How Buganda became a constitutional monarchy

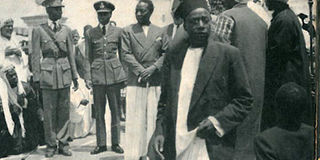

Hero’s welcome. Former Kabaka of Buganda Edward Muteesa (C) is welcomed by religious leaders at Kibuli mosque in Kampala following his return from exile in 1955. PHOTOS COURTESY OF FAUSTIN MUGABE

What you need to know:

- Agreement. Under the agreement signed on October 18, 1955, the Kabaka as well as his prime minister, would be elected by the members of the Buganda legislative council, Faustin Mugabe writes.

As it is today, Buganda Kingdom is supposed to be a constitutional monarchy. The Lukiiko, Buganda’s legislative council, is supposed to have the authority to oversee whatever business is conducted on behalf of the kingdom, unlike before when all power was vested in the Kabaka.

And this goes back to October 18, 1955, when Buganda ceased to be an absolute monarchy. The hitherto powerful kingdom in central Uganda lost some of its powers after the signing of the 1955 Buganda Agreement, also known as the Namirembe Agreement or Buganda Constitution of 1955.

Since its establishment nearly 1,000 years ago by its first king Kintu, Buganda Kingdom had always been an absolute monarchy. All power was centred on the Kabaka. Therefore, the king would do whatever he wanted as and when he wished.

But this was changed when Kabaka Edward Muteesa II decided to fight the British, Uganda’s colonial masters. The collision did not only leave Buganda bleeding, but it also led to Muteesa’s deportation to the United Kingdom in November 1953 by the British government.

When the Buganda Agreement of 1955 was signed, as a kingdom, Buganda lost the political power it had.

The 1955 agreement

On October 18, 1955, a day after Muteesa returned from exile, he appended his signature on the Buganda Agreement on behalf of the kingdom.

Then Governor of Uganda Andrew Cohen, who commanded Kabaka’s arrest and deportation in 1953, signed the agreement on behalf of the Queen of England.

The agreement set out how Buganda Kingdom would be governed. Article(1) stated: “The kingdom of Buganda under the Kabaka’s government shall continue as heretofore to be an integral part of the Protectorate of Uganda.”

The constitution further stipulated that the Kabaka, as well as the prime minister, Katikkiro, would be elected by members of the Buganda legislative council. Until then, the Kabaka had often chosen the Katikkiro.

Although Buganda went to court and sued the Queen of England for the deportation of Kabaka Muteesa and won the case, diplomatically England won.

It forced the Kabaka to sign a new agreement in which Buganda became a constitutional monarchy, and worst of all, the previously hereditary Kabakaship became an elective office.

Kabaka Muteesa had to take an oath to be loyal to the Queen of England and all her heirs and successors.

While Muteesa had opposed the Kabaka being a subordinate to the Queen of England and had also objected to the 1900 Agreement which placed Buganda Kingdom under the Kingdom of England, the Buganda Agreement of 1955 was only a replica of the 1900 Agreement which Muteesa had to sign before assuming office.

Provision (2) under chapter 5 reads: “His Highness Muteesa II, before assuming the functions of his office under this present constitution, shall enter into the solemn undertaking with Her Majesty and with the Lukiiko and people of Buganda in the presence of the governor and representatives of the Lukiiko and, so long as he observes the terms and the said solemn undertaking, he shall be entitled to perform the functions conferred upon the Kabaka by this constitution.”

Elective office

The office of the Kabaka became an elective post. If we were to uphold the Buganda Agreement of 1955, the current kabaka would have been elected by the Buganda Lukiiko.

But Kabaka Ronald Mutebi II was instead enthroned to Buganda’s Namulondo in 1993 as was traditionally done before the 1955 Agreement.

Article 3 of the 1955 Buganda constitution reads: “The Kabaka shall succeed as heretofore to the throne of Buganda by descent and election of the great Lukiiko.

The name of the person chosen by the great Lukiiko must be submitted to Her Majesty’s government for approval, and no person shall be recognised as Kabaka of Buganda whose election has not received the approval of Her Majesty’s government.”

About the title of the Kabaka, the constitution says: “The Kabaka of Buganda, who is the ruler of Buganda, shall be styled ‘His Highness the Kabaka’ and shall be elected as hitherto, by the majority of votes in the Lukiiko.”

Muteesa (C) and his prime minister (R) are greeted by his subjects following his return from exile in 1955.

But not everyone was eligible to stand as Kabaka; only members of Kabaka Daudi Chwa II’s family.

“The range of selection must be limited to the royal family of Buganda, that is to say, the descendants of Kabaka Daudi Chwa II and the name of the prince chosen by the Lukiiko must be submitted to Her Majesty’s government for approval and no prince shall be recognised as Kabaka of Buganda whose election has not received the approval of Her Majesty’s government,” The constitution clarifies.

The constitution goes on to emphasise that before any prince is recognised by Her Majesty’s government as Kabaka, “he shall enter into a solemn undertaking in accordance with the provisions of the constitution set out in the First Schedule to this agreement; and so long as he observes the terms of the said solemn undertaking, Her Majesty’s government agrees to recognise him as ruler of Buganda.”

The oath

Perhaps the bitter pill for Muteesa to swallow was the solemn undertaking.

“I do hereby undertake that I will be loyal to Her Majesty Queen Elisabeth II, whose protection Buganda enjoys, her heirs and successor and will well and truly govern Buganda according to law and will abide by the terms of the agreements made with Her Majesty and the Constitution of Buganda,” he said as he held the Bible during the swearing-in ceremony.

He added: “I will uphold the peace, order and good government of the Uganda Protectorate and will do right to all manner of people in accordance with the said agreements, the constitution of Buganda, the laws and customs of Buganda and laws of the Uganda Protectorate without fear of favour, affection or ill-will.”

1955 Buganda constitution

Article 3 of the 1955 Buganda constitution reads: “The Kabaka shall succeed as heretofore to the throne of Buganda by descent and election of the great Lukiiko. The name of the person chosen by the great Lukiiko must be submitted to Her Majesty’s government for approval, and no person shall be recognised as Kabaka of Buganda whose election has not received the approval of Her Majesty’s government.”

Reaction

By Apolo Kaggwa

Dear Editor,

I beg to dispute Faustin Mugabe’s account that Ssekabaka Edward Muteesa was “abducted” and ‘bundled” to his exile from Entebbe to London as contained in the story ‘Muteesa is blindfolded, bundled into plane and flown to exile, in Sunday Monitor of October 20.

We have an eyewitness account of the events that day from Paulo Kavuma, then Katikkiro (prime minister), with whom the Kabaka had been summoned to Entebbe by then Governor of Uganda, Sir Andrew Cohen.

His account of what happened at Entebbe that day is carefully recalled in his book, The Uganda Crisis.

Actually, the order to exile the Kabaka did not come directly from Her Majesty the Queen, but rather it was a decision made by the governor of Uganda on behalf of Her Majesty’s government in London - which Cohen would later regret.

Katikkiro Paulo Kavuma writes that Ssekabaka Muteesa was armed with his service pistol as a colonel of the Grenadier Guards and was prepared to use it if necessary.

That was when the Katikkiro removed his coat, unbuttoned his shirt, exposing his bare chest to the Ssekabaka Muteesa, and pleaded with him not to take that step, but rather shoot him instead.

He writes that had Muteesa fired his pistol at the British colonial officers, matters would have turned grim for Buganda.

In fact, according to Kavuma, the British soldiers who had taken to shoving Muteesa into the plane, were immediately cautioned by him, saying he should be allowed to walk freely into the plane. They immediately obeyed the Katikkiro.

Had Muteesa been “blindfolded” while entering that plane, the Katikkiro would have mentioned that detail in his book, but he never did.

Katikkiro Kavuma continues in his account by pointing out that as soon as the military plane carrying Muteesa had taken off, Cohen turned and, facing the Katikkiro, ordered him to “choose” a new Kabaka.

His response was characteristically immediate and quite stern.

“It is impossible to do so,” he said, because according to the customs of the Baganda, accession only happens at the passing of the incumbent and never whilst he is alive.

We now know that two years later, Sir Andrew Cohen lost that war because “he had no authority,” according to the court ruling, to exile the Ssekabaka Muteesa.

That led to Muteesa’s return to Buganda, Cohen being recalled and Sir Frederick Crawford’s appointment as the new governor.