Quality of learning drops in Ugandan schools - report

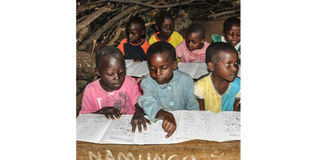

Pupils of Namungo Primary School in Mityana District during a reading lesson last year. PHOTO BYJESSICA NABUKENYA

Findings of a new survey show that quality of education in Ugandan primary schools has continued to decline.

The report indicates that the number of primary school-going children who can read and count has dropped in the last three years.

The findings are contained in a report titled ‘Are Our Children Learning.’ Thirty nine per cent of children who could read a Primary Two text in 2015 dropped to 33 per cent last year.

The figures are not any different in numeracy with only 45 per cent of the surveyed children of Primary Three to Primary Seven able to do an arithmetic of Primary Two level. The rate dropped from 52 per cent in 2015.

Presenting the research findings yesterday, Dr Goretti Nakabugo, the Twaweza country representative, said the learning outcomes have generally remained low since they started releasing their reports eight years ago.

“The percentage of Primary Three to Primary Seven children who could read and comprehend a basic story at Primary Two level dropped from 39 per cent in 2015 to 33 per cent in 2018,” Dr Nakabugo said.

She said special attention has to be paid to Busoga sub-region where the pupils could hardly read in their local language.

But Tororo Chief Administrative Officer (CAO), Mr Dunstan Balaba, who also doubles as chair of CAO Association, defended the community saying for decades, they have used Luganda as the medium of instruction.

Like in the previous report, pupils in the private schools continued to perform better than their colleagues in government-aided schools.

Dr Kedrace Turyagyenda, the Director of Education Standards, who represented Education Minister Janet Museveni at the release of the findings, said the government first concentrated on ensuring every child is enrolled in school which later caused overcrowding that has affected the quality of learning.

“The rate at which our population has grown is incredible. When you have exponential population growth, then you struggle with providing quality education for the children. The rate at which our economy has been growing has not been the same. We have many children coming in and less money available to take care of them,” Dr Turyagyenda said.

The survey was conducted last year by Uwezo, a Twaweza programme, and involved 16, 859 households with 45, 670 pupils assessed.

At least 954 primary schools were involved from 32 districts.

Dr Turyagyenda assured the researchers that their findings will be used to feed into the education sector’s five-year strategic plan for 2020 to improve the learning outcomes.

She, however, implored every stakeholder to get involved in the education of their children.

Dr Turyagyenda asked Mr Balaba how much the local governments were doing to ensure good teaching and learning in their respective districts.

“We still have sub-county chiefs. We even have parish chiefs. What do they earn government money for if they can’t ensure that the few schools in their parishes are having learning happening?” she asked.

She recognised that in their interventions, they had not focused on numeracy and pledged that their efforts will be extended to this area.

“Your report has come right in the middle of what we already know and what we are already thinking through. The sector has been trying to work on the issue of literacy. Unfortunately we have not worked on numeracy. Primary education is supposed to bring out literacy and numeracy. It forms the foundation for the rest of the learning throughout life. When those two milestones are not met, the rest of the levels just struggle...,” she said.

Earlier, Mr Balaba said the money schools receive is little but urged his colleagues to put to proper use the little they get.

Other findings in the report showed that 32 per cent of the children repeated Primary One.

It was not all gloom though as they reported that absenteeism had gone down from 34 per cent in 2015 to 23 per cent. But what was still worrying was the 21 per cent teachers who were on the school time table but were not at school at the time of the survey.

Another 18.5 per cent of the teachers were present but marking books while 5 per cent were doing nothing.