Church Missionary Society prepares eight for Uganda voyage

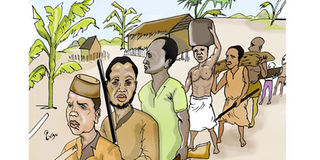

Journey. An illustration of the missionary’s caravan leaving Zanzibar for Uganda in 1876. ILLUSTRATIONS BY IVAN SENYONJO

What you need to know:

Arrival. Following Kabaka Muteesa’s invitation of missionaries in Buganda in the early 1870s, eight men bound for Uganda set sail from Liverpool, England, for the East African coast in April 1876. But the missionaries where not prepared for what they met, writes Henry Lubega.

Three years after the publication of Henry Stanley’s letter by the Daily Telegraph inviting missionaries to Uganda, Alexander Mackay, one of the outstanding figures in the group, reached the country.

The letter dated April 14, 1875, was published on November 15, 1875. On the day of its publication, according to Sophia Lyon Fahs’s Uganda’s White Man of Work, newspaper vendors were calling out “latest news from Stanley”.

The journey of the letter to London was a miracle in itself. The initial carrier of the letter from Kabaka Muteesa’s palace was killed on his way, but the letter was discovered in his jungle boot and it continued its journey to London.

Asking to be enlightened

A few days after his arrival in Buganda, Stanley was taken to meet Kabaka Muteesa.

He described the road to the palace as “a broad, well-built road leading to the top of a hill, where stood a high, dome shaped hut built of reed grass… Muteesa seemed like some great Caesar of Africa”.

But before Stanley’s arrival, Arab traders had made contact with the kingdom. As a result, they also introduced Islam in Buganda. Thus Stanley found Muteesa and his close chiefs subscribing to Islam.

At one time, Muteesa was forced to inquire about the White man’s God.

While at the palace were he had gathered his chiefs, officials and guards, Muteesa said: “When I became king, I delighted in shedding blood because I knew no better. I was only following the customs of my fathers.”

“But when an Arab trader came and taught me the Mohammedan religion, I gave up the example of my fathers. Now, God be thanked, a White man, Stamlee (Stanley), has come to Uganda with a book older than the Koran of Mohammed. Now I want you, my chiefs and soldiers, to tell me what we shall do. Shall we believe in Isa (Jesus) and Musa or in Mohammed?”

“I say that the White men are greatly superior to the Arabs, and of all that Stamlee has read from this book I see nothing too hard for me to believe. Now I ask you, shall we accept this book or Mohammed’s book as our guide?”

After a discussion between his chiefs Kauta and Kyambarango, Muteesa reached a verdict. There was a general consensus to go with Stanley’s book. That was when Muteesa asked for the letter inviting the White missionaries.

“Stamlee say to the White people when you write to them, that I am like a man sitting in darkness, or born blind, and that all I ask is that I may be taught how to see,” Muteesa said.

Sending the letter to London

According to Uganda’s White Man of Work, a young Frenchman who was with Stanley at the time wished to return to Europe.

Gladly taking the letter with him, he marched northward along the bank of River Nile. One day they were attacked by a band of savage tribesmen and the Frenchman was killed and his corpse was left lying unburied on the sand.

Later some English soldiers passing by discovered the body. Hidden in one of the boots was Stanley’s letter. The soldiers forwarded the letter to Egypt and later to England and it got published.

“King Muteesa of Uganda has been asking me about the White man’s God. Although I had not expected turning a missionary, for days I have been telling this Black king all the Bible stories I know. So enthusiastic has he become that already he has determined to observe the Christian Sabbath as well as the Mohammedan Sabbath, and all his great captains have consented to follow Muteesa’s example,” Stanley’s letter reads in part.

He went on to say that Muteesa had promised to give the willing missionaries all that they may need such as houses, land, cattle and ivory, among others.

Stanley explained that it was not a mere preacher that was wanted in Buganda, but a practical Christian who could teach people how to become Christians, cure their diseases, build dwellings and teach farming.

“Such, if he can be found, would become the saviour of Africa,” Stanley wrote.

He asked the British public not to worry of cost, saying Muteesa would “repay its cost tenfold with ivory, coffee, otter skins of a very fine quality, or even in cattle, for the wealth of this country in these products is immense”.

Reaction to the letter

Before Stanley’s letter was published, the Church Missionary Society (CMS) set up a committee called the secretaries of the Church Missionary Society.

Their responsibility was to collect money from churches and well-wishers to fund the task of sending out missionaries to different parts of the world.

After reading Stanley’s letter, the secretaries gathered in an office in Salisbury Square in London to plan what to do.

They, however, had some reservations about the African king’s personality. “Is there anything we can do for King Muteesa? If he is truly longing to be taught about God, will it not be a crime to refuse to send someone to tell him, even if he is not sincere?” they observed.

At the end of the day, their main concern was funds. Three days later, the secretary to the Church Missionary Society, Ed Hutchinson, received a letter from a donor.

“Often have I thought of the people in the interior of Africa in the region of Uganda, and I have longed and prayed for the time to come when the Lord would open the door so that heralds of the gospel might enter the country,” the giver’s letter reads in part.

“The appeal seems to show that the time has come for the soldiers of the cross to make an advance into that region. If the committee of the Church Missionary Society are prepared at once and with energy to start a mission to Victoria Lake, I shall gladly give you £5,000 with which to begin. I desire to be known in this matter as An Unprofitable Servant.”

CMS received another donation of the same amount from another unidentified donor. Its total budget for the Uganda mission was £24,000.

As the secretaries sent out donation request letters, they also sent out letters to newspapers asking for people willing to go to Uganda.

Among the responders was a retired officer of the British navy, Lt Shergold Smith, an Irish architect, O’Neill, a physician from Edinburgh, Dr John Smith, an artisan, William Robertson, an engineer, Clark, a carpenter, James Robertson and Rev CT Wilson.

The secretaries wanted seven people, but one of them, Robertson, was turned down on health and old age grounds. Robertson, however, insisted on going. He was ready to pay for himself having sold his house for the cause.

CMS allowed him. But there was a late expression of interest from a young Scottish man who was in Germany. The man, Alexander Mackay, was the youngest in the team. At the time he was drawing plans for large engines in a German machine factory.

Before Stanley’s letter, Mackay had wanted to go to Madagascar as an engineering missionary “to teach the natives to build roads, bridges, railways, to work mines and to learn to use various kinds of machinery, and so help them to become more useful Christians,” according to Alexina Mackay Harrison in her book Pioneer Missionary of the Church Missionary Society to Uganda. Alexina was Alexander Mackay’s sister.

The journey

In April 1876 in the committee room of the Church Missionary House, the eight men bound for Uganda said their goodbyes.

Each had some parting words and Mackay being the youngest was the last to speak.

“There is one thing which my brethren have not said, and which I want to say. I want to remind the committee that within six months they will probably hear that one of us is dead. When the news comes, do not be cast down, but send someone else immediately to take the vacant place,” Mackay said.

They set sail from Liverpool, England, for the East African coast. At Zanzibar, they bought more supplies from the Indian and coastal traders who stocked supplies used by explorers coming to the interior. The traders also supplied labour in terms of porters.

The missionaries broke into four caravans, each setting off at different dates. Mackay’s was the last to leave Zanzibar.

But, as he had predicted in his parting remarks, before the departure of the last two caravans the angel of death visited the team. James Robertson, the carpenter who sold his house to join the party, died four months after setting off from Liverpool.

Mackay’s caravan was quarter a mile long and they would walk half a day, starting before sunrise to noon.

Once they reached their resting place tents would be pitched and goods piled under a tree or in a tent. After that, the head of the caravan would go to Mackay’s tent and call out, “Posho, Bwana” (rations, master). They were given meters of cloth which they exchanged for food with the locals.

After covering 300 miles, Mackay fell ill and had to be taken back to Zanzibar. While there, a letter from London came asking him not to travel until mid-year when the rainy season in the interior has stopped. He set off for the journey to Uganda in August 1877, reaching Buganda in November 1878.

When he finally made the journey, Mackay wrote: “I have slept in all sorts of places; a cow-stable, a sheep-cote, a straw hut not much larger than a dog-kennel, a hen-house, and often in no house at all. So anything suits me, provided I get a spot tolerably clear of ants and mosquitoes. Of all the plagues, none could have been worse than that of the black ants.”