Who will heal Uganda’s sick health sector?

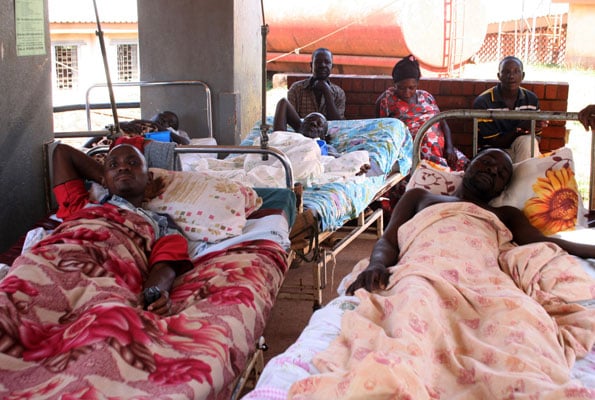

Patients and their attendants camped outside the endocrinology unit at Mulago Hospital in the past. PHOTO/FILE

When his teenage wife went into labour, John Emegu wedged her on a bicycle between himself and his grandmother and pedalled furiously for 11 miles. But on reaching the nearest hospital, his relief quickly turned to despair.

Though healthcare is meant to be free in Uganda, nurses told him to buy a Shs20,000 maternity kit including rubber cloves, saline solution, surgical needle and a plastic ‘delivery’ sheet, which were all out of stock in the hospital. By the time he had done so—and paid another Shs10, 000 to convince an intern doctor to attend to his wife—12 hours had passed. “I don’t know what is happening,” said Emegu, 22, as he waited for news at Soroti regional referral hospital. “I am getting desperate.” His wife and newborn baby survived—unlike his first child who died in the same hospital the year before.

The Emegus’ traumatic experience is not unusual in a country, where the healthcare system is in crisis despite the billions of shillings of mostly donor money flowing in every year. Visits to a dozen health centres across the country revealed a chronic shortage of beds, drugs and medical personnel, confirming a recent verdict by the Anti-Corruption Coalition of Uganda that “service delivery and general care is almost not there”.

The government admits that the situation is dire. “Lack of adequate resources is still limiting hospitals to provide the services expected. In many instances, basic emergency infrastructure, supplies and specilised equipment are inadequate,” reads the latest annual health sector performance report. The dire situation has meant that senior government officials and wealthy Ugandans have long used private hospitals or flown outside the country for treatment, as was the case with some of President Museveni’s daughters, who delivered their children in Germany.

Members of Parliament are registered with private health insurance companies of their choice, paid for by taxpayers. But now even ordinary Ugandans, the intended beneficiaries of the free healthcare system, are increasingly seeking private healthcare. “I don’t see any reason of wasting time; you go to the government hospital yet there are no drugs,” said Joseph Kusemerwa, a resident of Kicucu village, Kabarole District in western Uganda.

So why is it dysfuntional?

Such attitudes are stirring public debate on why the free healthcare system is so dysfunctional. While it is expensive to run, money does not seem to be in short supply. Donors gave more money towards health than any sector of government, amounting to Shs321 billion in 2009/2010.

The government added a further Shs465 billion and this year Shs1.3 trillion went to health. In total, health spending accounts for 9.6 per cent of the budget, significantly higher than the sub-Saharan average of 8 per cent. Local healthcare monitoring groups and government officials say Uganda’s heavy reliance on outside funding is one of the main problems, with a lack of overlap between the government’s priorities and those of donors.

The focus of HIV prevention and treatment is one example. While 1 million Ugandans are estimated to be HIV positive—3.3 per cent of the population—some Shs549 billion went to Aids campaigns in the financial 200/2010, more than half of total healthcare budget. Most of the money came from the US’s Pepfar (President’s Emergency Plan for Aids Relief) and USAID.

‘Unreliable donor funding

Local players in the sector say the unpredictability of the donor funding makes it difficult to plan and when it comes, there is lots of overhead expenditure and what is spent on actual projects is actually less. “The money, which is off budget, has had issues of accountability, which has resulted in delayed release of other funds. Some such as Gavi have been withheld. If we had an organised system of receiving even off budget funds, we should not be seeing such problems,” said the Health Ministry Permanent Secretary, Mr Asuman Lukwago.

The effect of the heavy HIV focus is clearly visible; even in rural areas the voluntary counselling and testing centres are usually well-equipped compared to the general health units. In Kabarole District in Western Uganda, Rose Kayesu, 24, was battling malaria at home. The nearest health centre only had one type of malarial drug, and she was allergic to it. Enock Kibite, her husband, said he sometimes spends more than half of his Shs75,000 monthly earning from carpentry on malaria drugs alone.

According to the Director General of Health Services, Dr Ruth Achieng, the bulk of donor support to the health sector (41 per cent) is off budget and a significant proportion (21 per cent) of government expenditure on health mainly goes to emoluments. Sector players also point to poor coordination among health system players and this has led to fragmentation of services. “Actors have immense interest in M & E (data), at the expense of investment in service delivery. Many actors are measuring the same indices,” said Dr Achieng.

District health directors, many of whom did not want to be named for fear of reprisal, said it was “unacceptable” to run out of drugs, but also unavoidable. “There’s no money,” a director said. Government’s 2009/2010 health sector report shows that only 35 per cent of health centres do not run out of essential drugs. As of August, reports on the ministry website indicate that stocks available at both the National Medical Stores and Joint Medical Stores are generally below recommended minimum central stock level and health centres also registered low stock levels of essential drugs.

The corruption drawbacks

But corruption is a major problem hampering healthcare delivery. The Auditor General’s 2009 report shows that Shs310m meant for drugs went missing that year. “The end users did not also have knowledge of these (missing money, deliveries either). The missing drugs included ARVs, coartem, condoms and oral rehydration salts,” the AG report said.

In November 2010, the National Drug Authority said more than 100 ghost health centres created by corrupt officials had been receiving medical supplies and equipment. By contrast, many genuine health centres lack even basic equipment. So in places like Awcha, Gulu District, the theatre serves as a ward. At Kiyombya Health Centre, Southern Uganda, mothers in the maternity section are expected to pay for parafine for lamps.

Large sums of money are simply stolen. In 2005, nearly Shs150b from the Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunisation (Gavi) and the Global Fund to fight Aids, tuberculosis and malaria was unaccounted for. “The healthcare system is very sick but the one who is supposed to heal it is very corrupt,” said the Anti-Corruption Coalition Uganda in its report.

Brain drain effects

There is also a major shortage of medical professionals. Kitgum Hospital in northern Uganda had five doctors in the 1980s. Today, there is one. Arua Hospital needs 38 doctors but has 11; Kabale has five instead of 35.

Data from the Health Ministry indicates the country has only 37,368 health workers. Of these, 8,978 are nurses, 4,535 are midwives, and only 1,118 (3 per cent) are doctors. Data also indicates that nursing assistants still form a big number of the health workers--6,371 (17 per cent). “If we don’t handle this problem now, in the next 10 years, Uganda will have no clinicians or physicians,” former Director General for Health Services, Dr Sam Zaramba, warned at a health conference last year.

The World Health Organisation says Uganda’s doctor-to-patients ratio of 1:25,000 is low even by African standards. Uganda graduates more than 200 doctors every year but most migrate to neighbouring countries such as Rwanda where pay and working conditions are better. However, even the few medical workers employed in Uganda’s health sector often abscond from duty. Government investigation show that 40 per cent of doctors and 50 per cent of nurses receive salary but are absent from duty.

In cases where money has been spent on appropriate inputs such as medical supplies, in many cases the staff to dispense the supplies are absent or not recruited. “You find that the same doctors supposed to be working for the government are also working for donor funded projects yet our numbers are already few. This worker is over stretched and they cannot be efficient any more. And the reasons I have heard cited for leaving government facilities is little pay,” said Dr Lukwago

Dr Achieng puts the problem candidly as, “ethical erosion.” Some Shs2.6 trillion is needed to rehabilitate hospitals across the country, the ministry says. For clinicians like Mr Richard Kyeyune, and the patients who visit the dilapidated health centre he runs in Masaka District, that money can’t come soon enough. “When it rains, we send patients away because we are scared the roof will fall on them,” he said.

When skewed priorities hurt heath care delivery

When the money does get through spending priorities often seem skewed. In 2009, Shs439million meant for medicine was diverted to foreign travel. Parliament last months rejected the Health Ministry’s budget after they discovered that the ministry officials had diverted more than Shs2 billion meant for maternal health to seminars and workshops on HIV/Aids, among others.

A scenario given by Uganda Medical Workers’ Union show that the ministry of health owns expensive recent model 4x4 vehicles, totaling 2,935, yet hospitals in smaller towns often lack a single functional ambulance.

In Soroti, there is an ambulance – but no fuel. After Jocy Asio’s father paid Shs30,000 for petrol, the 19-year-old suffering from post-natal bleeding was rushed to the hospital only to be told there was no blood. At health centres like Kinoni, Mbarara, a double-cabin truck is used as an ambulance. The medical workers’ union point in a document that the ministry official vehicles can provide three well- equipped ambulances per sub-county and the Shs28 billion spent on fuel can build and equip five open heart surgery units.

At Mulago National Referral Hospital, it is not uncommon to see patients sleep in the corridor in the night due to overwhelming number, mothers in labour being shuffled, due to inadequate number of beds and patients often diagonise but asked to buy medicines from private pharmacies or clinics.“We put four of them (children) on the bed and some sleep on the floor,” said a health worker in Kyenjojo, western Uganda, explaining how he deals with overcrowding.

Meanwhile, programmes to tackle malaria, which is the number one killer disease in Uganda, as well as diarrhea, respiratory diseases, maternal and infant mortality, are chronically underfunded. “HIV/Aids and direct project funding affects funding for other sectors. We are insisting that the money is channeled into the system other than specific project funding,” said Dr Achieng during the health science week conference. “There is a need to look at the system as a whole, from human resource to infrastructure.”

State of hospitals

GULU HOSPITAL: The referral hospital is all but a dilapidated structure that has been condemned for human use, though plans are underway for a new modern hospital. Also, some sections have been refurbished. The maternity ward, children’s ward and medical ward have given some hope to visiting patients—if only service delivery was equalled.

Beds. The hospital is supposed to accommodate 250 inpatients but it overflows with more than 367.

Staffing. Specialist care remains a hurdle. Instead of having 40 doctors, there are only four doctors, of which two are retiring next year after reaching the retirement age and there is no replacement yet. According to the director of the hospital, Dr Athoney Onyach, a doctor on a daily basis is supposed to attend to only 30 patients but each is attending to up 100 patients.

Drugs. Supply has improved unlike in the past where patients referred to buy medicines from clinics and many skipped treatment due to biting poverty. Missing specialists. Ear, Nose and Throat doctor since 2005 when the structure was built (equipment are idle), pathologists left in 2006, gynecologist left two month ago.

-Cissy Makumbi

BUNDIBUGYO HOSPITAL: The hospital administrator, Mr Ronald Mutegeki, says the hospital is in a sorry state and needs to be overhauled. He said the sewer system broke down several years ago and the hospital is still using old equipment, for instance, fire extinguishers which were installed in 1969 when the hospital opened have never been replaced. The hospital uses sand for firefighting.

Staffing. The hospital lacks a dispenser, radiographer, staff accommodation, dressing equipment, an anesthetist and a specialist to work on an ultra sound scan. Equipment. The hospital also lacks autoclaves, refrigerators, sterilisers and an EMO machine (used when anaesthising patients).

Drugs. The stores assistant, Mr Erasto Kamadi, says the hospital has been running without switchers, flagyl, ciprofloxacine for six months and ORS for two years. The hospital also lacks gloves and patients are supposed to improvise before they are worked on.

-Joseph Mugisa

SOROTI HOSPITAL: An emergency operation had to wait for a couple of minutes. Reason? Load-shedding, and a standby generator for the hospital did not have fuel to run it. “It is a big challenge for us here, especially when we have an emergency to work on. Funds allocated for running the generator are not sufficient,” a doctor, who declined to disclose his identity for fear of reprisal, said.

Patients. The regional referral hospital also caters for Amuria, Bukedea, Kaberamaido, Katakwi, Kumi and part of Karamoja region. But authorities say it has not been able deliver to expectations due to numerous challenges ranging from inadequate staff to lacking to sufficient drugs.

Shortages. Dr Joseph Epodoi, a senior surgeon, said the hospital has a capacity of about 250 beds, which the unit has since outlived. He said the hospital is experiencing a high demand for blood due to increasing cases of malaria among children. The hospital currently depends on the Mbale-based blood bank.

Graft. A probe by the Health Services Delivery and Monitoring Unit in 2010 revealed massive graft, including theft under unclear circumstances of a computer containing vital information on the implementation of HIV/Aids programme at the hospital. It is alleged that last year, drugs worth Shs50m was stolen and about Shs7m meant for the repair of the hospital generator has since not been accounted for.

-Richard Otim