Tired of humiliation, Mwanga revolts

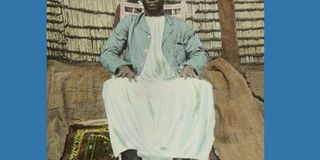

Kabaka Mwanga II ruled Buganda from 1884 to 1897, during which he was dethroned thrice, but not without putting up a fight. Photo by HIPUganda/www.HIPUganda.org

What you need to know:

With the British forces distracted by their adventures against Kabalega in Bunyoro and an uprising by the Nandi in Kenya, Kabaka Mwanga finally mustered the courage to try and break free of the humiliating yoke in which he had been placed.

Kabaka Mwanga’s throne might have had a touch of royalty with his sandal-bearing feet resting on a leopard skin but by the time he was restored to his throne for the third time in 1892, he was little more than a paper tiger. He was only returned because the throne needed a king and he was the only royal available or acceptable to the British and their local collaborators.

Real authority now lay in the hands of the two Katikkiros; the Protestant Apolo Kaggwa and the Catholic Stanislus Mugwanya who lost no opportunity to embarrass and humiliate the king.

The Kabaka had already lost the power to declare war. The Lukiiko (parliament), which he had previously lorded over and appointed members to, had now taken on republican tendencies under the Katikkiros. He was not allowed to attend.

Tied hands

More injustices were to follow, including restrictions to his authority to trade in ivory, which the British had now assumed monopoly rights to.

In one incident, Mwanga was fined 3,300 pounds of ivory for exporting 2,300 pounds of the stuff to Zanzibar without approval of the British authorities. Although his subjects chipped in to help the king pay the fine, the humiliation had already left its mark.

More importantly, Prof. Samwiri Lwanga-Lunyiigo notes in his book, Struggle for Land in Buganda, that the British attempted to break Mwanga’s central authority as ‘Ssabataka’ or Buganda’s principal land trustee by offering to register, for a fee, land in private names.

Up to that point the giving (and taking away) of land was a major lever through which the Kabaka dispensed patronage and punishment. Now the power had been usurped by the British to widen the fissures between the Kabaka and his subjects.

Secret plot

Despite all the public humiliation, Mwanga was secretly plotting a revolt. His trade in ivory, while it lasted, and before the Belgians arrested and executed his gunrunner Charles Stokes in the Congo, had allowed Mwanga to assemble a formidable arsenal, which he hid in Bulingugwe Island.

Although he did not have his father Mutesa’s cunning of playing one faction against the other, Mwanga demonstrated some deftness in alliance-building, arranging for his sisters to marry two Baganda military generals, Gabudyeri Kintu and Semei Kakungulu, who had played a key role in the earlier fight against the Muslim faction.

By 1897, Mwanga was ready to set his plan into action. The British forces had been split with sections sent to Busoga and to present-day Kenya to put down uprisings there, while those who were hunting down Omukama Kabalega in Bunyoro had suffered major reversals, including the death of at least one British officer, and were demoralised.

The British invincibility had also been peeled away by Kabalega’s dogged war of resistance and Mwanga, who had been both victim and beneficiary of religious differences in Buganda, now sought to transcend those dogmatic differences through a nationalist ideology.

The Catholic historian, Prof. John Mary Waliggo, summed up Mwanga’s ideology writing in his PhD thesis: “The period between 1892-7 can well be seen as one of Mwanga’s strategy to deceive both the administration, the Protestant Party and the Catholics loyal to the administration.

“It was the time in which having tried all available alternatives, Mwanga began to form his own party to challenge the two-party system of the Christians. His party was based not on any one religion but on the common element that appealed to most Baganda, the opposition to white rule.”By the time he fled his capital, Mengo, on July 6, 1897, it was estimated that Mwanga had about 14,000 men armed with spears and 3,000 guns.

Prof. Lunyiigo has argued that the two opposing sides were evenly matched, save for the Maxim guns and Hotchkiss machine gun that the British had.

Spears Vs gun

War broke out on July 20, 1897 but Mwanga’s forces under the command of Lui Kibanyi were quickly routed in battle at Kabuwoko in Buddu. Mwanga’s forces had underestimated the ferocious power of the Maxim and were scattered but not before giving a good account of themselves.

Prof. Lunyiigo’s book reveals how one of Mwanga’s men, Lui Nkoowe, stealthily approached the Sudanese soldiers operating the Maxim gun, speared him to death and tried, unsuccessfully, to capture the feared gun.

Writing in Buganda in the Heroic Age, Michael Wright would admit that, “It was a close-run thing. Had the second Maxim jammed, the most crucial battle in Buddu…could easily have gone the other way.”

Kabaka Mwanga was himself not part of the fighting and now made his way along the Kagera River to Kasenyi, which was now part of the German Protectorate.

The Germans initially offered Mwanga sanctuary in Kasenyi but not for long. Bishop Joseph Hirth who had harboured ambitions of carving out a Catholic kingdom in Buganda had since been replaced by Bishop Henri Streicher who was more interested in cooperating with the British.

Bishop Streicher, partly under the pressure of the British and through his own considerations, warned the Germans against sheltering Mwanga, especially very close to his people on Lake Nalubaale.

Bishop Streicher had earlier learnt of rumours about the planned uprising and had written to the colonial officials in Kampala warning them that, “About 100 chiefs tired of your authority and attracted by the hope of regaining their independence are ready to take up arms against the government or at least to desert their country enmass and fly to a strange land where they hope to live in a state of independence.”

The Catholics were using the confession booths to spy on the plotters and had good evidence, but the colonial officials in Kampala did not take the warning seriously enough then.

In any case, the Germans initially moved Mwanga farther away to Mwanza but, when Bishop Streicher continued his warnings, they arrested the Kabaka and put him under full-time observation.

Mwanga was now prisoner in a foreign land and his army defeated. His army reassembled in Masaka near Villa Maria but they were soon detected, inviting Major. Trevor Ternan with the Maxim gun in tow.

As Prof. Lunyiigo retells it, the Maxim gun was assembled on Nyendo Hill on August 23, 1897 leading to another “massacre” and “disaster” for Mwanga’s army.

Although the situation looked bleak, the Sudanese troops in Uganda were about to mutiny and bring the colonial adventure to its knees.

Mwanga was also about to spring one of the most daring escapes and, together with Kabalega, make the last stand for the two greatest kingdoms of the day.

The sun was beginning to set on the traditional kingdoms but the two warriors who led them were not willing to go down without a fight.

Continues Monday