‘Dark’ Ash Wednesday: When soldiers attacked Rubaga Cathedral

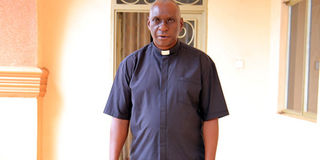

Fr Nkera says to this day, he still suffers from the effects of that day’s torture. Photo by David Lubowa.

What you need to know:

- Yesterday was Ash Wednesday. It is the start of the Easter season as it marks the beginning of Lent. The ashes are meant to symbolise both death and repentance in order to begin Lent in a solemn, humble way.

- This is said to allow people to reflect on their sins throughout Lent before Easter, when Christians celebrate the resurrection of Jesus. It is, therefore, quite disturbing why a group of people would choose such a day to attack a church during Mass and abduct people. This is what happened at Rubaga Cathedral in 1982 as Fr Nkera narrates to Henry Lubega.

“I trained as a journalist because of ‘dark Ash Wednesday’. And I am still living with the physical effects of that day,” says Fr Joseph Nkera.

As thousands of Christians marked Ash Wednesday yesterday, it is exactly 38 years since the storming of Rubaga Cathedral by armed men who forced people attending the Ash Wednesday Mass out of church. The main celebrant of the 8:15am Mass calls that day ‘Dark Ash Wednesday’.

The events

Those days gunshots were a constant night rhyme to the ears of most Ugandans in and around Kampala. The night before the raid at the cathedral, Andrew Lutakome Kayiira’s Uganda Freedom Movement (UFM) fighters attempted to attack Lubiri Military Barracks from Rubaga Hill.

“We had heard the gun fire in the night but did not know that it was fired from the cathedral compound. In the morning, government soldiers found cartridges in the cathedral compound near the statue of the Virgin Mary,” recalls Fr Nkera.

Attack

The three priests: Fr Mpalanyi Katumba, Fr Joseph Nkera and Fr Bwire were conducting a students’ Ash Wednesday Mass when the soldiers stormed the cathedral. There were about 1,500 soldiers and about 200 children in the cathedral with about 100 adults from the neighbouring schools.

“Half way through the Mass, I saw soldiers at the main entrance. They shouted ‘stop’ and I instinctively asked them ‘why’. They cocked their guns and moved very fast to the altar where we were,” says Nkera.

As the soldiers made their way to the pulpit, a stampede ensured. “Children were ordered out. As they scrambled for the exit, the priests were dragged out of the church to the parish offices.

The scene was chaotic,” he adds.

In the office, the three priests were beaten with gun butts and kicked as they were being asked where the guns were being kept. “I was asked to take them were the guns were kept and I told them the cardinal does not have guns,” Nkera says.

All the parish offices were thoroughly searched and lots of property damaged. Also searched was the private residency of the cardinal.

On that day, the entire Rubaga was under search. People fled from their homes to the church for refuge, not knowing it was also besieged. Fr John Baptist Kanyi (RIP), the then Rubaga parish priest, pleaded with the soldiers not to beat the people.

“As people came for refuge they were being harassed and beaten. Some had their identifications torn by the soldiers. Fr Kanyi knelt before the soldiers pleading for them to stop harassing the people but his pleas fell on deaf ears,” says Fr Nkera.

Aftermath

By the time the soldiers left the cathedral grounds in the evening, 60 people had been taken away. “To this day, I still suffer from the effects of that day’s torture. My nerves were damaged and have never healed,” Nkera explains. But the priest was lucky to have escaped with his life.

“Until his death the cardinal was asking then defence minister and vice president Paulo Muwanga to return the 60 people who were taken from the cathedral grounds on that day,” he adds. Both local and international media was interested in what happened. This put Fr Nkera in the limelight.

“Every time there was a press conference the cardinal called me to explain what happened. My constant appearance in the media put me at risk. I had to leave the country and go to Zambia where I decided to study Mass Communication,” Nkera explains.

Church demands apology

The raid at the cathedral happened in the era where communication was at its lowest. The head of the Catholic Church in Uganda at the time Cardinal Emmanuel Nsubuga was away in Kyankwanzi church farm on a medical break.

When news of the raid reached him, he cut short his health break and returned to take charge. He issued a four page statement in which he demanded an apology from the government or else he would not honour state invitations.

In his letter the cardinal said, “I hereby protest in the strongest terms against the godless and sacrilegious act of some members of the Uganda army in violating my cathedral and using military force on, especially the congregation which was attending a religious function.”

“I protest before God as firmly as I am able against the use of the military force in obliging three priests to leave the Higher Altar in their vestments during a solemn act of divine worship. Finally I protest against absurd allegations concerning Kyankwanzi farm where I was staying namely that guerrillas were being trained by me at the farm.”

The cardinal also reminded the Ugandan government under president Milton Obote to respect the Universal Declaration of Human Rights which Uganda had assented to in 1966 saying. “The constitution of Uganda (1967 constitution) article 16 …. ‘except with his own consent no person (i.e Ugandan) shall be hindered in the enjoyment of his freedom of conscience and for the purpose of freedom to change his religion or belief and freedom either alone or in a community with others and both in public and private, to manifest and propagate his religion or belief in worship, practice and observance.”

Citing previous incidences were the Catholic Church had paid a high price at the hands of government forces Cardinal Nsubuga demanded government to own up.

“In view of what has happened and the suspicion aroused, I would appreciate an apology from the government for the insult and the harm done to the Catholic Church of which I am the head. The violation of sacred premises is an extremely serious matter of which I am under obligation to inform the Holy Father. Should an apology not be made I don’t see how I could reasonably participate in any public function to which I might be invited in the future.”

On March 17, 1983, President Obote issued a statement in which he regretted what had happened.

What does lent mean to you?

“Lent is a time for intentional reconfiguration with my life’s purpose. To love God and to love others as I love myself, I work towards decreasing those things which take me away from this purpose. I try to take Christ’s path in preparation for Easter celebration of new life.” Hope Rita Namukwaya

“To me Lent marks the beginning of the Easter season. It is a time for reflection and repentance. Every year, I try to challenge myself by giving up something or trying something new that improves my relationship with God. This year, I want to include reflection into my daily routine.” Grace Nakyanzi

“This period reminds me that I am nothing before God, but dust, and to dust I shall return. This forces me to reflect on how to live a life of purpose and commitment to Christ.” Jane Frances Nabuuma

By Phionah Nassanga