Amin, Kibedi clash over Ben Kiwanuka’s killing

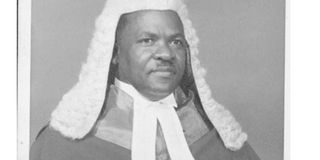

Former Chief Justice Ben Kiwanuka. Courtesy photo

In May 1974, Niall MacDermot, then secretary-general of the International Commission of Jurists (ICJ) released a report titled: ‘Violation of human rights and the rule of law in Uganda’.

ICJ is a Geneva-based international human rights non-governmental organisation that carries out advocacy and policy work aimed at strengthening the role of lawyers and judges in protecting and promoting human rights and the rule of law.

The report was very critical of the Amin regime, which was just one year in power, heaping diplomatic pressure on Amin to respond to the allegations in the report. Amin announced a commission of inquiry into the disappearances.

On June 30, 1974, Amin issued legal notice number 2 of 1974. The notice did set up a commission called, ‘Commission of inquiry into the disappearances of people in Uganda since 25 January 1971’.

It was a four-man commission, including its chairman (who was a justice of the High Court, Justice Mohamed Saied), two Superintendents of Police and an army captain S.M. Kyefulumya, A. Esar and Captain Haruna, respectively.

Later on, two more people were added on the commission. These were C.K Ndozireho (a Kampala-based advocate, who joined as a secretary) and J.N. Mulenga (who was the counsel to the commission), raising the numbers to six.

Although initially the commission had been given up to end of September to have completed its work, the time limit was waived to do an extensive investigation.

A total of 308 cases of disappearance between January 25, 1971 and June 1974, when the commission was set up, were reported, with 529 witness appearing before the commission.

Among the cases that were looked into was the disappearance of Chief Justice Benedecto Kiwanuka.

Recorded as case number 59, a total of six witnesses appeared before the commission, plus one affidavit. The six included his bodyguard, two police officers, his driver, an employee in the motor vehicle registry and an army officer at the rank of lieutenant colonel.

The commission reconstructed the events of the day from the time he reached office to the time of his kidnap.

The last day

Thursday, September 21, 1972 was a normal working day for Chief Justice Bendecto Kiwanuka, reporting to office at 8:15am. As he settled into his office, his bodyguard, Detective Constable Benedicto Mugalya, sat in the corridor outside the office. Mugalya was one of the witnesses to the commission.

In his testimony to the commission, he said shortly after Kiwanuka had entered his office, three men in civilian clothes approached him, asking for the office of the Chief Justice, saying they were there on ‘official duties’.

He told the commission that as he tried to speak to Kiwanuka’s secretary, the three men forced their way into the office, straight to where the Chief Justice was seated.

Once in the office, he was shocked to see them pulling out pistols, telling Kiwanuka that they were security officers taking him to their offices.

When Kiwanuka asked to know where he was being taken, one of the three men pulled out a pair of handcuffs.

“I went out to call the chief registrar to stop the men from handcuffing the Chief Justice. By the time we came, he was handcuffed and they instead told the chief registrar to be in charge and make sure he locks the Chief Justice’s office as they led him out of the office,” he said.

Kiwanuka slapped

Mugalya further told the commission that while Kiwanuka was being pushed into his kidnappers’ car, he tried to call him to go with them, but he was instead slapped and pushed into the waiting car.

“He was taken in a light blue Peugeot 504 registration number UUU 171, which drove towards Kampala International Hotel (Sheraton Hotel),” he added.

Unfortunately for Kiwanuka, none of the people around could recognise the three men who picked him. That was the last he was seen. As Kiwanuka was being taken away, the chief registrar made several calls to different offices, including the State House.

Witness number 72 was Alfred Iswat, an agent from Special Branch (an intelligence arm of the police). Iswat was assigned by the then acting head of Special Branch Luke Ofungi, to start investigating what had happened to the Chief Justice.

Armed with the particulars of the vehicle, Iswat started from the central registry of motor vehicles.

“The vehicle was registered in the names of Uganda Armed Forces, the stamp which was on the form for transfer of ownership was stamped by the transport officer, Military Police,” Iswat said.

But he observed that the records showed that the vehicle with that registration number was a Volkswagen and not a Peugeot 504, suggesting that the registration number on the vehicle used in the abduction had been switched.

On October 20, almost a month after his disappearance, file number GEF200/72 was allocated to Assistant Inspector of Police (AIP) Joyce Drania Mawa for further investigations.

On October 24, she sent two police constables to the central registry of motor vehicles to access the file of motor vehicle number UUU 171, but they found the file was missing.

AIP Mawa sent the two constables back to the central registry thrice on different occasions: October 26, 1974; October 30, 1974; and November 6, 1974.

Identifying the car

They found no file corresponding to the vehicle registration number in question.

On November 11, 1974, AIP Mawa went to the central registry of motor vehicles where she was given the particulars of the car in question.

The details indicated that it was a Volkswagen saloon car belonging to the Uganda Armed Forces, box number 7069, Kampala.

Witness 42 was Cyprian Nsubuga Kyejusa from the central registry of motor vehicles. He presented to the commission evidence to show that, that particular Peugeot 504 got that number on March 24, 1971 and had been initially registered as USH 351.

Evidence produced before the commission showed that the TR2 forms for number plate UUU 171 read in part: “Uganda Armed Forces of West Mengo district, Kyadondo County, box 7069 Kampala. It is a Volkswagon 1200 saloon grey in colour.”

He, however, told the commission that it was not unusual for two different vehicles being allocated the same number.

“When you come later, you find the number (plate) had already been given to somebody else, whereas the form which you completed reads that it is you who got the number plate.”

The army denied ownership of the car. However, witness number 533, Lt Col Samuel Hannington Nzimuli, a Quarter Master General in the Uganda Army (AU), told the commission that he had no records of UUU 171, saying: “I have tried to search for that record but unfortunately, it does not exist with the Uganda Armed Forces.”

He went on to say: “Well, I am a Quarter Master General of the Armed Forces. I have nothing to do with the Uganda government...what I say is what I have got on the paper, which if you want the Security Council can provide.”

Implicating Minister Kibedi

Sgt Stephen Kintu, Army Number UA 7139, was another witness to the commission. Kintu told the commission of his meeting with the minister in June 1972, near Norman Cinema (currently Watoto Church). He said he drove him to his home for a private conversation.

“He (Kibedi) told me that ‘I want to assign to you a duty to kill Ben Kiwanuka.’ I told him that ‘let me first go back and think about this.’ He put me in the car and took me back to Malire (Lubiri) up to the gate,” he said.

Kintu further said: “He (Kibedi) said the reason why he wanted to kill Kiwanuka was that after the military government had handed over power to the civilians, it was going to be Ben Kiwanuka who was to take over because he had from Democratic Party, people and for that reason Kibedi started working against Kiwanuka.”

The report quotes Kintu’s testimony of what transpired during the second meeting at Kibedi’s home in what he described as a special room.

“In that special room, he said to me: ‘You told me that you had gone to think about it, and now what have you thought about?’ I told him: ‘Sir, I have failed… I cannot manage that work.’ He promised me Shs50,000 if I killed Benedicto Kiwanuka. I told him: ‘I cannot perform that duty,” he said.

Kintu was cautioned not to reveal the aborted mission to anyone saying: “And he told me: ‘As you are a fellow Musoga, I do not want you to leak this information to anybody…I will work with guerillas to do this duty for me….,”he revealed.

From Malire, Kintu was transferred to Mutukula, where he was when the news of the kidnapping of the Chief Justice found him.

He told the commission that he feared for his life, the reason he never reported the matter anywhere.

The commission report calls him a “surprise witness and at the same time, a special witness whose appearance was announced in the news media beforehand…”

Kibedi fires back

Kintu’s testimony was in the news, and the government paper, Voice of Uganda, exonerated the government and implicated the former minister, who had run into exile.

To clear his name, Kibedi, from his exile base in Paris, France, sent an affidavit detailing what he knew about the different disappearances he said were on the orders of Amin.

In regards to Kiwanuka’s disappearance, he stated in his affidavit thus: “I spent the morning of that day at Entebbe, where you were seeing a visiting African minister of foreign affairs.

After the interview with the visitor, I stayed with you for a few minutes for instructions on routine official business. As I rose to go, you said to me: “The boys have got Kiwanuka. They had to pick him up at the High Court because he knew he was being followed, and he was very careful about his movements.”

In his affidavit, Kibedi pinned Amin in the murder, saying Amin went ahead and executed the people who did the actual killing of Ben Kiwanuka to kill evidence, saying: “On or about 25 June 1973, you had two “guerrillas” executed by firing squad after a “trial” by the Military Tribunal. It was alleged that the two men had been found with lists of 64 people to be killed in Uganda,… among those on the alleged list was Benedicto Kiwanuka, the Chief Justice… clearly, the two men were being accused of having murdered the Chief Justice, among other people.”

Conclusion

Weighing the evidence received from the ‘special witness’ Sgt Kintu, as the commission branded him, and Kibedi’s affidavit, the commission, first of all, disregarded Kibedi’s affidavit, saying it was based on rumors.

The commission went ahead to describe Kibedi’s evidence as a pack of lies devoid of tangible facts saying: “The world is only too familiar with the fashion of exiles who will go to any length to discredit and pour ridicule on their home governments and whereas such bilious outbursts and ineffective may find sympathetic ears in the foreign countries whose own news media may either be not so efficient in getting the true account…it gives a totally distorted picture of what happened, we refuse to accept them as the gospel truth just because an exile who happens to be Mr Kibedi says so.”

The report further read: “We have no hesitation in rejecting his statement in as far as it refers to the identity of the perpetrators of the kidnaping of the former Chief Justice and others mentioned by him. But we, however, agree with him when he says in answer to Sgt Kintu’s evidence that it is all untrue. Our assessment of both of them is that neither is better that the other.”

“In the circumstances what is left is that Peugeot 504 in which Mr Justice Benedicto Kiwanuka was taken and which at the time was displaying the number plates of the Volkswagen belonging to the Uganda armed forces. In view of our comments and findings of this particular issue we say again that the former Chief Justice of Uganda was kidnapped by people who must have been known to the authorities having the custody of the Volkswagen and who must also have known the nature of their mission. …… We find that there is a strong probability that he was murdered by those who kidnapped him,” the report read.

The commission and its mandate

The creation of the Commission of inquiry followed pressure from foreign powers after the release of a study report by the International Commission of Jurist. The Jurist report by American Justice David Jaffery Jones, looked into the disappearances of people in the early years of the Amin regime.

Under legal notice number two of June 30, 1974 the commission titled ‘Commission of inquiry into the disappearance of people in Uganda since 25, January 1974,’was created.

It was made up of three members all of them security personnel save for the chairman, who was a justice of the High Court.

The commission was appointed by the minister of defence, who at the time was the president and commander-in-chief, declaring, “ I, as the General Idi Amin Dada, V.C., D.S.O., M.C. and Commander-and-Chief of the Ugandan Armed Forces, also holding portfolio of the Minister of Defense, do hereby appoint the following Commissioners. Mr Justice Mohamed Saied Chairman, Mr S.M. Kyefulumya, Superintendent of Police, member, Superintendent of Police Mr A. Esar member, Captain Haruna of the Uganda Armed Forces, member. And do hereby decree that Mr. C.C. K. Ndozireho, a Kampala advocate, shall be the secretary of the said commission…”

The terms of the commission included, inquiring into the identities of the people who disappeared, circumstances under which they disappeared, establish whether they are dead or alive, for those who fled into exile, the commission was to establish why they did so, for those confirmed dead, the commission was tasked to find the circumstances under which they died, when, where and how.

The legal notice also required the commission to establish “whether there are any individuals or organisations of persons within or outside Uganda who are criminally responsible for the disappearances or deaths of the missing persons and what should be done to the persons criminally responsible for such disappearances or deaths.”

The commission was prohibited from hearing any evidence that was deemed security sensitive. “And I do hereby direct that any matter touching the security of the State shall be excluded from evidence.”

The notice gave witnesses who so wished a leeway to testify in camera, and also gave those whose names were mentioned during the witness testimonies to defend themselves, but not given chance to cross examine those who gave evidence against them.

Though the commission was a public commission, the legal notice provided for some of the witness on the directive of the president to give their testimony in presence of radio and television cameras, “the president may direct that certain evidence be given in public, in the presence of the press, radio and television.

There were some exclusions, however, the commission was not allowed to look into cases of disappearances of persons of Asian origin or extraction.