How Opolot reclaimed her life after abusive relationship

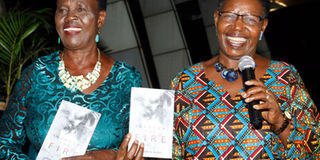

Author’s smile. Margaret M Opolot (left) displays a copy of her book together with former Ethics minister Miria Matembe during the book launch in Kampala recently. Photo by Bamuturaki Musinguzi

What you need to know:

Personal account: In a 160-page autobiography, Margaret M. Opolot captures her own sad experience of domestic violence in which she gives a harrowing and graphic account of the pain inflicted upon her by her ‘barbaric’ husband, writes Bamuturaki Musinguzi.

Unlike other women who die in silence when it comes to domestic violence, Margaret M. Opolot, has captured her own sad experience of the vice in an autobiography, Through The Fire, which she launched in Kampala recently.

In the 160-page book that is available in bookshops in Kampala at Shs25,000, Opolot gives a harrowing and graphic account of the battering inflicted upon her by her “barbaric and abusive husband” and father of her two children.

How it started

It all started when Opolot returned home in Soroti District in eastern Uganda from Kenya where she had been working for several organisations. Opolot, being the breadwinner for the family, her mother decided to consult a famous witchdoctor “to wade off people with ill motives” that could hurt the most successful girl in their village.

They consulted a popular witchdoctor named Mandwa, who allegedly conducted rituals for Opolot to keep off the evil-minded village mates.

One thing led to the other and Mandwa proposed to marry Opolot, and she accepted – a decision she finds difficult to explain. Mandwa turned out to be a jealous man, “a monster” and a wife-beater, who nearly sent her to her grave on four occasions.

“…it was not to take long, about three months down the road and the man proposed to marry me and without a second thought, I said yes. I was entering a marriage that was as ugly as ugly can be. Where had the brilliant, confident, intelligent, smart girl attributes gone? …,” Opolot writes in the autobiography published in 2018 by G.W. Publishing Company in Kampala.

First signs of trouble

Her father and mother talked to her and tried to discourage her from marrying Mandwa.

“..They asked what had become of me, what had become of their daughter who had made a history of success in the village, how were they going to face the new reproach I was about to bring to them by marrying a witchdoctor? …,” Opolot writes.

Even when Opolot’s clan set a high bride price, Mandwa paid it and, therefore, married her according to Iteso traditional customs.

After the traditional marriage, Opolot was sent off to her new home.

“The weeks that followed saw me being introduced to this way of life. I had to know how to cook my husband’s food – anything that fell to the ground was never to be back either on the pan or on his plate. His fireplace was built with bricks as food must be cooked from above the ground and not the traditional fireplace found in most African villages…”

Mandwa only ate chicken with red feathers and fish. No vegetables from any garden, no fruit except mangoes. He would stay without food for days on end and only drunk water if he went to the water source.

“There were days when the spirits would not allow him to bathe and I had to accept and bear with that for as long as it lasted. At one point, he was instructed never to shave his hair but have it weaved with talisman, and, or a fetish. All his wives were not allowed to give a handshake to other people except him but I was exempted because I had a public life and could not adhere to this rule. I was given a new name – Nakandi, which name I later denounced.”

Mandwa built small huts which served as his alters for his spirits in the village and at camp Swahili in Soroti Town. Patients trekked in from near and afar for consultations and treatment with cows, goats or chicken as payment. Periodically, he would be hired to go and pitch camp in some home away for 10 or 14 days.

Mandwa initially allowed Opolot to continue working in Soroti Town, but he later stopped her when his brutal instincts kicked in.

Physical assault

Everything seemed just fine until the sixth month into her pregnancy. Mandwa slapped and kicked Opolot after accusing her of sneaking a man into her house.

The following day, Mandwa apologised for the assault and said he would never do it again. He confessed his undying love for Opolot, saying even a mere thought of sharing her with another man would kill him. “He promised never to beat me again,” she recalls.

On the second and third occasion, he battered Opolot after accusing her of sleeping with her bosses at her place of work. Mandwa was arrested by police, but was later released.

After each battering, Mandwa would apologise and even when he was arrested by police, he would somehow find his way out. Reprimands by his family did not deter him either.

On the fourth time, Mandwa accused Opolot of having an affair with a man called Mamadi, who lived near her village. “…He pulled out a knife and said I was going to talk and that if I did not, he was going to maim or kill me and go to prison. I blamed myself for being so naïve and stupid for I had the opportunity to run away from this monster but I blew it,” she says in the book.

“…He hit my head with a knife and as I started bleeding, he sucked the blood that was gushing from my wound. I was screamed on top of my voice, until someone kicked and broke the door. It took three men to drag me out but he followed me, beating any part of my body and cutting me with the knife. As I lay down, my father-in-law literally fell on me and covered me with his body, telling my husband to kill him instead but let me go. He pulled the old man away, dislocating his knees and he continued beating me. I was numb because I felt no more pain.”

Mandwa fought everyone who suggested that Opolot be taken to hospital. He later disappeared from his home.

When everyone was asleep deep in the night, Opolot escaped and walked to her parents’ home. Her parents took her to the police. A police doctor examined her at Soroti Hospital concluded that she was grievously harmed. Police charged Mandwa with attempted murder and a warrant of arrest was issued against him.

Mandwa was arrested and taken into custody. On the fourth day, when he was supposed to appear in court, he was released by police. “…when I tried to follow up the matter, I went to see the officer-in-charge of criminal investigations. Unfortunately, he just told me to go and sort out ‘our family issues’ amicably at home.

He told me that surely, I did not want to send my husband and the father of my child to jail. He said good women do not do that and he stood up to show me the door,” Opolot narrates.

More violence

The next time, Mandwa accused Opolot of having an affair with one of his workers.

“My heart was in my mouth because I knew that this was perhaps going to be my end. Immediately he grabbed me by my neck and took me to the house, pushing me so hard that I fell and hit my head on the wall. He boxed me, kicked and hit me with a big stick and threatened to cut me with a knife used for slaughtering cows. I screamed until I blacked out,” Opolot recalls.

“…Realising there was no more movement from me, he thought I was dead. He collected a few of his stuff and went across the lake. Meanwhile, after what seemed like an eternity to those around, I regained consciousness, although my body was still numb with pain. No one would dare take me to hospital. My wounds were bandaged and my dislocated shoulder, crude as it may sound, was snapped back to position by a traditional expert by way of massage...,” she recalls.

The escape

At the end of January, 1987, and exactly seven days after that near death episode, Opolot finally made up her mind to leave her abusive and cruel husband. She fled to Ngora District in eastern Uganda with her two children and young brother.

Opolot’s friends arranged for her and the two children and brother to flee to Kampala. When she got to Kampala, she started hunting for a job and got her first one with Uganda Industrial Machinery. She later worked for Uganda Bata Shoe Company and Unicef.

At that time, the government forces had intensified their operations and put the rebels in Teso in disarray, forcing some to flee to Kenya. Mandwa, who had joined the rebel ranks, was killed in an ambush.

Opolot had to postpone her three-month course in management and administration offered by the Uganda Bata Shoe Company abroad in order to attend her husband’s burial.

“…One prevalent view, especially from my relatives, was that of “good riddance” rather than being truthfully sorry that we had lost someone,” she recalls.

She later joined the UN as a personal assistant to the Unicef Representative in Uganda. It was while at Unicef that her father passed away.

After years of regret and trying to pretend this chapter of life never existed, she had to come to terms with the fact that it would never be erased. Whether or not to share it with the world was another upward hill task, deep inside her was this persistent call that someone needs to hear this near-death story and her return to Jesus Christ.

However, there are many questions that go unanswered in her autobiography. How would an educated woman marry a witchdoctor? Mandwa means ‘spirit’ or ‘spirits’ in Luganda, while a witchdoctor is known as Emuron in Ateso. What was Mandwa doing in Teso region?

About Opolot

Background. Opolot is a 64-year-old mother and a widow for more than 28 years. She is a retired administrator.

Education. She attended Nabisunsa Girls Secondary School in Kampala for her Cambridge Leaving Certificate (O-Level). She undertook a full secretarial course at the New Era College in Nairobi, Kenya, and on part time, studied French as an additional foreign language.

Career. She has worked both in the public and private sectors, diplomatic missions, including the United Nations in Uganda and Kenya.

After her Secretarial Studies, Opolot got employment with several organisations in Nairobi, where she met Charles, the father of her first child, who she delivered on August 23, 1977 in Nairobi. Charles walked out on her and she nursed and raised her baby boy all alone.

Soon, the Kenyans started getting tired of Ugandans in their country.

“…There was an outcry that started small but became so big that the government had to issue a directive not to employ ‘aliens’ unless it was absolutely necessary that the area of expertise didn’t have a qualified person in the country.

“The directive put a heavy penalty for an employer who went against it. Even those aliens who were already employed had to be replaced,” she writes.

Most Ugandans, including Opolot, decided to return home since there was now relative peace after Idi Amin’s regime had been overthrown.

Opolot gave birth to four children. Her son, Brian died in April. She is a co-founder and chief executive officer of Beauty 4 Ashes Uganda, a non-profit organisation advocating and working for vulnerable children, especially the orphans in the rural Uganda.

GENDER-BASED VIOLENCE IN UGANDA

According to the Ministry of Gender, Gender-Based Violence (GBV) is an umbrella term used to describe any harmful act that is perpetrated against a person’s will on the basis of unequal relations between women and men, as well as through abuse of power.

The Uganda Demographic Health Survey (UDHS) 2011, shows that 56.1 per cent of women and 55.4 per cent of men aged between 15-49 have experienced physical violence, while 27.8 per cent of women and 8.9 per cent of men have experienced sexual violence.

According to the Uganda Demographic and Health Survey 2016, women in Uganda are more than twice as likely to experience sexual violence as men. More than one in five women aged between 15 and 49 (22 per cent) report that they have experienced sexual violence at some point in time, compared with fewer than one in 10 (8 per cent) men. Thirteen per cent of women and 4 per cent of men reported experiencing sexual violence in the 12 months preceding the survey.

According to a survey conducted by the Inter-religious Council, the major causes of GBV include increased cases of drug abuse, while poverty leads in economic violence.

The effects of GBV to families include, among others: undermining family stability; the spread of HIV/Aids and other STDs among the married and unmarried persons; unwanted pregnancies; and it increases the vulnerability of women, leading to impoverishment of their victims, families and societies.

The Ministry of Gender observes that GBV remains a public health problem and 59 per cent of GBV is physical violence and has had physical consequences on the victims; some have lost arms, legs, others are burnt with acid and this also causes psychological trauma, while the economy loses manpower.

A recent study by the Economic Commission for Africa (ECA) and UN Women indicated that domestic violence imposes significant costs to the victims, communities and to countries in Africa.

This includes cost to survivors for medical fees, transport and fees for legal and other support services provided by the government and non-governmental organisations, as well as costs related to high absentee rates of girls and women in education, absence in the labour market and productive economic activities as a result of GBV.

The ECA and UN Women study estimated that the direct costs (out of pocket expenses) of Violence Against Women (VAW) in Uganda was at $6.3 million or 0.03 per cent of GDP as per 2012.

Uganda recognised GBV as a serious problem and approved a national policy on the elimination of GBV in October 2016. The government has also passed laws against GBV – but the vice remains a big challenge to the country.