Prime

When tranquility returned to greator Uganda

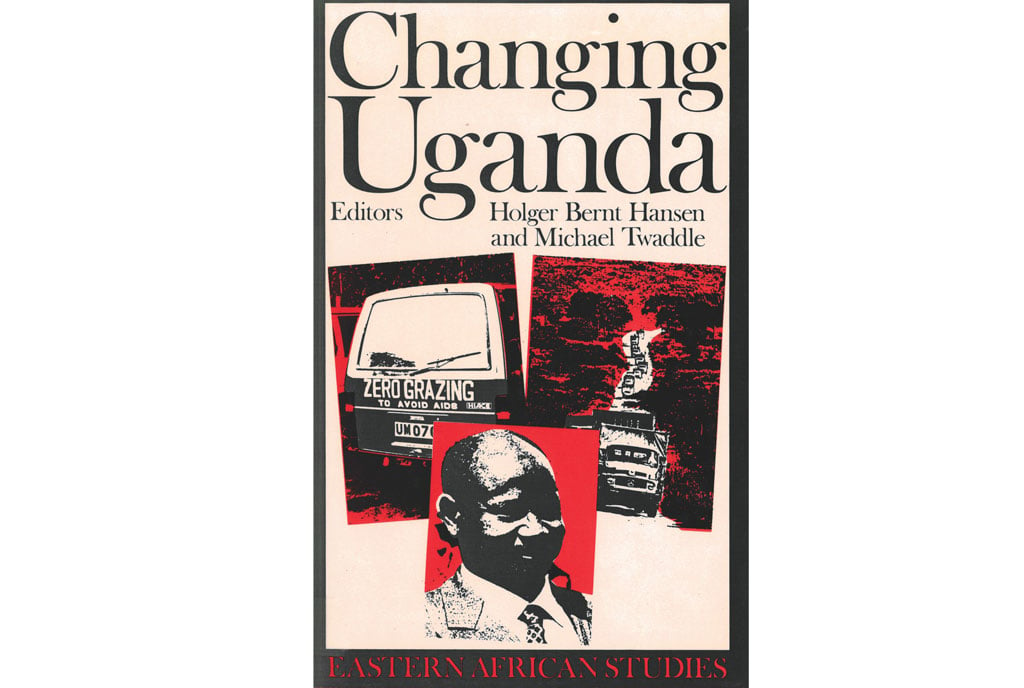

Book cover. PHOTO/COURTESY

What you need to know:

- Book title: Changing Uganda:

- Author: Asan Kasingye

- Price: Shs15,000

- Where: Aristoc Booklex.

This book, entitled Changing Uganda, issues from discussions made possible at Lyngby Landbrugsskole, a school building in Denmark, where 40 delegates sat in September 1989 to discuss Uganda in depth.

The context shaping these discussions was the tranquillity that had returned to a greater part of Uganda. Even as there was still a war raging as the remnants of the military junta of Bazilio and Tito Okello, along with surviving partisans from Milton Obote’s second rule, aimed to put the three-year old regime of Yoweri Museveni to the sword.

This book, edited by Holger Bernt Hansen and Michael Twaddle, comprises 24 essays sprawled across 10 chapters which essentially dot the i’s and cross the t’s to reach a crystalline understanding of what ailed Uganda and what were the remedies thereto.

Against the background of war, a major Ugandan ailment, the National Resistance Army (NRA) troops in Soroti committed atrocities against the local population after two NRA soldiers were beheaded by supporters of Peter Otai’s Uganda People’s Army. Otai was the minister of Defence in Obote II. Prof Dan Mudoola argues for ways and means of Uganda surmounting this insecurity, not just in the short and medium term, but the long term.

Still, in spite of its best efforts, the army was still confronted by rebels such as Alice Lakwena and her Holy Spirit Movement which sought to cleanse Ugandan society of its ills, as perceived by Lakwena.

However, there were external threats with Zaire being in flux since President Mobutu Sese Seko, had allowed a multiparty system in his country in early 1990.

Again, the Rwenzururu secessionist movement based in Ruwenzori mountain ranges straddling the border between Uganda and Zaire was cause for concern to the ruling National Resistance Movement (NRM).

Then there was the issue of the Khartoum government (Sudan) employing dissidents from pre-NRM regimes as militiamen acting against the Sudan People’s Liberation Army on the Sudan/Uganda border.

As for Uganda’s relations with Kenya at the time, David Throup writes in chapter 12: “Nairobi continued to view events in Uganda with grave concern. Every sign that Museveni was strengthening Uganda’s ties with Islamic states, especially Libya, created a mixture of fury and fear.”

Indeed, “Changing Uganda” explains the powder keg situation that surrounded Uganda, on several fronts.

It should be noted that the NRM government was largely perceived to be militarist as opposed to merely being militant.

Museveni, however, did his best to disabuse the world of the misperception.

“The NRM is not a military government. We are freedom fighters who took up the gun as a last resort to fight against dictatorship,” he said.

Beyond security issues, health issues are discussed in chapter seven to chapter 10 with writers such as George Bond, Joan Vincent, Susan Ryenolds Whyte and Tim Allen depositing their worthy instalments of two cents on this matter.

When it comes to education, an interesting argument was presented by Prof Senteza Kajjubi in chapter 22.

He revealed that the ratio of expenditure (at the time) per capita on tertiary and primary education was 300:1.

“It can be argued,” he wrote. “That the free education, food, accommodation and personal allowances [currently accorded to Ugandan university students] are a form of subsidy by the poor to the rich parents [who are able to fund their brighter children through school to university entrance level].”

He then argued that the said allowances paid to university students should be scaled down or simply abolished.

The students were not happy when such reforms were introduced, and were led by then guild president Norbert Mao in a strike which resulted in the deaths of some students.

On the economy, this was the time of structural adjustment programmes in line with the so called “Washington Consensus”, which is a set of ten economic policy prescriptions considered to constitute the “standard” reform package promoted for crisis-wracked developing countries by Washington, D.C.-based institutions such as the International Monetary Fund, World Bank and United States Department of the Treasury. In fine, this book is an excellent reference on the early days of NRM rule.