Okot p’Bitek’s 1953 debut novel still relevant half a century later

What you need to know:

Book Review.The strenght of Okot’s message in White Teeth remains alive todate as it draws from issues that are still common in our society today.

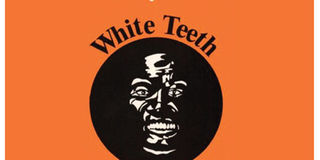

At the age of 22, Okot p’Bitek wrote his first major work that turned out to be the only novel he wrote. The novel was first published in 1953 by the East African Literature Bureau, Eagle Press, and written in Acholi language under the title Lak Tar Miyo Kinyero Wilobo (White Teeth make us laugh on earth) shortened as Lak Tar (White Teeth).

Okot, who died in July 1982, is arguably Uganda’s lone export to the international literary scene, with an African epic poetry style named after him as the Okot song school of poetry. One of his poems, Song of Lawino has been recognised as one of the top 100 African books of the twentieth century. But Okot’ genius was not limited to poetry. White Teeth is arguably the first ever written Ugandan novel.

According to Caroline Auma Okot p’Bitek, the wife of the famous writer, Okot translated the novel himself from Acholi to English before he died in July 1982. Two of the translated chapters appeared in a collection of his essays, Artist, the Ruler as he hoped to put final touches to the translation which according to his widow was not possible, as he died in July 1982 before he could finish the last editing. July 2012 will see the thirtieth anniversary of the passing of a literary genius.

The novel White Teeth rotates around a young man, Okeca Ladwong, who explains his problems that lead him to leave home at age 35 thus, “There was no clansman willing and ready to marry me a wife. I was like a pauper, lapang-cla. You may liken me to one of the homeless that roamed the streets of our big towns. My mother comes from Atyak Lwani. But mother’s people too have refused to marry me Cecilia Laliya.”

Okeca headed south to Kampala to find the bride price money on his own. While in Kampala, he goes through several experiences that expose him to the unfairness of life under colonial rule. He gets arrested and imprisoned for causing commotion in town, a case he wins in court, and then suffers the bitterness of the tongues of his host’s two wives who never tired to tell him of his worthlessness!

He ends up as a worker at Kakira Sugar Works in Jinja, where he rises through the ranks up to junior nyampara only to be killed by kindness and generosity when he helped a fellow Acholi to getaway from work under the guise of going to bury a relative. Disillusioned by the turn of events, Ladwong decides to return to Acholi-land with the little he had worked for, which is robbed on his way back.

When Okeca is mocked by fellow passengers for having left home at all after he is robbed, he questions at page 103, “But why blame me for leaving home? They should blame the ones who become rich by selling their daughters at high prices.

Marrying in Acholiland has now become a big money business. To imagine that the government was against the sale of human beings!” Okeca found himself without even sufficient bus-fare to his home, and as he says in the last sentence of the novel, he discovers that “That distance was for nothing…”

White Teeth and what Okeca sees in his quest for money to pay bride price, although written in 1953, during the colonial era, remains relevant to the Uganda we live in today. Bride wealth remains an issue in society today, as much as corruption in public offices, notably the police force, erosion of clan structures and other cultural set-ups and worker exploitation is not history as well. These vices that a 22- year-old Okot criticised have only increased with more monetisation of the economy.

Even when Okot himself always noted that translation of his works from Acholi to English made them lose the flavor they have/had in Acholi, his writing style remains unmistakably Acholi. As Lubwa P’Chong notes in a foreword to East African Educational Publishers Limited publication of White Teeth, Okot always grumbled insidiously that the lack of equivalent terms and vocabularies for colloquial Acholi terms would affect the meaning of the work. But the strength of Okot’s message in White Teeth remains alive, to date.