How 1900 Buganda Agreement changed land ownership

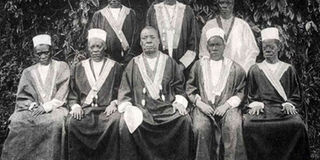

Kingdom officials. Regent Stanislas Mugwanya (centre) with other Buganda chiefs in the 1890s, during the reign of Kabaka Daudi Chwa II. Regents and chiefs were beneficiaries of land distribution following the 1900 Buganda Agreement that rewarded them for their collaboration with the British. FILE PHOTO

What you need to know:

- 120 years ago. Following the enactment of the agreement, land in Buganda was divided into Mailo and crown land. Mailo land belonged to Buganda government and its officials, while crown land belonged to the protectorate government.

- As a result of Article 15, natives who were not from the royal family, kingdom officials or privileged individuals were rendered landless, writes Henry Lubega.

Tuesday, March 10, will mark exactly 120 years since Buganda Kingdom under Kabaka (king) Daudi Chwa jumped into bed with the British.

The signing of the agreement not only took away the entitlements of the kingdom, but paved way for patronage and plundering of other parts of Uganda.

The agreement entrenched British rule in Buganda and also gave the Baganda a chance to extend their influence to other parts of the country. Areas that were not under kingdoms were taken over by Buganda neo-colonial agents like Semei Kakungulu.

The 1900 signing was achieved after years of negotiations led by Bishop Alfred Tucker. Little wonder the Anglican Church under the Church Missionary Society took the lion’s share in the new administration after the signing of the agreement.

The agreement had three sections: power sharing, system of government finance and land. But it came with difficulties as Kabaka Chwa was only a minor who did not have a hand in the negotiations.

As a result, the three regents – Sir Apollo Kaggwa, Zakaria Kisingiri and Stanislas Mugwanya – signed on behalf of Chwa, while Sir Harry Johnson signed on behalf of King Edward VII.

Under Article 6 of the agreement, the Kabakaship surrendered its authority and power to the colonialists.

“So long as the Kabaka, chiefs and the people of Uganda shall conform to the laws and regulations instituted for their organisation and administration of the said kingdom of Uganda, Her Majesty’s government agrees to recognise the Kabaka as the native ruler of the province of Buganda under Her Majesty’s protection and over-rule,” Article 6 of the agreement reads in part.

Daudi Chwa, who was a minor at the signing of the agreement, said when he came of age that the British control had watered down his authority.

“My present position is so precocious that I am no longer the direct ruler of my people. I am being considered by my subjects as merely one of the British paid servants. This is solely due to the fact that I pose no real power over my people, even the smallest chieftainship,” Chwa said according to Baganda and British overrule 1900-1995 by Low and Pratt.

“Any order given, whether by my local chief or by the Lukiiko itself, is always looked upon with contempt unless and until it’s confirmed by the provincial district commissioner.”

The oath of office Chwa took when he came of age showed how much Buganda had been subjugated.

The Uganda Herald newspaper of August 14, 1914, reproduced the oath: “I Daudi Chwa, do swear I will well and truly serve our sovereign Lord King George V in the office of Kabaka of Buganda and will do right to all manner of people after the law and usage of the Protectorate of Uganda without fear or favour, affection of good will. So help me God.”

The British not only wanted to be the lords of the kingdom and its people, but also have a say in who becomes the next Kabaka.

“On the death of a Kabaka, his successor shall be elected by a majority of votes in the Lukiiko, or native council. The name of the person chosen by the native council must be submitted to Her Majesty’s Government for approval, and no person shall be recognised as Kabaka of Uganda whose election has not received the approval of Her Majesty’s Government,” Article 6 went on to say.

Prior to the signing of the agreement, the Kabaka of Buganda chose his officials without consultation.

But Article 10 of the agreement reserved the approval of the top three officials to Her Majesty’s representative.

“To assist the Kabaka of Uganda in the government of his people, he shall be allowed to appoint three native officers of state, with the sanction and approval of Her Majesty’s representative in Uganda (without whose sanction such appointments shall not be valid)-a prime minister, otherwise known as Katikkiro; a chief justice; and a treasurer or controller of the Kabaka’s revenues,” it reads in part.

An illustration of Kabaka Daudi Chwa II. ILLUSTRATION BY IVAN SENYONJO

Before the signing of the agreement, all land in Buganda belonged to the Kabaka, hence the title of Sabataka.

However, with the signing of the 1900 agreement, the Kabaka, members of his family and his chiefs were allotted chunks of land in their capacity as office holders and also individual capacity.

The land issue was dealt with in Article 15 which estimated the total acreage of land in Buganda at 19,600 square miles.

But the agreement also stated that should a survey be carried out and it was discovered that Buganda had less than 19,600 square miles, “then that portion of the country which is to be vested in Her Majesty’s government shall be reduced in extent by the deficiency found to exist in the estimated area.”

Following the enactment of the agreement, land in Buganda was divided into Mailo and crown land. Mailo land belonged to Buganda government and its officials, while crown land belonged to the protectorate government.

The Mailo land was further divided to members of the royal family, kingdom officials and some individuals. Other beneficiaries were the religious institutions.

By the signing of the agreement, the figures in the acreage allotted were in estimates. After the survey, the parties to the agreement were to sit and conclude on what the agreement had decided after the allotment. This culminated in the 1913 Buganda Allotment Agreement.

As a result of Article 15, the natives who did not fall in the categories of people who were allocated land were rendered landless. They became squatters.

Also introduced under the agreement was the taxation system which was to fund the new administrative structure.

Hut and gun taxes were introduced. Each hut in a homestead was taxed four Rupees per year while any individual who owned a gun paid three Rupees for the gun per year as per Article 12 of the agreement.

For the first time, the Kabaka and his chiefs were to earn an annual salary from Her Majesty’s government. Article 6 dealt with the payments from the Kabaka to the Sazza chief.

This was a new development in the Ganda administration. The three regents were entitled to £400 per year until the young king came of age.

The Kabaka was to get £400 per year, Sazza chiefs £200, the three state officials -- prime minister, chief justice and treasurer -- £300 each, while the Namasole (mother of Chwa) was to get £50. This was an annual fee collected from the hut and gun tax.

About Buganda deal

The land issue was dealt with in Article 15 which estimated the total acreage of land in Buganda at 19,600 square miles.

But agreement also stated that should a survey be carried out and it was discovered that Buganda had less than 19,600 square miles, “then that portion of the country which is to be vested in Her Majesty’s government shall be reduced in extent by the deficiency found to exist in the estimated area.”

Following the enactment of the agreement, land in Buganda was divided into Mailo and crown land.