Astles gets caught up in Uganda’s sectarian wars

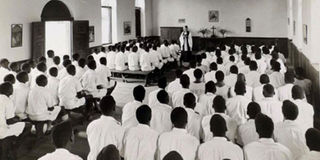

Young boys attend a pre-baptism class at an unidentified place in Kampala. Foreign religion was one of the factors that divided Ugandans prior to Independence and would continue to influence politics and the economy after 1962. COURTESY PHOTO

“ Superficially there was much to encourage the hope that unifying factors would strengthen and Uganda would take her place at the forefront of newly independent African countries. Certainly she had the resources, both material and intellectual, to do so. But beneath the surface, the much stronger currents were working against the fragile tribal alliance.

One seemingly insoluble problem was that of religious rivalry and, like the boundary problem, it had been brought by the Europeans. I have always considered that Kabaka Mutesa 1 encouraged Europeans to come into his kingdom of Buganda during the 1870s, expecting to advance the future prosperity of his people.

What he was unable to foresee was that those same Europeans would bring with them a centuries old quarrel between Catholics and Protestants and that their missionaries would teach their students to hate all other religions. So the benefits of education were accompanied by new divisive influences so deep that they even split families.

During one confusing period, in an attempt to maintain some sort of balance and stability, there were three prime ministers representing each of the three religions, and the religious orders were so harsh that anyone converting to another religion forfeited his property.

The early religious wars of Buganda, a kingdom that formerly had been proudly united, were bloody and died in the disgraceful battles that continued into the next century.

God was no stranger to the Baganda, who had had a name for him in their language for a thousand years or more, and when the missionaries brought the ‘good news’ that Jesus was his son and he had suffered for mankind, they saw nothing extraordinary in their own suffering on his behalf. They truly believed, perhaps more than their teachers, and died calling on Him as they burned on the execution grounds in slow fires with the faggots of wood wrapped round their bodies.

As for the missionaries, how many of them were prepared to go on to the battle-field, amid the spears and clubs, to try to stop the fighting? As far as they were concerned, the protagonists were solely responsible and deserved the consequences.

Religious tensions

By the time Mwanga succeeded his father Mutesa, it was becoming clear that these imported religions were confusing the country and destroying its traditional disciplines and culture.

That was the situation during the elections at independence and the two main political parties had become identified with the Catholic and Protestant religions.

The Democratic Party had the green and white colours of the Catholic Church and was called by many the Catholic Party. The Uganda Peoples Congress did not call itself a Protestant party but made it clear in platform speeches that it was not like the other party with its Catholic following. It was impossible for either party to disguise the connection and as we went into independence, scores of Catholic schools in the Northern Province were burned to the ground.

By 1961, too much had come to depend on birth and religion, including land tenure and admission to schools and hospitals.

The Uganda Peoples Congress was furious when queues of nuns were marched to the polls to vote for the Democratic Party. The Catholics were equally enraged when the European Protestant Bishop of Uganda was found to have taken the leader of the UPC, the young nationalist Milton Obote, to see Kabaka Mutesa 11. The bishop then claimed that the Kabaka had agreed that his Baganda, through his Kabaka Yekka party, would support Obote and not Benedikto Kiwanuka who was a nominee of the Catholics.

All this may be denied today but it is true: I was there and took part in every move. Although at heart I would have liked the Baganda to take the lead, they lost the opportunity by quarrelling among themselves and I became convinced that Obote was the only possible leader at such a critical time.

The violence that Uganda, with its inherent destructive tribalism, was to suffer in future years would have developed much sooner without him.

Even without an interest in politics, I would have had to be blind not to see or grasp what was happening in the months before independence. The distance between my home and that of Dr Milton Obote was the width of the road and neither of us had hedges, walls or fences.

As it was, I had been involved in politics from my earliest days in Uganda and at first I supported the Kabaka Yekka Party because I was one of those who believed that Buganda should have become a separate independent country long ago. After all, many smaller states, even when land- locked and with only half the population of Buganda, had received independence.

Rwanda and Burundi are perfect examples and after initial difficulties, they began to flourish, (though the great difference between the numbers of Tutsi and Hutu was always going to be a potential threat to stability).

Inclusion

However, Obote and the opposition party led by Benedikto Kiwanuka together with the British government had insisted that Uganda must include all the kingdoms. Obote, especially, was thinking as an African and was planning for the long term benefit of the country.

In those days, there was a continual stream of politicians to Obote’s house and my own house also saw a smaller flow of similar visitors, mainly the old traditionalist leaders of the Kabaka Yekka, including Masembe Kabali, Katwe, and Kintu.

All of them complained that Obote was making rings round the Baganda and was not accepting that Buganda had a special place in the independent Uganda of tomorrow. Nevertheless, his main aim was to prevent the Baganda breaking away and he saw that it was imperative to get them involved. So before taking over the country, he formed a provisional government from all the tribes and included many Baganda. I have always been convinced that he managed to achieve this by using Prince Lincoln Ndaula who was one of the Kabaka’s brothers. Ndaula had worked in the British construction company, John Mowlem, about the same time that Obote had been employed by them as a young clerk and perhaps that was when they had met.

Prince Ndaula had been a keen cine-camera operator since the 1950s and had travelled widely outside Uganda. He was a forward looking man and no doubt he understood the dangers of remaining as a separate kingdom. But whatever the reason, he played a decisive part in the alliance between the Kabaka Yekka and the Uganda People’s Congress.

In later years, he came to regret it and spent a considerable time sabotaging the government. I knew him well from his days in Uganda Television and, long before, in the Uganda Rifle Club. It seemed to me that he was born too late: he would have been ideally suited, like so many of us, to the 18th and 19th centuries. So the troubles to come were already apparent in the two houses in Nyonyi Gardens.

Neither the visitors nor the occupants were to have any further peaceful days and most died by violence or assassination. All have been in exile or in political prison and looking back it has been much the same all over Africa. Qualities of leadership and farsightedness are always in short supply and many of those early African politicians were outstanding men. It is very sad to reflect on the way they were removed.

The first fight I witnessed among those aspiring leaders, in the heady days before independence, started outside my home at 3am when, after hours of argument in the house opposite, there was a sudden explosion of tempers and some 10 of the politicians burst through the doors shouting at one another.

They ended up directly under my bedroom window trying to restrain one of the group and shouting at him to control himself. The argument was about who was to be minister for internal affairs. This coveted position was thought to be next in importance to that of prime minister, which was obviously going to be taken by Obote who was a northerner (the Nilotics).

North Vs South

As a result, the southerners (the Bantu) wanted, at the very least, to control the police force that in 1961 was far larger than the army and had always been controlled by British officers. The politicians had not yet understood the potential of the army but understood the power of the police very well. The minister responsible for them would have control over land disputes and be entitled to a red carpet wherever he walked officially. It was an immensely powerful ministry, so here they were coming to blows under my window.

The loudest voice belonged to my old friend Wilberforce Nadiope who was the Kyabazinga of the Basoga tribe, the equivalent of paramount chief. He was a clever and experienced politician and he recognised all the dangers of absolute power getting into the hands of the northerners. As the Ministry for Internal Affairs would also be responsible for the army, he was determined to settle for nothing less.

He also believed that he had the necessary experience for the job having been a warrant officer during World War II and, as he was fond of emphasising, in the British army at that.

But the northerners were equally determined. In the end, he had to settle for vice president of Uganda and also for remaining the paramount chief of the Basoga whose capital was Jinja at the head waters of the White Nile.

Nadiope knew me well and we had always been friends. In the morning after that furious meeting in Obote’s house that was still continuing, he slipped over to my house for coffee, bacon and eggs. In those days, even my garage had been turned into a dormitory for some of the less important men who had come down from the north. I had not yet met Obote but many of his followers were my friends and were welcome guests at my home.

Nadiope, a huge jovial man, had travelled the world and had been enthusiastic about independence for Uganda since the war years. In the early fifties, he often reminded me that it was Winston Churchill who had told them during the war that they would be getting their freedom after it had been won. Clement Attlee, the leader of the Labour Party, had made the same promise when the troops were camped in Hyde Park, London, preparing for the victory parade at the end of the war.

Nadiope was a great character, one of the best, and he loved the British who he felt sure would not delay independence. But his army and cosmopolitan background made him a thorn in the side of Obote. He had not risen quickly through the ranks of the British army by being a ‘yes’ man and his reputation in 1939 with the Colonial Office was formidable.

He had never agreed with me that Obote was really the best man to lead Uganda into independence and on this particular morning after breakfast, while he fed my exotic birds in their aviaries, he confided that he feared disaster lay ahead. He thought that the Baganda, with whom his Basoga tribe had always worked closely, were being fooled by some of their leaders on religious issues and that they were handing over too much power to Obote who was clever enough to outwit them all.

As a great chief of the Basoga, he had become impatient with lawlessness within his tribe just before the war and had plucked out a ringleader who was burnt alive as an example to all robbers and miscreants.

The case had caused a sensation and much legal wrangling. Perhaps only the declaration of war in Europe had saved him from further prosecution in Uganda. He was clearly quite prepared to go to great lengths for his country and no doubt Obote, who knew his history and character, realised that if he had the police and army in his hands, many criminals would not see the courts but only a pile of blazing logs.

But whatever the reason, he did not get the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Defence, which went to Felix Onama, who was a Catholic and from the Madi tribe. Obote, eventually, may have regretted putting the army into Onama’s hands as I will show later.

That day, Nadiope stayed with me for several hours. He loved my birds and small zoo and had sent me many animals needing treatment when he had recovered them from the nets of hunters who were being prosecuted for poaching. I was the RSPCA representative in his area, so injured animals were always sent to me. The giant hornbills with their bright eyes and long lashes invariably amused him and as they pushed their bills into his hand to get at the grapes he was offering them, he lamented that the future for Uganda was going to be

He could see that the days of the kingdoms were over and with them the heritage of the proud Bantu. He was not worried about Obote but about Obote’s cousin Adoko Nekyon, who was known to despise the Bantu and had been heard to talk crudely of giving their beautiful women ‘half-caste’ children, presumably by men of the north.

This had infuriated Nadiope and he said he would stand alone against the northerners and if the Baganda wanted to lose their king, it was up to them but the Basoga would remain firm. It was this stand that got him the vice-presidency of Uganda when he failed to get the Ministry of Internal Affairs but having got it, he realised that he had been tricked. The position had no powers and the bodyguards were able to report his movements. Later, he said to me: “I am like those animals I have sent you: in a net!”

Obote, as the new leader of Uganda, was thus in a situation where his supporters were craving power and maintaining a tribalism he was determined to crush. His dream was a united Uganda and his efforts to achieve this were obvious to all of us round him but were not recognised by those of limited vision of whom there are far too many in Africa. Despite the differences with Nadiope, most of Obote’s body guards were of Nadiope’s tribe and right up to the time of his exile, Obote’s trusted private secretary was Henry Kyemba, another of Nadiope’s tribesmen.

Nadiope’s role

Unfortunately, Nadiope could never really reconcile himself to having a much younger man as his prime minister. I saw him quite often after independence and the conversation always returned to the same issues; that the British had neglected him, that he should have been the leader of Uganda, that he failed to see why northerners were in power or why Uganda should have been created from tribes who were really Sudanese. He knew that I admired Obote but I was always frank about where I stood, which is more that can be said for the new friends he was unwise enough to make.

There had been plots against 0bote since 1962 by men who were not interested in the welfare of Uganda as a nation and who refused to acknowledge the right of the people to choose the government by a free vote. They were also indifferent to the efforts Obote had made, with tireless energy, to travel the length and breadth of Uganda in borrowed vehicles, suffering considerable hardship, to speak to the masses and gain their support to win the forthcoming election: the same election that gave the plotters, through Obote, their own power, their ministries, and their houses and cars. Yet these people were concerned only to take his job and I heard repeatedly the comment: “Who is he? I could do his job better!”

Extracted by Sarah Aanyu

Yesterday’s serialisation was part VII, not part V, as we indicated.

Continues tomorrow