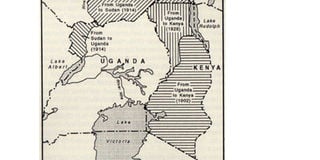

When part of eastern Uganda was transferred to Kenya

On April 1, 1902, the process to transfer the Eastern Province of Uganda to the East African Protectorate (Kenya) was started.

The area in question lay approximately between the present eastern frontier of Uganda and a line running northward from a point where the boundary between British and German territory crossed longitude 36° east and turning north-east.

It included, according to H. B. Thomas, a historian of Uganda, in the 1935 edition of the Uganda Journal, “lakes Naivasha, Elmenteita, Nakuru and Baringo in the Uganda Protectorate before veering gradually north again to follow the line of longitude 36° 45’ east”.

In an article in volume 21 of the Uganda Journal of 1957, Kenneth Ingham, a former professor of history at Makerere College, says the interesting feature of the whole affair was the fact that Henry Charles Keith Petty-Fitzmaurice, the foreign secretary and Marquess of Lansdowne, preferred to act upon the advice of Sir Clement Hill, a foreign office official, instead of accepting the recommendations of so experienced a man as Sir Harry Johnston, special commissioner in Uganda.

Idea mooted

A number of factors fuelled the idea of transferring the territory to present day Kenya, including the 1897 to 1899 mutiny of some Sudanese soldiers in the Uganda Protectorate and the January 27, 1989, critical letter in the Weekly Times Newspaper of London by Col Trevor Ternan.

The colonel criticised the foreign office for not treating the two colonies – Uganda and the East African Protectorate – equally. Following Ternan’s letter, Sir Harry Johnston was appointed as a special commissioner charged with reorganising the administration of the two protectorates.

One of Johnston’s responsibilities was to find an administrative capital for both Uganda and the East African Protectorate, having in mind that the two would be merged at one point.

At the time the seats of administration were at Entebbe for Uganda and Mombasa for the East African Protectorate. In his earlier submission, Johnston suggested that the capital of the two should be located at mile 475 along the Uganda Railway in the Mau Plateau.

In his July 10, 1901, submission about Uganda to the new foreign secretary, Johnston campaigned for the closer union between the two protectorates.

“Upon their interdependence and the close similarity of their interests he said, nevertheless, that he did not propose their immediate and absolute fusion.

Nor, for reasons connected with the distribution of the various tribes, did he recommend any change either in the direction of extending the rule of Mombasa west of its existing limits or the rule of Entebbe over any part of the East Africa Protectorate,” Ingham says.

“Instead of changing provincial or district boundaries he recommended that the two commissioners ordinarily residing at Entebbe and Mombasa should continue with their existing functions, but, in addition, there should be a high commissioner who should have supreme control over the policy and finances of the two protectorates or of the fused protectorate.”

In Johnston’s push for the fusion of the two colonies and having a common capital which was to be the seat of the high commissioner, he went on to even propose the capital for the new unified territories near mile 497 on the Uganda Railway to be called King Edward’s Town.

He went on to say, according to Ingham, “the headquarters of a rule which would stretch from Kismayu and Mombasa to Gondokoro and the Semliki. Here, and not at Zanzibar, which knows nothing of the affairs of Inner Africa.”

Possibility of a federation ruled out

However, the scheme did not materialise because of the intervention of Sir Clement Hill, then superintendent of the African Protectorates.

After a tour of the two colonies, Hill returned to England and in his May 14, 1901, submission to the Marquess of Lansdowne agreed that the weak link in the two colonies was the existence of His Majesty’s diplomatic representative in Zanzibar.

He ruled out the possibility of a federation between the two colonies arguing that “Uganda’s communications were not yet adequate to enable one man to supervise so large an area effectively.”

And Uganda, in Hill’s opinion, would probably look increasingly towards the Sudan.

Having watered down the idea of a federation, Hill proposed the redrawing of the boundaries of the two colonies. His argument was to cut on the cost of operation on the side of Uganda.

“The new boundary should start at a point on the shore of Lake Victoria a little north of Kisumu and should run north-east along the crest of Mount Elgon until it joined the Turkwell River (River Turkana) which it would then follow northward,” he suggested.

The reason behind his idea was to put the administration of the territory covered by the Uganda Railway under a single administration.

War of words

A protracted war of words between Hill and Johnston then ensured. Johnston wrote a memo to the colonial office against the idea of adding part of Uganda to the East African Protectorate on the basis of tribes.

“The transfer of Uganda’s Eastern Province would involve the severance of the tribes of that area from their natural focus in Uganda,” he said in the memo.

“Placing the whole railway under one administration, surely that was admirably covered by the idea of a central government at Mau.”

However, during a meeting in the foreign secretary’s office on August 10, 1901, it was agreed that Hill’s decision would be taken to have a territory of Uganda transferred to the East African Protectorate.

Sir Charles Eliot, then commissioner of the British East Africa, agreed with the idea of having a federation, according to a June 10, 1901, communication from Eliot to the foreign secretary.

However, the foreign secretary went ahead to inform the commissioner in an August 26, 1901, letter that he was in favour of transferring the territory east of Mt Elgon to the East Africa Protectorate with a view of improving the administration of the British possessions in East Africa.

Meanwhile, conversations between the Eliot, Johnston and the foreign secretary went on as they waited for the commissioner’s response over which decision was best for the administration of the territory.

It was during these conversations that Johnston realised that his arguments were making little impression on Lansdowne.

According to the foreign secretary’s minutes of November 8, 1901, Lansdowne said: “I don’t think there is really anything in this to stand in the way of the transfer of the Eastern Province. But let us see what Sir Charles Eliot says in the reply to my telegram.”

In reply, Eliot supported the transfer of Ugandan land but did not totally rule out the future federation of the territory.

He approved the scheme for the transfer of territory as far as it went, mainly on the ground that it would force the East Africa Protectorate to take a greater interest in the interior and in the affairs of Uganda and, thereby, pave the way for the unification of the two protectorates.

Deal sealed

In the national archive record of March 5, 1905, Hill’s scheme of transferring Uganda’s eastern province territory to the East African Protectorate (Kenya) was adopted.

However, it was adopted, according Ingham, on the ground that it was only a transitional stage which in due course would lead to the federation of the two protectorates.

The responsibility of redrawing the eastern boarder of Uganda fell on C. W. Hobley who was the first colonial officer in Kenya.

However, in the process of doing so he encountered a number of problems, with the division of tribes being the topmost.

In the book A history of Uganda Land and Surveys by H.B. Thomas and A.E. Spencer they say, “the rites of the divorce of the old Eastern Province from Uganda, and the settlements on her remarriage to East Africa were conducted at the end of November at Njoro.”

Amin ignites debate

During the opening of a self-help mobilisation scheme in Lotuturu in Kitgum District on February 14, 1976, former president Idi Amin declared his desire to have the part of Uganda which he described as the most fertile back.

He went on to tell those present that Uganda’s borders were beyond Juba and Torit in the Sudan. Amin also had a book titled The Shaping of Modern Uganda and Administrative Divisions published in 1976.

In the publication, he said: “I will be providing geographical and historical facts as documented by the British colonial administration on the transfer of Uganda’s lands, thereby affecting its boundary.”

“In stating this, I had in my possession a document indicating that with the appointment of Sir Harry Johnson, the British government gave a clear mandate for this special commissioner to arrange and reorganise the internal administration of Uganda, including its external boundary, particularly in the British sphere of influences which Johnson did from July 1, 1899, to December 1901.”

In the February 16, 1976, edition of the Voice of Uganda newspaper, it was reported that Amin ordered all Ugandans to buy that book and know the geographical facts of their country.

He also said he had an agreement signed by then British colonial secretary of state Herbert Asquith transferring some parts of Uganda to Sudan in 1914 and to Kenya in 1926.