Prime

How Museveni outfoxed Wilson Wamimbi of Abamasaaba

Mr Muniini K. Mulera

What you need to know:

Thank you, my brother Wamimbi, for being a good friend, a great example of dignified endurance against provocation, and a true Ugandan patriot

Dear Tingasiga:

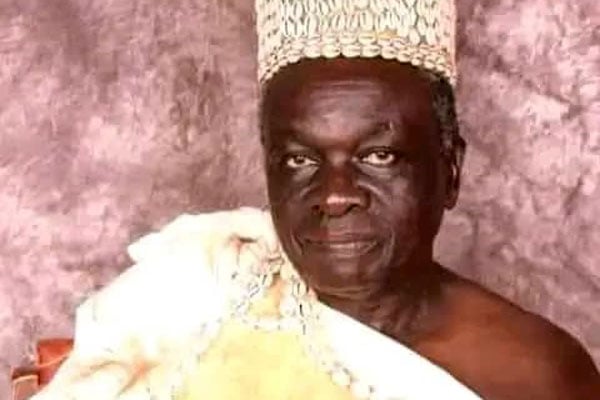

We are saddened by the death of Wilson Weasa Wamimbi of Bugisu, which occurred on Friday April 12. His family has lost their patriarch. The Bamasaaba have lost their first Umukuuka of Inzu ya Masaba. I have lost a friend.

The eulogists will rightly focus on his role as the first cultural leader of the restored Inzu ya Masaba (House of Masaba), a role he performed very well from 2010 to 2015. The historically accurate will point out that he was the second cultural leader of Abamasaaba. The first, whose title was Umuinga of Bugisu, was Yonasani Buyi Mungoma, who was elected in 1963 and lost his job when it was abolished by the Republican Constitution on September 8, 1967.

As I reflect on our friendship, on our personal conversations, on the confidences he shared, and on his political career, the consequence of Wamimbi’s choice to join President Yoweri Museveni’s political team strikes me as one of the most important lessons that he has left behind for those who are actively engaged in survival politics in Uganda.

Wamimbi was one of the most formidable political opponents of Museveni and his National Resistance Movement (NRM) in the late 1980s and early 1990s. As Local Council V chairman of Mbale District, Wamimbi’s political skills and machine had become an impenetrable fortress that had denied Museveni and James Wapakhabulo any hope of taking control of Bugisu. With looming presidential and parliamentary elections in May and June 1996, respectively, Museveni launched a brilliant offensive in which he outfoxed Wamimbi and effortlessly neutered the great man.

Museveni, always way ahead of his opponents, made Wamimbi an offer that he knew that the latter would not refuse. If Wamimbi joined Museveni’s team, the president would appoint him an ambassador of the Republic of Uganda. Visions of becoming a major player on the national stage, a member of the inner circle with access to the president, an honoured envoy rubbing shoulders with international power brokers, and the fabled lifestyle of the diplomat were swirling in his head when he took the bait. He happily joined Museveni and, like Enoch, the son of the snake priest in Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart, Wamimbi became “the outsider who wept louder than the bereaved.”

Presently, he delivered Mbale and Bugisu to Museveni and Wapakhabulo, and awaited his reward. He arrived in Ottawa, Canada in the Winter of 1997, to take up his new appointment as His Excellency the High Commissioner of Uganda to Canada. There was no honeymoon period, for he walked into a frigid nightmarish environment that nearly broke this good man who had surrendered his political powerbase.

He moved into the high commissioner’s residence at 235 Mariposa Avenue in Rockcliffe Park, an upscale district in Ottawa that is one of the finest and most expensive neighbourhoods in Canada. The house was in disrepair, with dysfunctional amenities. There were periods without electric power or telephone service because of unpaid bills. Delayed arrival salaries was the norm.

Over at the chancery, located at 231 Cobourg Street, Ottawa, which served as the main office of the high commission, Wamimbi felt unwelcome. Some political appointees, who had been active in the political struggle against Milton Obote’s UPC government in the early 1980s, allegedly refused to accept Wamimbi as their superior. Some claimed personal friendship with powerful people at State House and saw no reason to subordinate themselves to the newcomer to the NRM whose loyalty to the appointing authority was suspect.

Wamimbi called me a few months after his arrival in Canada to introduce himself to me and to seek my help in the civil war that had engulfed the high commission. Someone had erroneously told him that I was influential in the Uganda Government, and that I could also mobilise support for him among Ugandans in Canada. I disabused him of these notions but assured him of my willingness to mediate if I could, and advise him, upon his request, on how to navigate his way through Canada.

We began regular telephone conversations, during which I warmed up to him, and formed the impression that he was a very intelligent man who now realised that he had made a serious political miscalculation for which he was rewarded with a most unsatisfying appointment, and the humiliation and misery of a severely dysfunctional office.

In June 1997, Wamimbi called me with a question that left me depressed. “Is it true that Museveni is coming to visit Toronto?” the president’s ambassador asked me. I had heard about the president’s planned visit, but I was not aware of the arrangements that had been made for him. Wamimbi confirmed the report, and called to inform me that he understood that the president’s itinerary, logistics and security would be handled by the State House and the Government of Canada. The Uganda High Commission would have no significant role to play, if any.

The irrelevance of the high commissioner was evident at a gala dinner for the president, organised by the Ismaili Community in Canada, to which my wife and I were invited. Museveni did not show up for the event. Wamimbi was largely ignored, his presence only acknowledged as an afterthought. Instead, Richard Kaijuka, who was a cabinet minister at the time, was delegated to stand in for the president.

The experience erased Wamimbi’s illusion of power and hopes of influence in his role. The civil war in his office escalated. And the financial challenges at the embassy compounded the situation. Wamimbi soldiered on until his tour of duty ended. He returned to Uganda and secured appointment as resident district commissioner (RDC) for Iganga District. It was a welcome climb-down, albeit inadequate to heal the self-inflicted wounds of misplaced expectations to be part of a ruling house to which he never belonged and could never belong. After a short stint as RDC, Wamimbi won the election to become the first Umukuuka of Inzu ya Masaba. I received the news with joy. Abamasaaba had chosen a worthy leader. My friend’s humiliation had been eased by the honour. However, he would not be the last victim of blind ambition and succumbing to trickery with political candy.

Thank you, my brother Wamimbi, for being a good friend, a great example of dignified endurance against provocation, and a true Ugandan patriot. Let the celebratory drums and songs be presented. We join the celebration of your life of service and your sincere desire to advance the interests of Bamasaaba, not just yours alone.

Muniini K. Mulera is Ugandan-Canadian social and political observer