Linking a weapon to the death

It is important to link a weapon to the death in question.

On March 13, 1990, Charles Rwamunda came home at around 10pm and he was apparently very drunk. His mind also appeared to be disturbed. He asked for, and started looking for, his panga. His wife, Gertrude, got very scared and left the house to alert her father-in-law who was nearby. Rwamunda was known to habour a grudge against his aunt, Matilda, who lived close by with her husband, Matayo.

After Gertrude alerted her father-in-law, the two of them went to the house in which Matilda and her husband lived. To their dismay, they found that Malitda’s husband had been hacked to death and Matilda was gravely injured. She was taken to hospital the following day.

Suspect

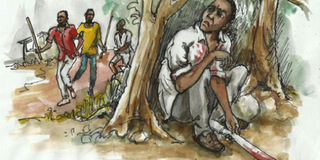

Rwamunda disappeared from his home for about three days after the attack on Matilda and her husband. On the fourth day, he was found in the bush behind his house and had a panga with him. He refused to return home and stated that he feared he would be killed. He was, however, arrested by a group of villagers who took him to police. Just before his arrest, Rwamunda threw away the panga, which was, however, picked by one of the villagers and also handed over to the police.

Matilda died a month later, in the hospital. A postmortem examination was carried out and the doctor attributed her death to raised intracranial pressure caused by an abscess formation in the sagittal sinus. In layman’s language, this simply meant that there was an accumulation of pus in a part of the brain which therefore caused the brain to swell and create pressure within the brain cavity and ultimately, death of the victim.

Tracing movements

Rwamunda was taken to court and charged with the murder of Matilda and her husband. In his defence, given under oath, Rwamunda acknowledged that he came home drunk on the night in question, sent his wife away, went to bed and slept without knowing what was happening.

He told court that when he woke up, he decided to check if his wife was in the sitting room, but instead found his grandfather, who informed him that Matilda and her husband had been attacked and he (Rwamunda) was being looked for. And he told court that when he came out he heard a mob, carrying pangas and spears, saying “there he comes” and this forced him to flee.

He did not know why those who were mourning for Matlida’s husband wanted to kill him, as he had done nothing wrong. He denied that he had any grudge with Matilda and her husband.

Evidence

The irrefutable evidence before court was that Matilda and her husband were attacked on May 13, 1990, and indeed that Matilda’s husband died that day, as a result of the injuries he sustained. There was, however, no evidence of who attacked them. The trial judge relied on circumstantial evidence to convict Rwamunda.

To the judge, the onus was on the prosecution to prove the case beyond reasonable doubt, and satisfy the court that the evidence presented inevitably pointed to the accused as having been the only person who could have committed the crime, and the evidence was not capable of explanation on any other hypothesis, other than the guilt of the accused.

The trial judge accepted the evidence that Rwamunda came home very drunk that evening and asked for his panga and seemed mentally disturbed. The judge noted that after the attack, the accused was missing from his home and went into hiding, rather than attend the funeral of his neighbour, who was also a close relative. The judge concluded that it was Rwamunda who had attacked Matilda and her husband.

To the judge, the accused had, however, been unable to form the necessary intent to murder because he had been drinking the whole day and evening. The judge, therefore, convicted Rwamunda of the lesser offence of manslaughter and sentenced him to concurrent terms of 12 years’ imprisonment. Rwamunda appealed against his conviction on each count and leave was granted for him to appeal against the sentence.

Appeal

One of the grounds of appeal that was raised by Rwamunda’s lawyer was that the cause of death of Matilda had not been proved beyond reasonable doubt; that is, the doctor had not linked the panga, purportedly used to inflict the injuries, to the wounds inflicted on the deceased and ultimately to their death.

The lawyer told court that although there was no doubt that Matilda was dead, the cause of her death was not clear, since she had died almost a month after the incident; there was the lapse of time from the incident to the time of death and there was no evidence which explained what had happened during this interval. There was apparently no obvious link between the panga and the pus formed in the brain, which is reported to have caused the death of Matilda.

TO BE CONTINUED