Opige’s left leg was buried at his home

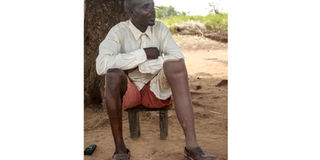

Victim. Simon Opige sits under a tree. PHOTO BY OKELLO STEPHEN.

What you need to know:

Mr Opige is just one of the estimated 12,000 victims of exploding landmines and abandoned bombs during the two-decade Lord’s Resistance Army insurgency

His leg was blown off by a landmine at age 21. Today, Mr Simon Opige, 38, has 16 children to care for through tilling land for sustenance. It is a heart-rending experience that makes anyone shudder at the imagination of going through it.

Mr Opige is just one of the estimated 12,000 victims of exploding landmines and abandoned bombs during the two-decade Lord’s Resistance Army insurgency.

Mr Opige braved the insecurity to do farming during the insurgency which displaced about 1.7 million people from their homes in northern Uganda to Internally Displaced Persons camps by 2000.

Guns continued to rage villages near the camp in Alero Sub-county in present day Nwoya District.

“It was from that garden behind that big tree where we had a garden. They [LRA rebels] had cooked in the compound and passed though the garden. We did not know that they had planted land mines in the garden,” Mr Opige recounts.

He adds: “It happened at 9am on September 9, 2003. I did know see it [landmine]. I became unconscious. I only woke up to find myself at St Mary’s Hospital Lacor. They told me that I had been hit by a landmine. I stayed at the hospital for one year and three months. The operations were not well done. At times they sent me back for another procedure.”

Mr Opige remembers his left leg was buried near his home in Alero. He says the wounded part towards his thigh was rotting.

“Some of the fragments were in my lower abdomen. They were removed but the splinters in the left side of my head have not been removed to date,” he said.

Mr Opige returned to his village about 17 years ago. However his physical rehabilitation has been a long painful journey like most survivors.

Since his only means of livelihood to feed his family is farming, Opige works twice as hard to fend for his children. Whereas he has gone back to his ancestral land to reconstruct his shattered life, he has had the trouble of changing his artificial limb since it was first fitted about 15 years ago. As his body grows, the stump can no longer fit in the artificial limb.

“The only assistance I got was from AVSI in terms of entrepreneurship is training. They gave me cooking oil, beans, and maize. And they have been supporting me to get artificial limbs since 2005. I have changed my limbs 10 times but I have not paid a single penny,” he says.

Since he has been growing from the time of the amputation, his skin around the affected limb has been shrinking. Mr Opige has had more hospital visits than he can remember.

At St Mary’s Hospital Lacor, the administrators could not readily provide data of landmine victims treated at the facility in the past five years.

However, Dr Martin Ogwang, the hospital administrator, said landmine victims have been reducing overtime although they occasionally receive fresh cases during the season when people start farming.

The hospital has been involved in treatment of the casualties and correctional surgeries for most of the victims in the region during and after the LRA insurgency. It works closely with the army to bring victims to the facility.

Dr Ogwang says they receive four to five severe cases a year.

“When you are hit by a landmine, usually the leg suffers. One leg is usually blown off while the other gets injured. The leg which is blown off, usually we don’t have an alternative. We only have to do an amputation to make a stump that the survivor can use and return to normal life,” he said.

Dr Ogwang says the challenge is the cost of treatment. The maximum a person pays for admission and surgery at Lacor hospital is Shs200,000. For revision of the stumps, the charge is about Shs120,000, but Dr Ogwang says most survivors take longer than required to return for review.

“You have been in the village and seen for yourself. People are extremely poor. This Shs120,000 may appear little for people in the city or urban area but it is big money for a poor person who is injured in the village and is also catering for other people. And here the money does not come all the time, the money only comes during harvest,” he said.

He says review of amputated stumps is mandatory for victims to continue using their artificial limbs with ease.

“The only difficult thing is that these prostheses have to be revised all the time because they can wear out. Two, you may have pressure injuries where the stump is fitted inside the prosthesis. And we would ask them to go frequently for the review of the prosthesis. But I know there have been challenges in obtaining these prostheses because they have been mainly donor-funded.

“It has usually been the International Committee of the Red Cross and I also know that ICC has taken over this but it is not cheap to fit these prostheses. Usually on the other limps, there are injuries but you also know that black skin develops very bad scars. So the scar does not allow the knee to extend. Those ones we revise the scars then there are those splinters, bomb fragments that enter the skin of the leg or the chest, this we follow a conservative method, we only treat them when they are bringing symptoms,” Dr Ogwang explains.

He urged government to support the victims with start-ups for income generating activities.

Mr Stephen Okello, a landmine survivor and chairperson of Gulu- Amuru LandMine Survivors Association with 368 registered members, said: “These issues of prostheses, we are depending on development partners. We think the government of this country should put into a budget through Ministry of Health for support of orthopaedic centres so that we have sustainability of these prostheses.”

Since 2008, Orthopaedic Workshop at Gulu Regional Referral Hospital, run by AVSI, has been supporting war victims and donated artificial limbs to more than 300 people every year. The project provides materials while the government pays staff who make the limbs being in a government hospital.

Andrew Obita Okeny, a senior orthopaedic technician at Gulu Regional Referral Hospital, said: “Government takes priority on the killer diseases. Rehabilitation is not taken as priority and in that case, small budget is put on rehabilitation. If the development partners stop their funding to this facility, our work will reduce to making some minor repairs only. Our development partners import and bring those materials here. Our work is only to make and give to our clients for free”

Mr Okeny said they are constrained to help victims who do not fall under the Trust Fund for victims policy, the funder that supports AVSI to provide the materials for prostheses.

The Fund recognises only victims who got injured after 2005 when the Rome Statute that created the International Criminal Court and eventually Trust Fund for Victims became operational.

He, however, does not know the cost of an artificial limb.

Most survivors like Opige can only till land and support their families if they have well-fitted limbs.

The Minister of State for Primary Healthcare, Dr Joyce Moriku Kaducu, said the ministry is aware of the warnings development partners are giving their clients to keep their limbs well if funding stops.

“When you get a project of that nature. It has to end because it has a lifecycle. Government automatically has to take over for sustainability. We are aware of what AVSI is doing. They have done very good work in northern Uganda and they are trying to phase out but in a manner that does not leave a gap. We have been discussing with AVSI to see that as they phase out, we put a budget,” she said.

Since 2008, AVSI foundation in Uganda with support from the Italian Government has produced and given 2,544 prostheses under the Gulu Regional Orthopedic Workshop project in Northern Uganda. The centre provides prosthetic limbs, orthopedic appliances, physiotherapy, counselling and psychotherapy services.

International support

Project. Since 2008, AVSI foundation in Uganda with support from the Italian government has produced and given 2,544 prostheses under the Gulu Regional Orthopaedic Workshop project in northern Uganda. The centre provides prosthetic limbs, orthopaedic appliances, physiotherapy, counselling and psychotherapy services.