Offering justice out of court

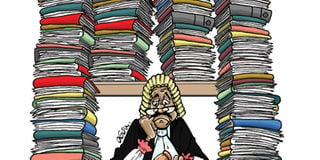

Case backlog is a very big factor delaying justice in Uganda. Chrisogon Atukwase Illustration.

What you need to know:

In this part of our series on the justice system, we look at Plea Bargaining as a way of reducing time and resources spent in the process of settling a case by trial.

It may sometimes be better for an offender’s record if they pleaded guilty. This is because in return, the offender receives a reduction in the number of charges or lessens the seriousness of the offence. This is obviously much better than a conviction that might result from a full-fledged criminal trial.

A guilty plea is the latest initiative from the courts of judicature to reduce on case backlog. With this in place, statistics on case back logs may become a thing of the past.

According to a recent parliamentary report, the Criminal Investigations and Intelligence Directorate investigated 36,778 cases and concluded 13,747 violent crime cases which were submitted to the Director of Public Prosecution (DPP), resulting into 1,886 convictions.

Low convictions

The answer perhaps is in what court users at a recent open court day at Makindye Chief Magistrate’s Court said: “The trial process is long and tedious,” making many victims give up altogether.

These notwithstanding, there are various interventions instituted to curb the rising case backlogs such as small claims procedures, recruiting more judicial officers as well as new sentencing guidelines.

It is against this background that Plea Bargain, a new mechanism set to enhance the effectiveness of the criminal justice system in Uganda for all parties involved in a trial, has been set up.

The judiciary is spearheading this project which was a brain child of former Chief Justice Benjamin Odoki. He set up an 11-man team headed by the Principal Judge, Yorokamu Bamwine, with an overall objective of enhancing the efficiency of the criminal justice system.

The result of this committee’s work can be felt now with the month-long pilot plea bargaining session running from May 26 to June 26.

According to a statement from DPP Mike Chibita to this newspaper, the pilot programme will target the districts of Mubende, Mpigi, Kiboga and Entebbe that fall under the Nakawa High Court circuit.

In his statement, Justice Chibita said out of the 261 inmates who are set to plead guilty on their own, 135 are from Kigo Prison, five from Murchison Bay Luzira prison, and 83 from Mwiyinaina Prison and 17 from upper prison, Luzira.

According to Mr Andrew Khaukha, the secretary of this committee, the team came up with guidelines intended to enhance the efficiency in the criminal justice system through an orderly and timely management of trials. This, he says, will be achieved by encouraging and making provisions for accused persons, willing to plead guilty, to negotiate punishment.

In Uganda, criminal prosecution is handled by the DPP and as such, any party interested in benefitting from this provision has to go through the state attorney. But for now, only accused persons of capital offences can use this scheme.

Asked why he thinks this will enhance the efficiency in the criminal justice system, Mr Khaukha says, if all parties agree, this saves costs of trial, transportation of witnesses and the time of a judge and he or she will still be in position to arrive at a just decision.

The difference with plea bargaining is that the victim is also consulted and after which all parties can then sign a plea bargain agreement. It is on this agreement that terms are clearly stipulated – say a reduced charge from murder to manslaughter or simply a reduced sentence.

But that is not all, the accused and witnesses are both saved from the anxiety of criminal prosecution and it also helps the victim in the adjudication process. In trials, usually the victim only gives an account of what happened, but with this agreement, the victim contributes in the sentence thus promoting public participation.

This initiative is not a lone campaign of the judiciary, other stakeholders are also involved. For example, the Ministry of Gender is helping in the re-integration process by sending welfare officers to the community to assess their views before offenders can go back to their communities.

What next after the pilot?

Mr Khaukha says after the pilot session, the committee will submit their assessment to the Chief Justice for consideration. The principal judge has constituted a team of five high court judges to steer the pilot with Justice Lameck Mukasa handling Mubende, Justice Wilson Masalu-Musene handling Kiboga, Justice Henry Adonyo taking Mpigi, Justice Lawrence Gidudu handling Nakawa and Lady Justice Elizabeth Nahamya handling Entebbe.

Similarly, the DPP has also set up a team of 10 state attorneys to participate in this pilot. Uganda Law Society has also constituted a team of state lawyers to negotiate on behalf of the accused persons.

The Officer in Charge of male prisons in Kigo, Mr Moses Ssentalo, will participate in this exercise while Moses Kabogoza, the assistant commissioner probation in the Ministry of Gender Labour and Social Development, will liaise with welfare officers to guide court in coming up with a sentence agreeable to parties.

One thing that stands out is that all stakeholders agree that this is an effort that will go a long way in reducing case backlog and decongesting prisons as well as saving the government the cost of criminal trials and management of inmates in prisons.

This system has worked in USA and substantially reduced the cost of criminal trials. In the case of Uganda, more than 200 offenders are going to benefit from the pilot and the whole project is being monitored by the office of the Principal Judge.

So why is this being implemented now?

Mr Khaukha says in the past, the Judiciary has come up with many of initiatives like quick win sessions, plea of guilt sessions, sentencing guidelines and recruiting of judges and magistrates to ease case backlog but it has been realised that there is need to add another initiative.

According to the DPP, the number of people involved in a trial as witnesses will be reduced from an average of seven witnesses to just the victim and the accused person. The other five people can instead take part in more productive activities at their workplaces, which reduces on the amount of time spent in court.

But isn’t this a case of duplicating initiatives? Mr Khaukha vehemently disagrees with this assertion. He says in the case of sentencing guidelines, offenders can only guess sentences. Besides, the guidelines only apply after someone has been convicted of an offence and they are being used to guide court to arrive at a just sentence in all the different sessions.

He adds that in normal plea of guilt sessions, an offender cannot determine the sentence. He explains that in plea bargaining, the offender signs the plea bargain agreement before going to court.

Asked whether there is a legal framework for plea bargaining, he says no, but quickly adds that the taskforce has guidelines that are supposed to be issued by the rules committee either as rules or practice directions.

What is plea bargaining?

Plea bargaining is a negotiated agreement between the prosecution and an accused person who is represented by a lawyer. The accused person then comes before a judge to plead guilty to the charges against him/her in exchange for a lesser sentence without going through a full trial.

How the plea bargain works

In every criminal session, a judge is supposed to handle 40 cases. The cost of each trial is estimated to be Shs1m. This money is supposed to cater for transport of the judge, allowance for his body guard, state brief lawyers, clerks, witnesses, police and the investigating officers. However, with plea bargaining, the costs are cut by half.

The pilot focused on the High Court because that is where case backlog is most pronounced. But these sessions will eventually be spread to all courts.

Who is involved in the process?

Court

Prosecution

Accused person/ counsel

Victims

Probation officers

Procedure at the hearing

• The agreement must be explained to the accused by an advocate, justice of peace or interpreter.

• Prosecution must take into account the victim’s interests.

• Implications of the agreement must be explained to him/her and court must be sure that it is not obtained under force, coercion or misrepresentation of facts.