow the Constitutional Court to decide on its legality.

The application was granted and Dr Besigye later made another application, prompting the now retired Justice John Bosco Katutsi to declare that Dr Besigye’s continued detention on a warrant of commitment from the GCM was “illegal, unlawful and in contempt of the High Court order to release the applicant on bail.”

He ordered Dr Besigye’s immediate release, which was done on December 19, 2005, but not after President Museveni, responding to queries by diplomats from Europe and the US, issued assurances that Dr Besigye would not be tried in the GCM.

Besigye nominated while in jail

On December 14, 2005, Dr Besigye was nominated to run for president while in jail, but only after a series of arguments.

The most memorable opinion was offered by Dr Kiddhu Makubuya, then Attorney General, who argued that Dr Besigye would not be nominated in jail because, having been arrested over links with “serious crimes”, he was not at the “same level of innocence” as the other candidates and had categorically refused to renounce rebellion although he denied participating in it.

In the end, Mr Adolf Mwesige, then Deputy Attorney General, wrote to the then Internal Affairs minister, Dr Ruhakana Rugunda, clearing Dr Besigye to be nominated while in jail.

The prisons authorities at Luzira, which fall under the docket of the Internal Affairs minister, had confiscated Dr Besigye’s nomination papers and the Electoral Commission had vowed not to nominate him unless he personally showed up at the nomination venue at Namboole stadium.

With this huddle eventually cleared and Dr Besigye finally released, the stage was set for yet another violent election campaign that ended in controversy.