Prime

Oulanyah’s law that freed musicians to make money

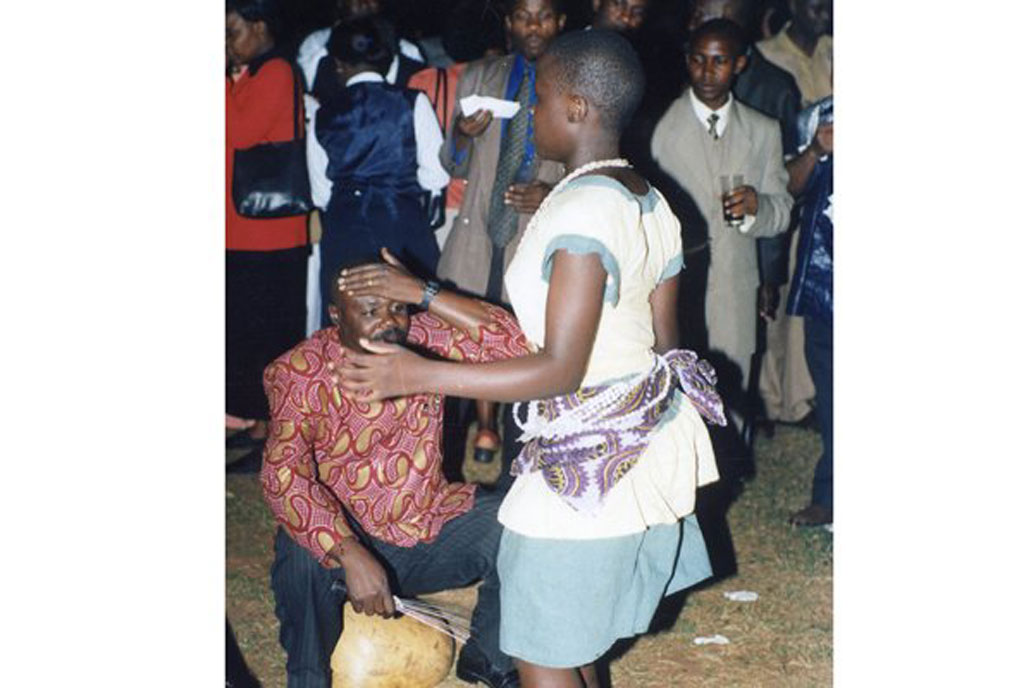

Jacob Oulanyah participates in a traditional dance during a party at the Mayor’s Gardens in Kampala in 2002. PHOTO/FILE

What you need to know:

- Dissatisfied with the working of the law, Oulanyah was due to meet stakeholders in the arts sector before failing health resulted in his death last month in the United States.

He has been widely eulogised for his centrist political disposition, oratory gift and being a stickler.

But beneath the political veneer, Jacob Oulanyah, 56, the former Speaker of the 11th Parliament, who died in the United States last month, was compassionate.

That empathy, coupled with an amiable nature, turned Oulanyah into an attraction for the most unlikely of his constituencies: the arts.

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, Uganda’s entertainment industry, long headlined by mainly Congolese musicians, was young and the country’s musicians unable to assert their rights.

In short, they could harvest concert booking revenues, but not earn perpetually from their creativity.

The end result was widespread local music piracy, and local productions dominating airwaves and television playtime as well as telephone ringtones, but without direct transfer of the revenue to the composer!

Mr James Wasula, an Intellectual Property Rights activist/specialist and former chief executive officer of Uganda Performing Rights Society (UPRS), said in the early 1990s, they embarked on drafting a new Copyright and Neighbouring Rights Bill (CNRB)with the assistance of the World Intellectual Property Organisation (WIPO) and the government of Uganda.

However, after completion, UPRS chairman Kafumbe Mukasa, now deceased, told them that it would take some time before the government could consider tabling the Bill due to a clogged legislative agenda.

Mr Wasula turned to Oulanyah, one of the firebrand debaters on then Radio One’s popular open-air Ekimeeza talk show, which the former moderated.

“I told him about our predicament and the urgency of enacting a new Copyright and Neighbouring Rights Act that would meet demands of the day. The existing Copyright law, for example, was not providing for collective management of rights and did not criminalise infringement. It also did not protect neighbouring rights,” Wasula recounts.

Oulanyah, the Omorro County MP, at once asked for a draft of such a Bill, which Mr Wasula shared around 2005.

Nothing appeared to move until the legislator’s encounter with a struggling artiste in his own backyard.

Oulanyah telephoned to inform Mr Wasula that he had in his city office a local musician seeking money for a Kampala-to-Gulu return fare, because there “was no money in music” despite his music being played on radios.

This prompted the first-time lawmaker to ask for an impromptu meeting with Wasula to expedite seminal discussions about the Copyright and Neighbouring Rights Bill that he tabled as a private member’s Bill. It was, much to the manoeuvre, mobilisation and relief of Oulanyah, enacted in 2006.

“The creative sector owes him eternal gratitude for undertaking the responsibility to table the CNRB and seeing it through,” Mr Wasula said.

On February 7, 2007, UPRS organised a workshop at Grand Imperial Hotel to introduce the CNRA to stakeholders and to start the journey of popularising it among rights’ holders.

Oulanyah, a gifted orator, used his presentation on, reproduction and distribution of music works: The legal aspect, to wow his audience in ways that converted sceptics instantly into copyright defenders.

Dissatisfied with the working of the law, Oulanyah was due to meet stakeholders in the arts sector before failing health resulted in his death last month in the United States.