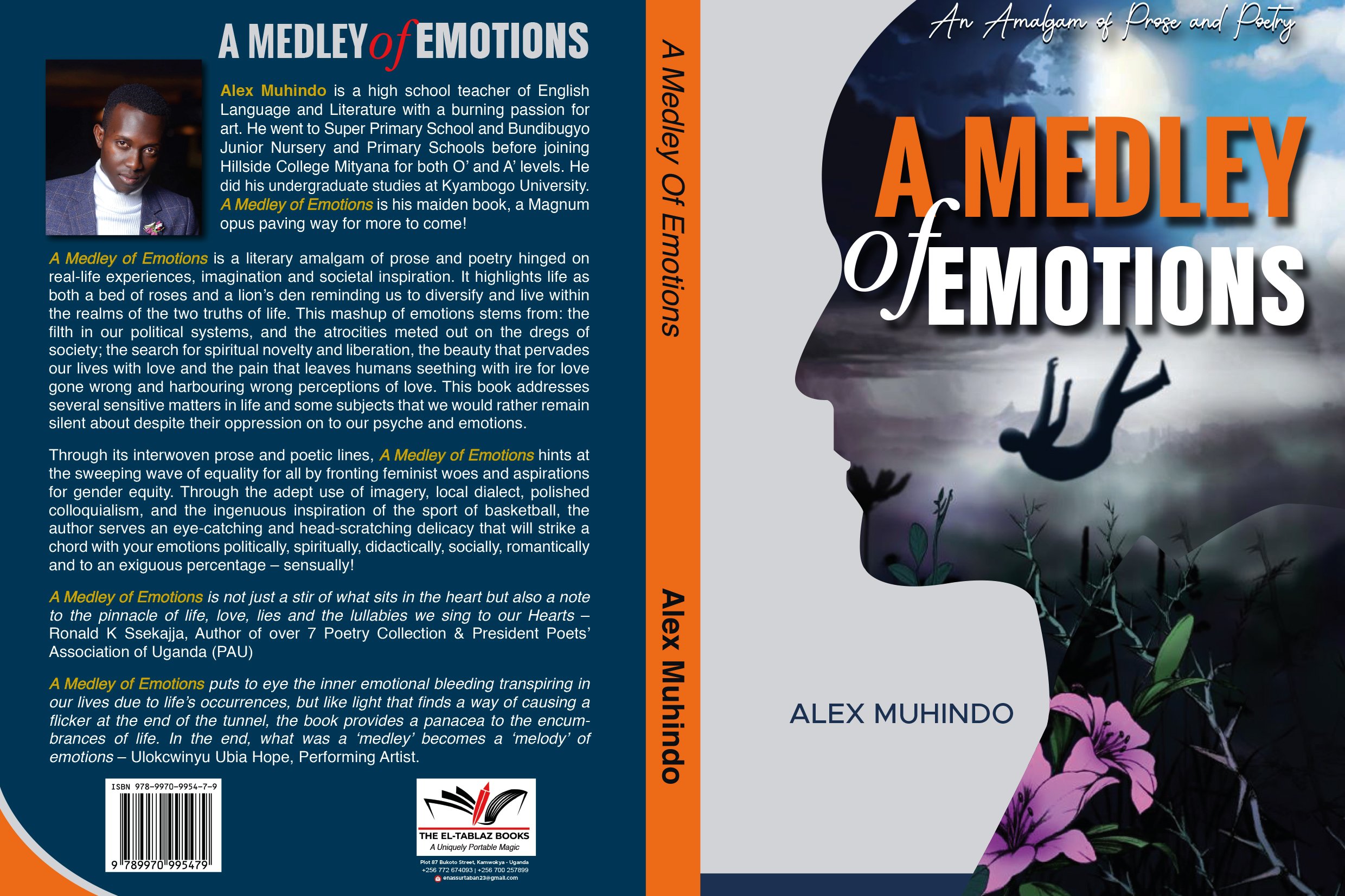

Book Review: Breaking down layers of colonialists’ power

What you need to know:

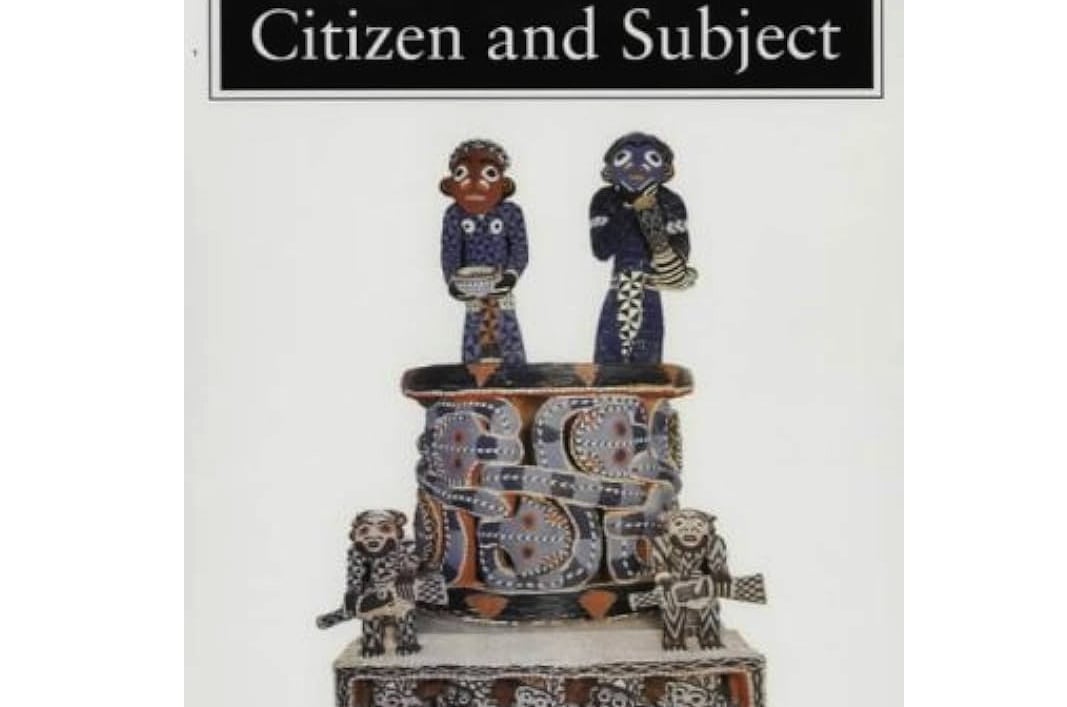

- Book title: Citizen and Subject: Contemporary Africa and the Legacy of Late Colonialism.

- Author: Mahmood Mamdani

- Price: Shs50,000

- Pages: 353

- Where: Aristoc Bookshop

The African state is a somewhat schizophrenic expression of the dualism of power. To be sure, its politics is located in the urban and rural, modernist and communitarian. So it tends towards reform by championing rights over customs as it promotes customs over rights.

All the while, the rural and the urban are linked through political (clientelism) and administrative (coercive) means born of the force of persuasion and the persuasion of force. This duality not only truncates reforms, it leaves the state bifurcated.

Citizen and Subject: Contemporary Africa and the Legacy of Late Colonialism by Prof Mahmood Mamdani problematises and explores this duality in the context of colonialism’s legacy.

In clear and largely poetic prose, Prof Mamdani examines how colonialism was not the cut-and-dried phenomenon that many an Afro-pessimist would have you believe. To Afro-pessimists, Africa should be re-colonised because it has failed (and will continue to fail) in rejuvenating itself from within.

However, colonialism was more of a bane than a boon to Africa in the way it crystallised representation and control as mediatory channels of racial domination through tribally organised local authorities, thereby “reproducing racial identity in citizens and ethnic identity in subjects.”

Prof Mamdani also shows how the forms of colonial rule—“direct” (French) or “indirect” (British)—were actually Janus-faces of despotism. A third variant was also Apartheid which, Mamdani shows, was indirect rule in its primary colours, no pun intended.

He shows how direct rule denied rights to subjects on racial grounds.

In this way, the British were really the harbingers of Apartheid and the French policy of association as they effectively demonstrated the authoritarian possibilities in culture, and by giving culture an authoritarian bent.

To Mamdani, indirect rule was really decentralised despotism as it masked its true dictatorial character through representation, by allowing traditional authorities to bloom, as it were, as a means of control and a mode of colonial penetration.

The sheep’s clothing of custom and culture helped the colonial powers wolf down the buffet of countries served up to them by the Berlin Conference in 1884-1885, which formalised the Scramble and Partition of Africa.

Mamdani divides this book into two parts, which is a form of dualism too. Stale jokes aside, the first section of this book looks at the structure of the state. As slavery ended in the western hemisphere and on the African continent, a new regime of compulsions was necessary.

These compulsions were drawn from the imperial powers’ colonial experiences in Asia. The lessons learnt from these experiences spawned indirect rule as the bastard child of a colonial artifice applied in Equatorial Africa and completed in South Africa.

Mamdani writes, with regard to this evolution of colonial rule, that “the British theorised the colonial state as less a territorial construct than cultural one.” It was a form of political judo, using your opponent’s strength against your opponent. In this case, that strength was the African’s culture.

Out of this, a duality of customary and civil power reflected a legal dualism where “received (modern) law with the customary law” took hold. The customary laws were a set of tribal laws instead of single native law.

This fragmentation of law could be said to provide the legal foundation of a system of divide and rule as each ethnic group had its distinctive law and was, as a result, distinct and easier to rule.

Mamdani also looks at decentralised despotism, characterised by the relation between the free peasant and the Native Authority (read Colonial Authority).

The second part of this book explores that varying thrusts, if you will, of African oppositional movements as they grew out of “the womb of the bifurcated state.”

Mamdani uses South Africa and Uganda as “paradigm cases” to highlight the rural and urban contexts of resistance. Here he explores rural-based movements in Equatorial Africa, with an emphasis on Uganda, and urban-based movements in South Africa. These movements in South Africa sprang into being as trade unions and then later found expression as political parties.

In Chapter 8, Mamdani examines how these movements and post-independent states attempted to navigate the tensions that the structure of power “tends to reproduce in the social anatomy.

My point is that key to a reform of the bifurcated states and to any theoretical analysis that would lead to such a reform must be an endeavour to link the urban and rural—and thereby a series of related binary opposites such as rights and customs, representation and participation, centralisation and decentralisation, civil society and community—in ways that have yet to be done.”

Similarly, this book will serve as an intellectual frame of reference to the bleeding heart pan-Africanist. In so doing, it will narrow their sweeping arguments against colonialism into specificities which will, in turn, widen their appreciation of the colonial experience.

It will also remind the Afro-pessimist who sings “no hope, no change” with respect to the African experience that colonialism fundamentally altered the course of African history.