How a fight over beer permits led to Apolo Kaggwa’s resignation

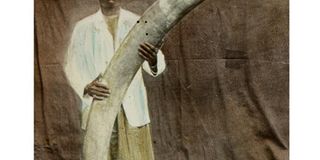

Apolo Kaggwa holds a tusk of ivory. The Katikkiro was the biggest collaborator of the British and helped entrench their colonial rule in Uganda but died on his knees.

What you need to know:

The fall of a Katikkiro. Before continuing with the story of the colonial economy and politics, it is crucial to put away the story of how Sir Apolo Kaggwa, the man who worked so hard to help the British establish their rule, was finally stabbed in the back by his erstwhile allies.

Kampala

In the end, it took a lousy bunch of beer permits to fell the great Sir Apolo Kaggwa and end his 33-year reign as Katikkiro of Buganda and the most important man in the Kingdom.

In an effort to curb idleness and drunkenness (but also to encourage the hard work that would provide more cash crops and taxes), the Baganda chiefs had come under a lot of pressure from the colonial administrators to clamp down on excessive consumption of alcohol.

A law was passed in 1917 limiting the consumption of alcohol in Buganda. It was followed by “the 1925 Declaration Prohibiting the Sale of Beer in Restaurants and the big Roads used by cars, with a view of combating drunkenness in Buganda”.

The new law imposed controls on where beer could be sold and made it a crime for excessive drinking and “laziness resulting from drunkenness which forbids men to do work required of them by the Government or work for themselves”.

To make the law operational, the Lukiiko set up a system whereby its Secretary would issue permits allowing people to bring alcohol into the city.

A problem immediately arose because, while it was the Secretary to the Lukiiko who issued the permits, it was the person in charge of the city, Omukulu W’ekibuga, who was responsible for policing and ensuring the permits were not abused.

In his book, Why Sir Apolo Kaggwa Resigned, Kabaka Daudi Chwa then records a flurry of official correspondence between the Omukulu W’ekibuga Samwiri Wamala who wanted to countersign the beer permits allocated, and the acting Secretary to the Lukiiko Musa Kauma who believed his colleague was overstepping his authority.

When Yusufu Bamutta became Secretary to the Lukiiko in April 1924, he discontinued the practice of collaborating with Wamala. This caused a storm and a flurry of letters were exchanged until Sir Apolo Kaggwa sought to bring the matter to an end, ruling on July 13, 1925 that the permits did not have to be counter-signed or shown to Wamala after being issued by the Secretary.

This should have rested the matter. However, the British came to know about the matter and J.C.R. Sturrock, the Provincial Commissioner in charge of Buganda wrote to the Katikkiro, admonishing him for a change in position and undermining the efforts to curb excessive drinking in Buganda.

Kaggwa was incensed. As far as he was concerned the Buganda Lukiiko was dealing with the matter as it saw fit; involving the British colonial administrators was bypassing the native administration and undermining the authority of the Lukiiko and that of the Kabaka.

Katikkiro protests

“In conclusion,” he ended a letter of protest to John Rutherford Parkin Postlethwaite, who was acting commissioner while Sturrock was on leave, “I beg to inform you that in future the Buganda Government is not prepared to regard as right and to take into consideration matters conducted after this fashion.”

There had been history between Kaggwa and Postlethwaite. The Katikkiro would later claim that the latter had refused to offer employment to some Baganda in Mubende, where he was posted at the time, after he learnt that they were related to Kaggwa.

Postlethwaite took great exception to Kaggwa’s letter. He wrote back a few days noting: “I will be pleased to know if you are prepared to withdraw the last part of your letter…and ask for forgiveness for the same, or else I will take further steps.”

Kaggwa refused to apologise, pointing out that he was not aware of what he had written that had so upset the acting commissioner. This sparked off another flurry of letters, drawing in the Governor at Entebbe.

The correspondence, which makes up most of Kabaka Chwa’s book, is rather revealing about the nature of the relationship between the colonial administration and the native one.

In one letter Postlethwaite demands for the Kabaka to go see him, setting the time regardless of whether or not it is convenient to the king. In many of the letters, the colonial administration officials ask Kabaka Chwa to pass on information to Kaggwa, although the former was supposed to be the head of the native administration.

While Kaggwa was the real power in Buganda, the exchanges do not leave any doubt as to who the power was in the country, with the Kabaka supplicating himself before the colonial officers in his letters.

Kaggwa was right in pointing out that local issues had to be raised with and handled by the native administration, only being referred to the colonial administration if they weren’t resolved satisfactorily.

Kabaka Chwa attempted to support him in this effort but was quickly put back in his place by the Governor through a couple of condescending letters.

The colonial administration raised the ante and encouraged Kaggwa’s friend and personal physician, Dr Cook, to write a letter urging him to resign on account of ill health. When Kaggwa inquired from Dr Cook, the physician confirmed that while Kaggwa’s health was a matter of concern, he had been asked to write the letter by Postlethwaite.

Kaggwa resisted and now sought the intervention of the Colonial Secretary back in London. He said he would only resign if asked to do so by the Kabaka, not at the behest of the colonial administration. He attempted to travel to London and present the matter there but was talked out of the journey by Kabaka Chwa on account of the toil it would subject to his health.

He eventually wrote a long and deeply personal letter, pointing out his role in establishing British rule over Buganda and the efforts he had taken to save the lives of British officials during the periods of war and tension.

“Allow me sir to remind you again that I was the chief figure in inviting British rule to this country and I have given the best part of my life to this country and for the well being of its people and the life of the Europeans especially the British in the days of unrest of the wars of Religion,” Kaggwa wrote.

The matter went on through the second half of 1925 and the first half of 1926 with the British unrelenting and continuing to press the Kabaka to force Kaggwa’s hand.

Katikkiro on his knees

On July 22, 1926, the Kabaka returned to his palace at Mengo and found Kaggwa waiting for him. He hid the Magambira, the instrument of power, behind a chair and handed the king his resignation letter.

Kabaka Chwa asked him to put off his resignation until the king’s birthday on August 8 but Kaggwa refused. He knelt down and handed back the Magambira to the Kabaka.

After 33 years as the most powerful man in Buganda, the very people he had helped bring to power had reduced Sir Apolo Kaggwa to his knees. He died the next year.