Uganda resolves to deport 200 Britons over anti-African fete

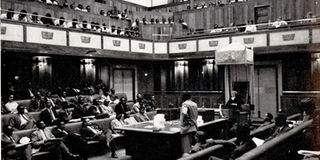

Parliament in session in the early 1960s. The anti-African merrymaking rattled MPs who called for the organisers’ imprisonment. PHOTOS/ FILE

What you need to know:

- To some parliamentarians, deportation was a very lenient punishment. MP Medadi Omani demanded an immediate drafting of a detention order for all the attendees of up to 100 years, saying hell was where they should go, writes Henry Lubega.

Just a year after handing its former colony independence, Britain and Uganda found themselves at the brink of severing diplomatic relations. This was because of a party at Tank Hill, Kampala.

In late 1963, five British men of between 23 and 32 years, calling themselves the League of Ex-Empire Loyalists, met at Kampala Sports Club and planned a house party in December 1963. The party was by invite only.

“We the League of Ex-Empire Loyalists do request and require your presence, at A Bottle Colonial Sundown on Wednesday, December 11, commencing at 9pm to celebrate the end of the White man’s burden,” the invitation card read. About 200 guests turned up for the transnight party.

But three weeks later, what happened at that party threatened the Uganda-Britain relations. This was after rumours made the rounds in Kampala that the partygoers had dressed dogs in Ugandan and Kenyan flags, and that effigies of African heads of state were made and subjected to all sorts of humiliation.

Because the party was for Whites only, it was taken as a racial abuse.

Writing in The Second British Empire: In the Crucible of the Twentieth Empire, Timothy Parson says, “The Tank Hill party provoked a collective recognition of the emotional wounds created by racial injustice at the heart of colonial governance and sociality.”

Unknown to the host, one of his houseboys was a UPC Youth League informer.

“The youth wing network had been established among the servants in European households. The youth were alerted. Raiti Omongin [UPC Youth League leader] dug out every detail, and provided full information to the government to act,” writes Kirunda Kivejinja in The Crisis of Confidence.

The houseboy, only identified as Musso, later repeated to the police what he had told the Youth League.

“A group of Europeans gathered and enjoyed their booze. During these celebrations, they got a cloth in the colours of the Kenya flag and clad it on their dog,” Musso told police.

At the time, Uganda was host to at least 3,000 British nationals, many of whom were in the civil service. Chief organiser and host of the party was Tony Lawrence, a British national serving in the Uganda civil service.

Other organisers included Simon Saben, Michael Rogers, John Steed and Colin Sibley, all members of Kampala Sports Club.

Among the attendees was Christine Partington Dove, then country manager Save the Children Fund, who turned up dressed in a Busuti.

Police report

The Inspector General of Police at the time was Michael Macoun, a British national. He headed the investigations.

The other two involved in the investigations were police superintendent Leonard Taylor and Gerald Murphy, all British nationals. Taylor, like the party organisers, was a member of Kampala Sports Club.

It was discovered during investigations that besides the 200 White guests, there were seven Ugandans present at the house. They included two houseboys, two club stewards and three night watchmen. Musso was among them.

At midnight as Kenya was being declared independent, the party-goers sang God Save the Queen, Britain’s national anthem. The party had been organised to coincide with Kenya’s independence.

Although government ordered for investigations into the matter, inquiries proved difficult as police was heavily staffed by the British. Hence both the British High Commission kept a close tab on the investigations.

IGP Macoun and officer Murphy covertly reported directly to High Commissioner Hunt, who reported back to London on the progress of the investigations. Murphy is said to have taken copies of the CID files to the British High commissioner.

The two officers officially reported to the permanent secretary Ministry of Internal Affairs, Michael Davis, also a British national. Davis was another source of information for the British government on what was happening in Uganda.

Residencies of some of the party organisers were visited as part of the investigations and objects said to have been used in the party were presented to prime minister Milton Obote as exhibit.

They included a piece of wood-work intended to represent the head of an African, a cleft stick, lyric sheets and song recordings. Others were the busuti worn by Ms Dove and copies of the invitation.

Government’s reaction

Obote convened a Cabinet meeting during which he presented the police report. According to Cabinet minutes of December 17, 1963, minute 669, Obote believed the party was meant to show disrespect for Africa and its leaders.

“The evidence clearly showed that the organisation had a hostile and contemptuous attitude towards Africans and African governments,” he said.

On the strength of the evidence presented, Cabinet resolved to have all those whose names were on the invited list to be deported.

“All civil servants who attended the party, and those whose wives attended although they themselves did not, should also be deported,” Cabinet resolved.

Some of those affected by the Cabinet resolution included Barbara Saben, the first female mayor of Kampala. Her son Simon Saben was one of the organisers and was to be deported. She went to the prime minister to plead for her son, but in vain.

“The theme of the party having been clearly anti-African, it is most insulting for the deported persons to attempt to appeal to the sentiments of the people by using the name of the president as if the president is not an African,” Obote said.

After presenting the police report to Cabinet, Obote presented the same to the National Assembly. Watching from the gallery were the British high commissioner and IGP.

In the National Assembly, Obote recited parts of some songs alleged to have been sang at the party. “The sewerage works will soon break down. The place will stink like mad. That is not mbaya (bad). That is not a bad thing for the African. It is what we have always had. We are bound to make a few mistakes. We have not got the brains and also it is undignified for men to clear out drains,” Obote said, adding that: “I think I have shown you enough to prove that this was not an ordinary party and this was not a mere joke.”

His speech caused an uproar with parliamentarians calling for harsher punishment. First to react was Francis Mugeni, who said, “The partygoers regarded an African an animal with four legs. This is the sort of thing we cannot stomach.”

To some parliamentarians, deportation was a very lenient punishment. MP Medadi Omani demanded an immediate drafting of a detention order for all the attendees of up to 100 years. “Hell is where they should go,” he said.

Demands for a severe punishment were not only coming from government, but also from the Opposition. Vincent Rwamwaro declared that “it is useless to regard any longer any White man who is here as a friend.”

In his book Wrong Place, Right Time: Policing the End of Empire, IGP Macoun said: “The situation was on razors edge. I feared arson, indiscriminate assaults and looting.”

Severing diplomatic ties

Seeing the response of MPs, the following Cabinet meeting resolved to cut off diplomatic ties with Britain.

In a memo from Hunt to Walsh Atkins, then Assistant Secretary of State for Commonwealth, the high commissioner quotes Health minister Emmanuel Lumu talking of the possibility of cutting off diplomatic ties as “it had powerful support”.

But Obote and high commissioner Hunt managed to neutralise the situation by the end of December 1963. Each assured the other of their commitment to the normalisation of relations.

“We have no quarrel with either the British government or the British High Commission in Uganda over this matter. Our relations with the British government, the British community in Uganda and the British High Commission remain cordial,” Obote said.

Savile Garner, then Permanent Undersecretary of State for Commonwealth Relations, responded by calling the whole saga “a serious error in judgment that can get back into the obscurity that history may accord it, because what is important is that the future of Uganda and of this country should run smoothly.”