When MPs debated to have Obote, Amin implicated in gold scandal

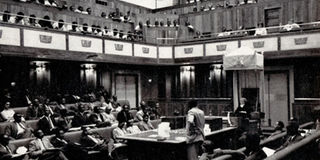

Parliament of Uganda in session in the 1960s. In February 1966, Mityana MP Daudi Ocheng tabled a motion calling for the implication of ministers as accomplices in the looting of gold. FILE PHOTO

On February 4, 1966, former UPC secretary general John Kakonge, while opposing a motion brought by Mityana Member of Parliament Daudi Ocheng implicating ministers as accomplices in the looting of gold, cautioned that “I can see with my mind’s eye troubles knocking at the door and tragedies threatening to swallow all of us up.”

Unfortunately, his fellow MPs did not take heed and voted for the motion. A few months later, the troubles that were forming in his “mind’s eyes” were upon the country and, as he had predicted, they paid with their lives and properties.

The Constitution was abrogated, kingdoms were abolished, ministers arrested and Uganda’s first president, though ceremonial, was forced into exile. From there on, dictatorship and the rule by the gun defined Uganda’s politics.

How it began

The alliance between Uganda Peoples Congress (UPC) party and Kabaka Yekka (KY) was like mixing water with oil. Barely two years after independence, the coalition could no longer hold and it was a matter of time before it fell apart.

When Buganda lost the 1964 referendum on the counties, there was no looking back. War drums had been sounded. There were alleged counter schemes by both the central and Mengo governments, each planning to outdo the other.

Factions within the central government and military allied to Mengo were created, coup plans made and the central government also planned the same.

When the gold scandal broke and the motion calling for the suspension and investigation of Col Idi Amin’s activities was moved, this kicked the existing factions into action.

When allegations of gold, coffee and ivory being looted from DR Congo by the Uganda Army under the command of Amin and the training of a private army with the purpose of overthrowing the Constitution were made, government promised to have them investigated and the report made public.

As the majority party in Parliament, UPC had agreed not to discuss the motion of Amin’s conduct. In his 1965 motion, Ocheng wanted Amin suspended, saying: “Because of this plot and loot, Amin had been assured he would be the army commander of Uganda Armed Forces.”

With his party’s firm control over the House and with the assumption that the entire Cabinet was behind him, Obote in January 1966 went on an overdue tour of northern Uganda.

His absence from the seat of power gave the Mengo allied factions both in the army and Cabinet chance to reintroduce the motion and have it discussed.

Writing in the book, Uganda Crisis, Akena Adoko says the Cabinet meeting to reverse the earlier decision was Muteesa’s advice to Grace Ibingira, who was then minister of Justice.

“Let us join forces right now. Obote and ministers loyal to him are all out, you are the Cabinet boss, let Cabinet meet now and reverse the decision not to support my motion. This has given me much pains. You and I can do wonders working together,” Muteesa was reported to have said.

Ibingira, who was already known to be an ally of Sir Edward Muteesa, made sure on February 4, 1966, the motion was tabled again by Ocheng. Before Ocheng took to the floor to table his motion, Cuthbert Obwangor moved a motion seeking to suspend the standing orders to allow a marathon sitting until all the business was completed without a break.

In his presentation, Ocheng said: “Mr Speaker, if I live 100 years, or for a 100 hours only, this motion shall always be my greatest contribution to my country Uganda.”

He went on to call for Amin’s suspension and that the investigations by police be made public.

The call for Amin’s suspension was based on Ocheng’s discovery that Amin had deposited Shs340,000 (equivalent of Shs89 million today) on his personal account within 24 days of February 1965.

Besides Amin, Ocheng also implicated prime minister Obote, ministers Felix Onama and Adoko Nekyon for having benefited from the loot.

He also accused Amin, Obote, Onama and Nekyon of plotting to overthrow the Constitution.

“This Colonel Amin figures predominantly in a coup plan to overthrow the Uganda Constitution by government ministers already mentioned above. He is engaged in training 70 youths in a forest for this dangerous venture.”

Gesparo Oda, an MP from West Nile, seconded the motion, saying: “Amin is a scapegoat, a mere tool for bigger guns whom this motion must embrace.”

Abu Mayanja, like Oda, believed it was not Amin on trial, but the integrity of the country’s leaders in general.

“I call for an inquiry, a judicial inquiry into the very conduct of Uganda’s prime minister and of two of his ministers. They will be found innocent, but our people, Ugandans, would have had the proof they need that the Uganda government is quite honest and decent,” Mayanja said.

Ibingira, who was then Justice minister, wanted the motion to have Amin suspended passed, but not on grounds of the gold loot alone.

According to the Uganda Argus of February 5, 1966, he said: “Allegations of gold loot we do not treat seriously. We are all tired of that.

But the other allegations of a plot to overthrow Uganda’s Constitution is indeed very serious, its truth or falsity I am not sure of either. It is, therefore, only right that an investigation to expose their falsity or establish their truth be carried out.”

Ibingira’s change of tone gave credence to the pro-government supporters who believed that the Mengo allied faction in the government wanted Amin away from office to go ahead with their coup plans. Amin was seen as a stumbling block.

Against the motion

The pro-government side present during the debate put up a spirited fight, with Defence minister Felix Onama, who was among those mentioned by Ocheng, taking the lead.

Lango Member of Parliament Martin Aroma was one of the legislators who opposed the motion, asking whether a person of authority can overthrow himself from power.

“It’s against nature to train your own enemies to enable them kill you,” argued Aroma. “If a premier is tired of leading the government, why should he not just resign? Mr Speaker, I am very pleased by this motion, it has showed us those of us who are foxes in sheep skins.”

The Defence minister then dared Ocheng to repeat his allegation outside Parliament where he had no immunity.

And true to his word, when Ocheng issued a statement through the Uganda Argus newspaper with the same allegations, Onama later sued and the East African Court of Appeal awarded him huge compensation for libel.

When Onama took to the floor, he said: “Rubbish, pit-latrine talk is Ocheng’s dirty habit… In my mind, I am certain Ocheng needs a psychiatrist to give him thorough treatment for he suffers seriously from disease of the mind in which he mistakes for truth, imagination and dreams.”

Then Foreign Affairs minister Sam Odaka asked Ocheng to desist from false corruption allegations, or else it could lead to change of government.

“Go ahead Mr Ocheng, ply well this tough trade of yours. Charge a few more ministers of corruption and bribery… that would be the very time to change the government at once.”

It was during the same debate that the unfortunate future to befall the country was predicated. And it came from the least expected person, former UPC secretary general John Kakonge.

The Uganda Argus newspaper quotes Kakonge saying the motion was devoid of clarity. He says it was meant to charge Amin as earlier tabled in 1965, but when returned to the House it was charging the prime minister and two other ministers.

“Mr Speaker, the debate is of the lowest standard, rumour, hearsay and falsehoods are being aired from this very House. I can see with my mind’s eyes troubles knocking at the door and tragedies threatening to swallow all of us up. Implementing this motion is not solution at all… Mr Speaker, I do beg to oppose the whole motion,” Kakonge said.

Despite their efforts to block it, by punching holes in the credibility of the motion mover, they lost when it was put to vote.

The Defence minister, who was to implement what the motion demanded, had no legal basis under which he was to suspend the colonel and instead on February 5, he sent Amin on leave instead of suspending him.

Then Internal Affairs minister Basil Bataringaya also followed through and under the Commission of Inquiry Ordinance Cap 37 of 1951, appointed a commission to inquire into the allegations.

Next week about the findings of the commission and their recommendations