Challenges of providing text books in rural areas in Uganda

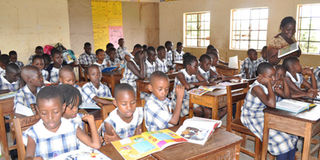

Reading culture. Pupils of Tropical Primary School in Najjera, Kampala read story books with the help of a teacher during the Reading Day in 2018. PHOTO BY RACHEL MABALA

What you need to know:

Series. Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) number 4 seeks to ensure an inclusive and quality education for all and promote lifelong learning. In a five-part series starting today, we explore the importance of storybooks in achieving literacy and lifelong reading as a development indicator. For Uganda to achieve a lifelong reading culture it has to include the storybook on the national curriculum. In this first installment, Bamuturaki Musinguzi looks at the challenges of providing storybooks in the rural areas in Uganda.

On a quiet morning the librarian of the Nambi Sseppuuya Community Resource Centre in Igombe Village, Buwenge Sub-county, Jinja District in eastern Uganda, Mr Isa Maganda, is busy sorting out story books that he is going to transport to Muguluka Primary School under the centre’s mobile library project known as the Bicycle Schools Outreach Programme.

“I have sorted story books which will interest Primary Six and Seven pupils,” Mr Maganda tells the Daily Monitor as he packs Lusoga, Luganda, English, animal and youth story book series in a fabricated metallic box with two mats to lay the books on at Muguluka Primary School.

Mr Maganda then screws the metallic box with one wheel on each side that has a capacity to carry books weighing 75 kilogrammes onto a Mountech bicycle. He mounts the bicycle and rides it towards Muguluka Primary School, about one-and-ahalf kilometers from the centre.

Places that need books

He visits a large number of schools on a bicycle providing a valuable outreach service. The service provides books to more than 50 nurseries, schools and colleges. The same service is also provided to surrounding village communities, hospitals, churches and prisons.

When Mr Maganda arrives at Muguluka Primary School and puts the story books on a mat in front of the P7 class, pupils, one by one walk to the front to pick what they will each read that morning. There is excitement and enthusiasm as some pupils read stories for others aloud in front of the class in English or Lusoga while others read alone.

The 14-year-old P7 candidate, Sharif Muvuma picks What A Country Without Animals! by Ndyakira Amooti published by Fountain Publishers in 1998. “I want to read this book because a country without animals it will not attract tourists. I would wish to see a zebra in a game park,” Muvuma says.

“Story books help me to perform well in English especially in comprehension. I have learnt new words such as karate and a person who practices karate is always fit and healthy. This library helps us to understand some of the challenging questions in different topics. For example, challenges in science and the planets,” Muvuma, who wants to become a medical doctor to help the sick, observes.

Another P7 candidate 16-year-old Justine Ganza picks What A Country Without Trees! by Ndyakira Amooti published by Fountain Publishers in 1998. “I want to read this book to know how trees are useful to us and the environment. Some of the dangers resulting from cutting trees are deforestation and drought,” she says.

The Muguluka Primary School P7 class teacher, Mr Yusuf Kyebambe, is full of praise of the mobile library. “It has really helped us because the national curriculum has been changed to test competencies such as language competence which comprise of pronouncing words, spelling words, reading and writing.”

“So the storybook helps to develop content in various disciplines talk about science, social studies and religious education. Besides English the pupils have to read and comprehend a given subject or task. It also helps kids to be self-reliant in reading, to read for leisure and independently,” Mr Kyebambe, a Social Studies (SST) teacher, adds.

“This mobile library has helped to cover the shortage of set learners provided by the ministry of Education. For example, in P6 we have 235 pupils and the ministry of education has provided only 20 set learners, so even if you were to group them it is impossible to serve all of them. So with the Nambi library we are able to group them to share one set learner to six pupils,” Mr Kyebambe said.

“This is a rural school, where parents can’t afford to buy story books and yet the government provides fewer books. So the Nimbi library comes in handy or offers a solution.

“This outreach is programmed and planned with schools. Kids may have a 40-minute or one-hour break on a school day, and may not have time to come to the library at the centre. So it is better for me to take the books to schools,” Mr Maganda says.

“I sometimes read for the pupils storybooks especially those in the Lusoga language. I also help them translate from Lusoga to English,” he says.

The community resource centre was set up by the community of Igombe Village in memory of their resident, Irene Nambi Sseppuuya, who died in 2002. Irene was an information person. She loved to inform, to educate and to entertain.

The construction was of the centre began in 2004 and completed in 2012 in order to collect, organise and store reading materials for all categories of users. The facilitators of the centre organise activities aimed at eradicating ignorance, poverty through education, training, and provision of reading and research materials. By providing education and training they hope to enhance practical skills and help users gain knowledge which can help them combat poverty.

Management is still grappling with the inability to effectively inform those outside Igombe Village about the services offered by the centre.

According to Mr Maganda, one of the initial inherence that the centre faced was the ignorance of the parents in the locality. “The first challenge that I have always encountered is all about the level of education of the parents. Some of them have attended school; those who have are drop outs. So they don’t know the value of reading and therefore a library.”

Mr Maganda adds: “They have been asking us ‘why have you set up such a library in the rural area where people do not read?’ They think it is a kind of business for us to make money. When you try to engage them they think we are using their children to make money. They ask ‘How do you benefit?”

“I tried the door-to-door approach to convince the parents and children to come to the centre. Thereafter, the first trick I used was organsing reading tents at this centre. And for whoever emerged as the best reader would receive a prize. So this encouraged many potential young readers to come over here,” Mr Maganda said.

“The second trick is I have used the indoor games such as chess, ludo, snakes and ladders, playing cards, and scrabble, which have really attracted many children here. I also recently started a music, dance and drama group through which I have engaged both the youth and adults in the performance arts,” Mr Maganda adds.

Management started computer lessons, internet and photocopying services to generate income for the centre to pay for power and staff salaries. “But we are not earning much to cater for staff salaries, repairs and maintenance, and electricity bills. As a result other staff members have left and I am here alone to serve all the sections in this centre. As a person with a family to cater for I find it difficult to maintain their upkeep without a salary. I have kept here because I am committed to promoting the reading culture,” Mr Maganda says.

Mr Solomon Sellu, an author says, “A mobile library can also be used to refresh a school’s resource collection by issuing of block loans. This model of library is operated from a central library/depot of resources, such as regional or district education resource centre.”

“The mobile library service was initiated chiefly to alleviate the demands for library service at the main libraries by reaching out to the general population with the sole aim of providing accurate and current information to meet the needs in rural schools,” Mr Sellu adds in his paper titled The Role of Mobile Libraries in Supporting Education.

Research. A man picks out a book from the shelves in Albert Cook Library in Mulago, Kampala October 2018. PHOTO BY RACHEL MABALA

The Nambi Sseppuuya Community Resource Centre also runs another mobile library project called ‘Reading on the Streets’ serving those who regardless of age and social status do not have access to libraries.

“If I am not taking books to a school I may ride to a street, trading centre or bus stage where kids are and entertain them with books to read for a short while. When I ride into a community the kids are attracted by the noise made by the metallic box and they follow me around. If it is in a village I may ask the Local Council chairman to permit his members to read at a given venue. Prisoners in Kagoma Remind Prison prefer reading local language story series and Uganda’s history,” Mr Maganda says.

Constraints

The long distances that users have to trek to the centre and another challenge in the rainy seasons where roads are impassable. Mr Maganda says he prefers a motorcycle to transport the books.

The director of Nambi Sseppuuya Community Resource Centre, Mr Justin N. Kiyimba says the majority of parents in the rural areas cannot afford to buy storybooks.

Mr Kiyimba says shortage of manpower has also limited the centre’s ability to have more children in rural areas access story books that they can read at their own leisure.

“There should, therefore, be commitment on the part of the government of nations, educational administrators, librarians, and national library administrations, in order to achieve quality and sustainability in the development and improvement of mobile library services. Only through their active participation will mobile library services transform the teaching and learning process in education,” Mr Sellu says.

CHALLENGES

Mobile library. Mr Sellu lists a number of challenges faced in operating mobile library services which include, among others, lack of resources, space and trained librarians, and financial constraints.

Resources are limited and there is a chance that the appropriate resources could be selected by another school first. Mobile library is medium is size and referral in nature and most times can accommodate less than fifty (50) users at a time. It also lacks certain facilities such as the bibliographic instructions and the library catalogue which are the keys to the holding of the library, Mr Sellu observes.

In tomorrow’s edition, we look at the challenges of providing the storybook in a city setting like Kampala.