The origin of Democratic Party: Part II

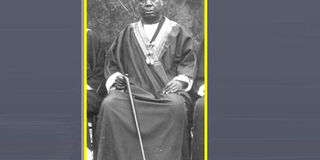

Stanslaus Mugwanya was the leader of the Catholic forces in the 1890s. COURTESY PHOTO

What you need to know:

Having laid out the initial events that in part explain the root causes of Uganda’s current religious schism, last week, in the second and last of our two part series, senior citizen Yoga Adhola brings us to the events of later days that eventually broke the camel’s back and ultimately gave birth to the formation of the Democratic Party, which today is relic of fierce religious fights and divisions in Uganda’s history.

In exile in Ankole, the Catholics and Protestants settled in separate locations, thus continuing to reinforce the two camps. There was perpetual animosity as Nikodemu Sebwato, one of the Protestant leaders who later became Sekibobo (County chief of Kyagwe) was to write to Alexander Mackay: “..... when we left Buganda we came in two crowds. We and our brothers who are followers of the Pope. But we do not pull well together. They want always to fight with us ....”

The animosity was so strong that one time, in the early days of exile in Ankole, when rumour spread that Mwanga was with Mackay turning into a Protestant there was intense fury in the Catholic ranks and some even said it would be better to fight them than be ruled later by Protestants.

Paradoxically, even the protracted campaign to depose the Muslims, a situation which should have served to unify them into a single monolithic Christian party, instead contributed a great deal to reinforce their differences.

Each faction was sustained in the struggle by a vision of the particular kind of future Buganda they wished to establish; the longer the struggle and the more sacrifice it demanded, the less likely it was that either party would give up any of its eventual gains.

Treaty of equality

It was therefore, no surprise that the allocation of offices after the victory over the Muslim party, became virtually intractable. On the intervention of the respective missionaries who had by then become the real leaders of the religio-political parties, a treaty stipulating equal sharing of offices was drawn.

“Alternate ranks in one vertical hierarchy,” the treaty stipulated, “should be held by members of opposite parties. .. (27) Further, to maintain the balance which was the principal objective of the agreement, every chief who changed his religion had to forfeit his political office.”

Thus the treaty became an expression of a marked politicization of religion in Buganda and an indication of the fact that religious divisions had by now become the main stratifying principle in society. ..In other words two rival social forces, though taking a religious coloration, had been set off.

It was in the throes of the mounting intense rivalry between these two nascent social forces that envoys from various imperial countries entered Buganda with the purpose of making treaties of colonisation.

The situation was extremely vulnerable for foreign contention: Both religio-political parties jointly and separately were on the look out for outside support that would guarantee them the military means necessary to keep the Muslims in check, while advancing or at least not retarding their own internal competitive position.

The need for external assistance on the part of the Protestants grew acute as the balance of power increasingly shifted away from them. The main force which influenced this shift was the institution of the Kabaka.

As the Kabaka had become a Catholic, the vast majority of Baganda peasants followed his lead and became Catholic. As this flow into Catholicism continued, the Protestants, in due course, saw their salvation in the Imperial British East African Company (IBEAC) which had arrived in the area. IBEAC being a British company, the Protestants who were the supporters of the English mission, the CMS, logically expected it to lend them support.

Fear to lose influence

The Catholics on the other hand clearly identified British political power with the Protestant religion and they feared that once the British assumed control, the Catholics would in consequence be removed from position of influence. They therefore preferred that the Germans rather than the British take control; and for that matter even signed a treaty with a German envoy, Carl Peters, in February 1890.

This diplomatic contest between the Germans and the British was amicably brought to an end when the two powers in July 1890 signed a treaty which placed Buganda under British sovereignty.

The internal conflict between the Catholics and Protestants was resolved in a war which broke out on January 24, 1892. In this brief war, Captain Lugard, the leader of IBEAC, who had been instructed to “consolidate the Protestant party” lent support to the Protestants who were under the leadership of Apollo Kagwa.

The outcome of the war was a decisive defeat of the Catholics led by Kabaka Mwanga and Stanislaus Mugwanya. The defeat of the Catholic party broke the backbone of any resistance to British supremacy and brought to dominance the Protestant party, a social force which was wholly dependent on the British.

However, Lugard was under no illusions: he still expected hostility from the Catholic party and therefore saw his principal task as creating an equilibrium which simultaneously would emasculate and involve the Catholics in the political and social affairs of Buganda; in any case his instruction was to “attempt by all means in your power to conciliate the Roman Catholics...”

Lugard on new mission

Realisiing that with the Baganda, for any arrangement to have legitimacy, the Kabaka must be involved, Lugard set about to fill the Kabakaship. Two months of hard bargaining with the Catholics enabled Mwanga to return to his throne and a treaty was concluded between the Kabaka and IBEAC, fully recognising British protection and supremacy of the company.

Shortly after returning and largely as a result of differences which had arisen between Mwanga and the Catholic leaders, Mwanga changed his religion and became Protestant. This had two major consequences. First, it enabled the strongest and most loyal force to the IBEAC to merge with the centre of legitimacy in Buganda.

And this led to the next consequence: while the Protestants could now take advantage of a Protestant orientated Kabaka, the others had to look to another centre of power, the IBEAC for the protection and guarantee of their rights. Through this, Lugard acquired a political base which was later recognised in the revision of the treaty whereby the British representative got formal access to and influence on the real centre of power in Buganda.

To placate the Catholics, the county of Buddu was to be exclusively for Catholics and people of other religions had to move to other areas. The Muslims were allocated three small counties which were deliberately situated as buffer between the Catholics and Protestants.

The result of the land apportionment was to secure for the Protestants 60/70 per cent of Buganda.

With regard to chieftainship, the Protestant Katikkiro continued in office and so did the Catholic Kimbugwe as the next highest ranking official; the Protestants secured six county chieftainships, the Muslims three and Catholics one, namely Buddu. The lower ranking chiefs were, it was stipulated, to be of the same religion as their respective county chiefs.

This arrangement was obviously not viewed with satisfaction by the Catholics. There still remained some aspects of the arrangement likely to give rise to tension. The potential for tension was removed when Portal returned to Uganda and consolidated the religious equilibrium by reducing and even eliminating possible sources of dissatisfaction.

This was achieved to a considerable degree by elevating the status of Catholics who up to then were being treated as the vanquished. Not only were the Catholics accorded fairer and more responsible positions in Buganda, they were also granted more territory. In concrete terms the important chieftainships such as Katikkiro had to be held by two people concurrently, one Catholic and the other Protestant.

To placate the Protestant party who were expectantly unhappy with this sharing arrangement, there was a provision to the effect that the Protestant chiefs would take precedence over Catholic ones holding similar offices. With regards to territory, the Catholics acquired one more county, Kaima, one sub-county and the Ssese Islands which were constituted into a county.

Acceptable deal

This new arrangement, to a large measure, was acceptable to both parties and both Bishop Hirth, on behalf of the Catholics, and Bishop Tucker for the Protestants, pledged to bring pressure to bear on their respective followers to accept the arrangement. Much as the Catholics were treated as second class subjects of the Kabaka and were uneasy about it, there was not much they could do.

A Catholic could not be Katikkiro. The highest post in the kingdom that a Catholic could aspire to was the Omuwanika. There had always been 10 Protestant county chiefs, compared with eight Catholics; and in the Kabaka’s government which was formed in 1955 four of the Ministers were Protestants, one a Mohammedan, and only one a Catholic.

To make matters worse, in 1955 Matayo Mugwanya, a Catholic and the grandson of Stanslaus Mugwanya, the leader of the Catholic forces during the 1892 war, contested for the post of Katikkiro of Buganda. He came within three votes of being elected Katikkiro of Buganda. .

With the political awakening on the eve of colonialism, the Catholics organised themselves in a political party called the Democratic Party to redress themselves of their minority status. Ironically the first President of the party was Matayo Mugwanya, the grandson of Stanslaus Mugwanya.