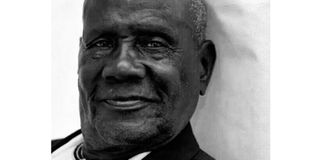

Tribute to UPC strongman Ezra Mulera

Deceased. Ezra Mulera, who was buried last week. COURTESY PHOTO

It is impossible to contemplate the loss of Ezra Mulera without recalling the historical context of Uganda during the 1960s when Uganda was at the height of its powers in spite of a beleaguered politics.

Uganda was then, I am afraid, another country. To say this in public alone today one risks being seen as inconsolably nostalgic for the past but it must be remembered that in spite of the political unrighteousness of the time, the then ruling party of Uganda People’s Congress (UPC) presided over a period of nine years of development that would have staggered any modern African country with unbridled envy.

During that time, Kampala, the city by which we measured ourselves against other East African countries, sprouted its Apolo Hotel, today’s Sheraton, the Nile Hotel Mansion and International Conference Centre, which is today known as Serena Hotel and others.

A nationwide public contest had been held to seek out an appropriate name for the Nile Mansions in anticipation of a summit meeting of Heads of State of the then Organisation of African Unity.

It was during that summit meeting later in 1974 that General Yakub Gowon of Nigeria was overthrown. Already, Obote had impressed the world with a role in mediating the other of African conflicts, the Nigeria-Biafra War.

During that era, apartheid in South Africa was also very topical in world conferences. Africa’s and presidents Julius Nyerere, Kenneth Kaunda and Milton Obote, the elder-statesmen of the call for change in Azania, as Southern Africa was known in the prevailing African political landscape’s parlance, lodged continental dismay at the treatment of Africans in South Africa by the Boers.

Other massive development and international profile projects that Uganda promoted at the time were decapitated by Idi Amin’s ascent to power on January 25, 1971. For some of us, the abortion of progress that event precipitated for our country is still a very sore wound.

Grand projects Obote and his progressively arrogant UPC wished to see as symbols of development in the country included an ambitious multi-storey plan known as Uganda House, itself a monument to the pompous UPC, which was determined to show its achievements in much the same way other African countries did: via building skyscrapers.

There were also growing development dreams of Uganda’s private sector, represented in part by grand plans of the Hotel Equatoria, which, I believe, in its present form and shape, is an incomplete and sorry reflection of the former blueprint.

In the peripheral rural areas round the country, the UPC government built more than 20 hospitals, upgraded schools and built new ones while also starting an array of cooperative societies that ushered in an unprecedented legion of millionaires. Some of the millionaires, it is true, arose from daredevil transport and trade in contraband across the borders with Congo and Rwanda but, on the whole, Uganda was a country that still possessed working political and legal instruments against corruption.

Obote’s UPC was peopled by such intractable supporters of both man and party as Ezra Mulera. Impassioned in life and work in rural communities, they were unwavering in their belief that Uganda deserved to develop and to do so with their own man at the helm. Obote was, unquestionably, that man.

Education

Uncle Ezra was, in fact, one of the finest educated inhabitants of the rural district and, as such, was a leading light in that environment. He and others across the country had been the hand-tools of economic and social development and the firm proponents of Obote’s Common Man’s Charter. People consulted with him before they sent their children to a particular school or cast their vote for a specific political leader or what he thought of the church elders. Yet he was also a man who knew his way in sophisticated urban environments.

Mulera was, at heart, a politician but one with the practical skills of mending unhealthy human bodies. He was, without doubt, a pillar of knowledge and information in Kigezi. A member of the Board of Directors of the then national educational light known as Kigezi High School, where he had been Head Prefect during his student days, Mulera was a readily recognised frame wherever he walked.

He was a man of incorruptible constitution – and there were many of them at the time – and a very humble disposition that, in my father’s reminder of the words of Alexander Pope, concerned itself only with the motto, “Happy the man whose wish and care/ A few paternal acres bound.”

In later years, post-Idi Amin in Obote II, I remember sitting next to him in our village in Mparo as our illiterate relation asked us to help her decipher a medical note, which, sadly, conveyed news of her cancer.

He was still the same gracious and kind man who had, yes, given up Africa’s impossible political dreams but retained an unfathomable seed of the old integrity and absence of pursuit of endless materialism. Dressed in his casual suit and Wellington boots, Ezra Mulera was the epitome of the production of a British missionary education and the priceless cultural values of a Kiga constitution.

While Obote politicised the government’s Civil Service and the Anglican Church of Uganda, he polarised communities.

It was, however, not possible for him to distil entirely Anglican Protestants from Roman Catholics within society. Uncle Ezra, for example, had married a woman from a Catholic persuasion albeit one who had changed her faith.

One Roman Catholic man, who is reported to have abhorred Mulera for his Anglicanism, is said to have paid with the life of his dear wife after he had infused a sorghum drink (obushera) with poison that he saved for him in his house.

Inadvertently taken by his own wife, the man was inconsolable after her death. Whether this is true or not, it shows how seriously we loathed each other for our different faiths.

Mulera was one of many men and women who constituted the framework of UPC and the finest ambitions of the country, which had ensued from the euphoria of independence across the land. His inspirational role in the construction and expansion of UPC and its projects nationwide, first, as a councillor at local level in rural areas and then as Speaker of the District Council in Kigezi, was substantial.

He was a very vocal and aspiring but also self-effacing man in Kigezi who was willing to allow the more nationally ambitious politicians to gain their glorious halos through his spirited exertion on behalf of UPC. These national figures included the towering and omnipresent figure of Sepi Mukombe-Mpambara, who was his close friend and confidant in UPC.

When Idi Amin took over power in January 1971, everything was turned upside-down. I accompanied my father to Kampala to retrieve his belongings from the Uganda Club, the then hotel of Members of Parliament without the means to hold land and property in the capital. There, I met Idi Amin after he announced that the Uganda Club would become an army mess (club).

My father, who knew him very well through their work in government and socialisation at the Uganda Club, introduced me as his young heir, which he rarely did but I believe understood that Idi Amin, as a raw and ill-educated man, would appreciate most the importance of having an heir above everything else.

In the aftermath of that coup d’état, my father predicted Uganda would not survive a military government. As we arrived back at home in Kabale a few weeks after the coup, we discovered the beginning of Uganda’s descent into the bowels of anarchy.

Under Amin

Ezra Mulera, then speaker of the Kigezi District Council, was almost the first casualty. It was well-known that he and others in the local government in Kigezi, were staunch and unflinching supporters of Milton Obote, who had just been overthrown.

Needless to say, none of them was an active politician in that enormously deadly period after the coup. Uncle Ezra turned up at our house in Kirigime, Kabale seeking refuge from political persecution. I do not recall how he had been thrown into a cauldron of fear for his life but it was in a very real and present danger. My sisters were at Hornby Girls’ School, a boarding concern, so the house had the space and silence afforded by two young boys, my brother Edmund and me.

We were made to understand by my parents that Uncle Ezra’s life would be in mortal danger if we so much as breathed a word to our friends about that family secret. For at least the next 8 weeks, perhaps more, Uncle Ezra was a concealed guest in our house while my parents sought to learn where the authority to quash the threat to his life lay.

In several journeys to Kampala and visits to local government and security officials my parents tried to establish the cause of that imminent danger to their relation and friend. Nobody was sure of anything at the time. Fear abounded for us as a family as well because little was known or understood about whether all UPC members would be seen as a threat to Idi Amin.

Later, however, it was clear that local political enemies and their new and growing influence with Amin’s soldiers would prove more deadly than Amin himself.

My father, later, was also rumoured to be a target of persecution but was saved by his former teacher and fellow parliamentarian, Mr John Wycliffe Lwamafa. My father slowly gained confidence from a few members of Idi Amin’s Cabinet, including Mwiri schoolmates, James Zikusooka and Joshua Wanume-Kibedi, of a guarantee of safety for Uncle Ezra.

Ironically, not even they were assured of their own personal safety in the following few months! He has borne the burden of senescence for his generation and now deserves not a moment’s rest but the addition of his personality and charm to the company of angels in Heaven!