Prime

Judicial accountability is a vain concept in Uganda

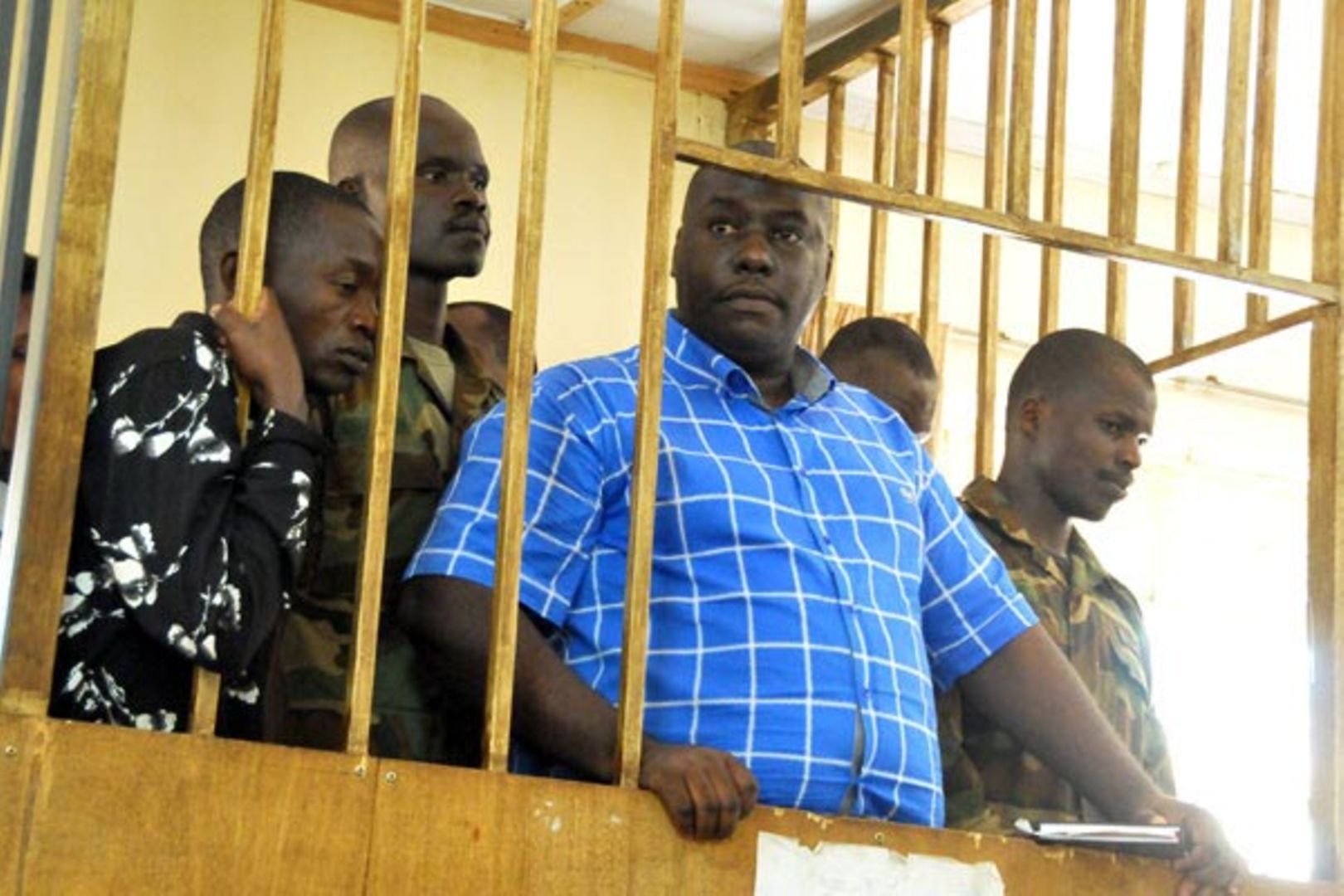

Then Nakawa MP Michael Kabaziguruka (in blue shirt) in the dock at the General Court Martial in Makindye, Kampala in 2016. Kabaziguruka successfully challenged his trial before the Court Martial. Photo/File

What you need to know:

- There should be a reckoning for superior judges and courts. A precedent for this was set by the recent mea culpa of the Kenyan judiciary in their joint communique of February 21, acknowledging their unfortunate past and reaffirming their commitment to constitutionalism and the delivery of justice to the people.

The other side of the coin of judicial independence is judicial accountability. To avert the spectre of tyranny by the judges, their decisional autonomy comes with a duty of accountability to the people on whose authority they exercise judicial power.

Judicial accountability is therefore synonymous with the transformative concepts such as ‘explanatory accountability’ or ‘judging judges’—meaning that the modern judge can be asked by the citizen to give an account as to why they behaved in a particular way. This requires individual judges, and the courts as an institution, to bear the responsibility for actions, policies or decisions that are contrary to constitutional or legal standards.

As our Supreme Court said in Attorney General versus Nakibuule (2018) “…the need for judicial accountability has now been recognised in most democracies …. Judges can no longer oppose calls for greater accountability on grounds that it will impinge upon their independence… judicial accountability should not be undermined. What is critical is that a right balance between the principles of judicial independence and accountability needs to be maintained”.

Underpinning these concepts are the constitutional provisions of the Judiciary. Judicial power is derived from the people and is to be exercised in the name of the people and in conformity with the law, the values, norms and aspirations of the people. Judges are required to ensure justice to all irrespective of their social or economic status, without delay and guaranteeing adequate redress for legal injury (Article 126).

A person is entitled to a fair, speedy and public hearing before an independent and impartial court or tribunal (Article 28). The courts must also observe all the national objectives and directive principles of state policy. This is the basis on which judicial conduct may be judged.

According to the World Justice Project, Uganda’s rankings in both civil and criminal justice have declined since 2015. Uganda is presently ranked at the 115th position out of 142 countries in the civil justice category, and 119th in the criminal justice category. The rankings are decidedly worse in regional rankings.

Below we highlight a few contemporary issues that would have been resolved by cases mired in the judicial system. The cases show that although the Ugandan citizenry was happy and quick to entrust the Judiciary to address their various grievances, the Judiciary has consistently betrayed the trust of the people and is clearly wanting in accountability.

Trial of civilians in the court martial

In Attorney General versus Michael Kabaziguruka (Supreme Court Civil Appeal No 2 of 2021), the legislator successfully challenged his trial before the Court Martial. The Constitutional Court, after a five-year delay, declared that his trial and that of other civilians in the court martial were unconstitutional.

The Attorney General appealed and obtained a stay of the Constitutional Court decision. Submissions in the appeal closed in 2021 and judgment has since been pending. Last month, the top court summoned the parties to attend a scheduling conference. The embarrassed parties had to remind the court that judgment was long overdue.

Meanwhile, it took the Constitutional Court seven years to rule on the earlier case of Captain (rtd) Amon Byarugaba and 169 other civilians who had been trapped in the Court Martial system since 2002. After suffering extremely lengthy and unfair trials and sentences of imprisonment, the group sued the Attorney General in Constitutional Petition No 44 of 2015. In December 2022, the Constitutional Court ordered their removal from the Court Martial, among other remedies. A notice of appeal was promptly filed by the Attorney General. The memorandum of appeal has never been filed, more than a year later. Even if the appeal is filed, heard and decided this year, many of the intended beneficiaries would already have completed terms of imprisonment longer than 10 years.

The delayed disposal of the Kabaziguruka and Byarugaba cases is the reason why National Unity Platform’s Olivia Lutaaya and her 31 co-accused have been languishing in the Court Martial for the last four years.

The missing Pinetti Lubowa Hospital

In Initiative for Social Economic Rights versus Attorney General (Constitutional Petition No. 7 of 2019), a right to health campaign group promptly sought the nullification of the Pinetti Lubowa Hospital agreements for having been concluded in breach of public finance and public participation provisions of the Constitution. Submissions were closed by February 2022. Two years later and $156m (Shs603.1b) disbursed to Ms Enrica Pinetti, there is no judgment and no hospital. The case has been pending for five years.

Privacy-infringing electronic number plates

In Legal Brains Trust versus Attorney General (Court of Appeal Civil Reference No 7 of 2023), democracy and human rights watchdog seeks an injunction to stay the implementation of the new number plate system, pending a determination of its legality. The High Court took two years to dispose of the injunction application, by dismissal. Another application was filed in the Court of Appeal in July last year and has never been fixed by the court despite several reminders.

On November 15, 2023, while presiding over the pass out ceremony of police and immigration officers at Kabalye Police Training School in Masindi, President Museveni declared: “I am now insisting on the electronic number plates. Please, I want my number plates. Don’t delay my number plates.”

The case will mark its fourth anniversary this year as the courts continue to shy away from scrutinising the President’s keystone security project.

Abusing criminal justice through piecemeal trials

The cases brought by and against Mr Godfrey Kazinda are too many to list here. Mr Kazinda, a former employee of the Office of the Prime Minister, was implicated in a slew of financial crimes more than a dozen years ago.

After a six-year delay, he obtained judgment in his favour in Constitutional Petition No 30 of 2014 which had challenged the DPP’s misconduct of orchestrating against him an endless series of piecemeal prosecutions arising from the same events for which he had already been charged or convicted.

In August 2020 the Constitutional Court found that this was an insidious breach of the rule against double jeopardy and ordered the Anti-Corruption Court to immediately discharge Kazinda in all pending criminal cases and any future cases whose offences are found on the same or similar facts, and could have been prosecuted at once in the original trial.

Unfortunately, even this reprieve from the prosecutorial abuse not only came too late for the beleaguered accountant (after he had completed serving a quashed five-year term of imprisonment) but has also been stayed by the Supreme Court pending the conclusion of a three-year-old appeal whose timelines are anybody’s guess.

The State is therefore continuing to torment him with the forbidden piecemeal prosecutions.

Justice delayed is justice denied

The case of Henry Karimpa versus Attorney General (East African Court of Justice Appeal No 6 of 2014) well demonstrates the high cost of a delayed judicial resolution.

Although the appellant was successful in getting a decision that the Ugandan President’s award of the Karuma dam construction contract to a handpicked contractor was done in violation of Ugandan law and under the East African Community Treaty, the court was unable to give a helpful remedy. The court found that it was impractical to reverse the construction of the dam. It was a fait accompli (a thing that has already happened).

The delayed resolution of cases involving citizens seeking protection from the excesses of government and its favoured corporations means that the Judiciary has become an accomplice to the abuser of the citizens’ rights.

The nation’s top judges behave like the surgeon toying with his scalpel, in the stench of putrefaction. But even when the judicial scalpel is eventually applied, the Attorney General now invariably applies for a stay of the belated judicial interpretation rendered. Soon the stench disappears, like that of roadkill bleached by the harsh tropical sun.

The legality of an indefinite stay of the judicial interpretation of a given law is also doubtful. Kenyan courts have found such requests by the government perverse on the simple basis that the judiciary is bound to protect the citizen from irreparable injury pending the conclusion of its scrutiny of the challenged law. In compensation, they expedite appeals involving sensitive interpretations of law.

As applied to the civilians in the court martial, application of the Constitutional Court decisions would strictly mean that those trials would be transferred to the civilian courts.

There is no legal justification that makes it an absolute necessity to try NUP’s Olivia Lutaaya and her 31 co-accused civilians in the court martial for offences of treachery and being possession of ammunition, while Jamil Mukulu, the suspected former commander of the Allied Democratic Forces, a banned organisation under the Anti-Terrorism Act, is being tried in the civilian courts.

The wider deleterious effects of delayed justice must be spotlighted. There is the litigant desperate for justice who will seek to jump the queue to have their case heard on an expedited basis. When faced with counsel who cannot guarantee a prompt hearing or even a simple hearing date, such litigants find audience with often willing judicial officers leading to probable impropriety and corruption.

The triple calamitous effect on counsel as the foot soldier of justice, financially, physically and mentally is untold. The inability of counsel to achieve his ideals in the pursuit of justice, worn ragged with the exhaustion of unending trips to court, harassed by the judicial officer unwilling to be dragged into a probable confrontation with the State, continually shame-faced before the client, and yet still challenged to put bread on the family table and probably pay the rent for home, office or both.

What must happen next

There should be a reckoning for superior judges and courts. A precedent for this was set by the recent mea culpa of the Kenyan judiciary in their joint communique of February 21, acknowledging their unfortunate past and reaffirming their commitment to constitutionalism and the delivery of justice to the people.

It is time the Uganda Judiciary accepted responsibility for a de facto breakdown in the checks and balances envisaged by the Constitution where the Judiciary is meant to protect the citizen against the actual or threatened wrongdoing of the political branches or the rich and powerful.

It is a requirement of the Constitution and Uganda Judiciary Code of Conduct to expedite the hearing of constitutional matters and deliver judgments within 60 days.

In the age limit case (2018), the constitutional petition and appeal were both completed in less than a year after the challenged law was enacted. The Constitutional Court removed itself from the hustle and bustle of the capital city, and sat at night and over the weekends, to ensure speedy justice.

Dr Busingye Kabumba’s case challenging the appointment of judges in an acting capacity was concluded the same year it was filed. The petition challenging the Anti-Homosexuality Act 2023, like its 2014 precursor, has also been heard on expedited basis. This betrays a double standard in the prioritisation of cases by the nation’s superior courts.

The courts can move fast and deliberately when they wish to. How the courts presently determine the ‘sensitivity’ of cases is suspicious and gives an apprehension that the independence of the Judiciary is being interfered with by the Executive.

The Judiciary must shed the tortoise shell and pick up its running shoes before it is too late. It must radically transform its subpar case management practices, especially in the appellate courts and being to deliver the constitutional guarantee of speedy hearings and effective remedies to all the people of Uganda, not just Executive or the chosen few who happen to compromise the ruling elite.

Compiled by Ladislaus Rwakafuuzi, Mohmed Mbabazi, Peter Mukidi Walubiri, Edward Kato Sekabanja, Daniel Walyemera, Julius Warugaba, Peter Arinaitwe, William Muhumuza, Ivan Bwowe, Eron Kiiza, Lillian Drabo, Anthony Odur, Sam Ssekyewa, Humphrey Tumwesigye, Phillip Karugaba, & Isaac Ssemakadde.