Ojiambo’s half century as a marine engineer

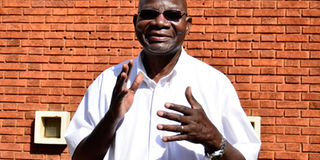

Aggrey Mbulu Ojiambo during the interview. Below Ojiambo in 1973. PHOTOS BY ABUBAKER LUBOWA/FILE.

What you need to know:

Sailing the TIDE. Aggrey Ojiambo Mbulu spent five decades at sea, ensuring safety of marine vessels. He talks to, EDGAR R. BATTE about his career.

Soft-spoken. Unassuming. Brilliant. Three words aptly define marine engineer, Aggrey Ojiambo Mbulu. He grew up to realise his childhood dream.

He always wanted to become an engineer and studied with this aspiration in mind. As a boy, seeing men in overalls drew his curiosity. Then, seeing them fix buses that had broken down, excited him. It did not matter that the men were dirty, with stained clothes.

They were liberators in their own right; saving travellers whenever a vehicle had developed mechanical problems. In 1969, the defunct Eastern Africa National Shipping Line (EANSL) made a call for O- and A-Level leavers to apply for a training opportunity as cadet engineers.

More than 100 applicants expressed interest. Ojiambo was one of the four who were shortlisted. The youngster who had just sat for O-Level exams at Bukedi College Kachonga, recounts confidently responding to questions in front of a panel of interviewers who nodded in approval.

Leaves for school

On being taken on, he was asked to travel to Nairobi for an introductory course in marine engineering at Kenya Polytechnic College. On the flight from Entebbe to Kenya’s capital city, Ojiambo was as joyful as anyone starting the journey of their dreams can be.

He was on course to start the training that would see him technically man some of the world’s biggest ships from Africa to Europe-where the EANSL did a lot of intercontinental trade.

“As a marine engineer cadet studying at the Kenya Polytechnic, I, on ‘sandwich basis’ served in a trainee capacity under instruction of ‘ship foremen’ at the then East African Railways and Harbours’ main engineering workshops at Nairobi and under senior marine engineers at shipbuilding yards,” Ojiambo explains.

Later on he worked onboard foreign deep seagoing vessels, in line with the East Africa Marine Engineer Cadet Training Scheme tailored by the Merchant Navy Training Board of the United Kingdom.

The workshops, shipyards, and onboard ship training periods provided exposure to practical situation industrial experiences for the youngster while he attended initial Applied Engineering Sciences and introductory Marine Engineering professional classes at the Kenya Polytechnic.

Full attendance and satisfactory college results were a prerequisite to admission to Advanced Marine Engineering courses taught at UK maritime colleges and he excelled in the studies.

“In the fourth year of study in Nairobi, I was relocated to the UK for a core course at Hull College of Higher Learning for 18 months. The learning was both theoretical and practical, with workshops and laboratories,” Ojiambo recollects.

He holds a UK Marine Chief Engineer Certificate of Competency (COC) certified by the Government of the Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, issued by Her Majesty’s Coast Guard and Maritime Agency.

He explains that the attainment of the COC was a result of intensive academic and professional training that he received, particularly in maritime colleges in the UK. He was one of the best students in class. He recounts incidents during the course when he was asked by lecturers to help out other students with concepts that they found hard to grasp.

The training had a practical experience in a number of industrial setups, such as ship design and building yards; marine and general engineering workshops and laboratories; and onboard deep sea merchant navy and special purpose vessels.

“The exposure helped me appreciate what makes a marine engineer,” he adds.

Work

The company was glad to give him a job as a junior engineer. His duty was to observe and log engine room operating parameters for evaluation by senior engineers.

“I also carried out maintenance tasks such as engine services/repairs onboard, strictly under supervision of senior marine engineers whose guidance impacted me with practical skills that helped advance my career.”

His meticulous track record earned him a promotion to a senior engineer, in which capacity he served on board various deep seagoing ships including MV Jitegemee, a general cargo vessel of 11,200 BHP, at the senior rank of third engineer, charged with ensuring efficient and safe operation of the ship’s propulsion, electrical and steam generation plants. He was in charge of engine room watches, taking corrective actions in consultation with the vessel’s chief engineer.

Colourful career

Forty-eight years on, Ojiambo looks back to a fulfilling career. Between 1970 and 1980, he underwent training sponsored by EANSL at its headquarters in Dar-es-Salaam, Tanzania. Between 1981 and 1983, he joined the traditional civil service employment as marine engineer and then worked with Ministry of Regional Cooperation, based at then Uganda Fresh Water Fisheries Research Organisation (UFFRO), now National Fisheries Resources Research Institute (NAFIRRI).

For 20 years, from 1983, he was employed as a marine engineer at Uganda Railways Corporation (URC), with an additional three years as a consultant, until 2006. He chose to retire but was asked to be re-employed as an engineer in the same company.

When he first joined URC, he was first engineer on railway wagon ferry MV Kaawa for nine months. He was then promoted to chief engineer for a sister vessel, MV Kabalega. He occasionally served in that capacity on MV Pamba and MV Kaawa too.

As first engineer, his duties were majorly vessel maintenance with the objective of ensuring efficient and safe operation of propulsion and other machinery/systems onboard. He also supervised structural and machinery repairs in dry dock as well as scheduled and called engine overhauls; all done with due consideration of safety of crew, vessels, cargo, and the environment.

“As a chief engineer, I would also liaise with the ship captain on general technical matters affecting the vessel and continuously sensitised the engine room crew through departmental meetings,” he further explains.

While at NAFIRRI, he was in charge of maintenance of all the ministry’s marine research crafts, mainly bottom fishing trawl boats.

“I worked closely with marine biology research scientists in planning and scheduling research trips on lakes Victoria, Kyoga, Albert, Edward and on other inland water ways such as River Nile and River Ssezibwa. It was my duty to ensure safe and efficient operation of marine research crafts and their equipment, through regular inspections and adherence to applicable safety standards,” Ojiambo adds about his career highlights.

In 2011, he returned to URC, employment as a marine engineer to help with concession monitoring. He also represented URC on various technical committees of the Ministry of Works and Transport (MoWT).

He also participated in the supervision of the works undertaken by Southern Engineering Company Ltd (SECO) contracted by the MoWT for the rehabilitation and upgrade of MV Kaawa and the ship building and repair facility – the Floating Dry Dock (FDD), both at Port Bell.

In February 2015, URC staff, under the engineer’s supervision, carried out a dry docking operation that delivered the Bukakata-Luuku ro-ro ferry operated by Uganda National Roads Authority (Unra) into the floating dry dock at Port Bell. The ferry has since then been in dry dock undergoing major repairs and upgrade undertaken by a firm contracted by Unra. A reverse process (un-docking) will be carried out once again by URC staff as soon as the works are complete.

Recognition

For his exemplary service to Uganda, he was recognised by President Yoweri Museveni with a national medal at the International Workers Day celebrations of 2016.

Now in his retirement, Ojiambo offers consultancy to clients such as Consolidated Marine Contractors, Mombasa. “The consultancy involves, designing of civil works and new ships. This is in addition to my normal duties as a marine engineer in charge of maintenance of the corporation’s marine assets (such as floating dry dock and wagon ferries),” he explains.

His advice to young people is to take up available opportunities to undergo training in this noble profession.

“This profession is noble for what it contributes to the world and national economies,” he concludes.

Memories at sea

* The longest voyage I undertook was from Mombasa to Antwerp, a major seaport of Belgium, going around the cape. I was on the voyage as engineer cadet freshly from college to undergo scheduled industry training, onboard MV Uganda. The 32-day voyage was also the longest time spent at sea on a single voyage.

* During my seafaring days, it was exciting visiting the world’s largest modern seaport cities such as London, Hamburg, New York, and Singapore. It was enjoyable having interactive moments with people of various nationalities across the world, some language barriers notwithstanding. On a domestic note, meals and general living conditions onboard vessels were five-star hotel standards.

* Seafaring is a business for those who can keep their calm while acting swiftly in situations of distress such as grounding or fire. During my first voyage, a fire broke out in MV Uganda’s engine room. It raged on for two days before it was put out by teamwork of all onboard with everyone performing his part as assigned by the vessel’s muster plan – the roles chart displayed at assembly points and mandatorily practised through regular drills. That was an incident to remember forever.