Prime

Njabala queries toxic cultural practises

An art piece of inverted razor blades on a mattress represents domestic violence. PHOTO / ROYAL KENOGO.

What you need to know:

- Njabala This Is Not How, seeks to retell the Njabala story in a more flexible, contemporary and inclusive perspective, where there is not a singular acceptable way of doing and living for women, but a diversity of choices and decision-making.

Njabala, Njabala, Njabala tolinsaza muko, Najabala. Njabala was a young woman who was married off, but hardly knew how to do any household chores. And in a bid to live up to her expectations as a woman and wife, she sings and implores her mother’s spirit for assistance in her marital home.

Myths naturalise culture by making dominant cultural and historical values, attitudes and beliefs seem entirely natural no matter how unnatural these practices seem to the logical mind.

The story of Njabala is a perfect illustration of how Ugandan society has and continues to use myths and storytelling to reinforce toxic culture.

According to Martha Kazungu, a curator, the exhibition that started on March 9 to April, seeks to bring a feminist reading to the Njabala Folklore to facilitate diverse interpretations to be teased out through artistic responses.

“Njabala This Is Not How is inspired by a Ugandan folklore that features Njabala, the lazy girl, who is represented as an incompetent wife. In the story, Njabala is constantly reprimanded by her mother, who frequented her matrimonial home, to teach her how housekeeping is done.

The Njabala story has a handful of lessons and inspirations to the present-day feminism, and we hope to unfold one lesson for each edition of what will become an annual project,” she explains.

She adds that the exhibition launches a long term campaign, in which we accept the vulnerability of putting ourselves on the front line of denouncing things we have inherited as normal.

“We are allowing to deal with the horns of patriarchy and we are diligent in our implementation, so much that our contribution, in whichever format, is not neutral,” she adds.

Kazungu mentions that the Njabala story has many versions where some facts differ. However, some of the details are maintained as constant in many versions.

“The Njabala story tells of a spoiled 16 – year-old orphan named Njabala who gets married but is unable to fulfil any domestic duties. This leads to an unfolding of events where Njabala is repeatedly beaten by her husband for failing to do domestic work. After days of abuse, she cries out to the ghost of her mother to come to her aid as it is her (mother’s) fault that she doesn’t know how to do any chores. The ghost does come to help and while she performs the tasks, she demonstrates to her mortal daughter how things are done while singing: Njababla Njabala Njabala tolinsanza muko Njabala - Njabala,Njabala, Njabala, do not make your husband find me, Njabala. Abakazi balima bati, Njabala -This is how women plough, Njabala........and she went on to show Njabala the “hows” of housework.

The ghost’s labour goes on for several days to the delight of her unsuspecting husband who believes his beatings have indeed corrected his faulty wife. Unfortunately, one day her husband returns early from a hunt only to find a ghost doing chores while his wife looks on.

Astonished and afraid he raises an alarm, Njabala is accused of being a witch and is chased away from her marital home in a sad ending positioned as a cautionary tale to women everywhere.”

Homeless and penniless, nothing is spoken of what becomes of her inheritance as she is an only child who by all rights should have inherited her parents’ wealth.

“The story of Njabala is a myth but also a reality for many Ugandan women. Speaking from a personal experience of growing up in Eastern Uganda with no biological sister and three brothers, I tasted the remnants of the Njabala mythology as a child. It is 2022 and this narrative has not changed. The lockdown only amplified Njabala scenarios in our lives. Increased cases of domestic violence, 2300 school girls impregnated and 198 forcibly married off as the story in Daily Monitor July on 27, 2020 reports,” she explains.

By inviting Ugandan artists to respond to the Njabala Mythology, Kazungu saw a chance of using art not as a solution but as a catalyst to subvert the repressive roles and rules of living for women in Uganda. Both the fact that it was the responsibility of Njabala’s mother (even in death) to rectify her child’s mess and her reluctance to question the events in her daughter’s life tells how deep the roots of patriarchy have sunk but at the same time emphasises that women have a place in improving their own lives.

However, the exhibition enacts a revised function of Njabala’s mother and instead of telling Njabala how to do, it will tell her how not to do.

“We are interested in interrogating the glorification of suffering in society. This glorification manifests itself in applauding those women who are submissive to the difficult space and society has left them denouncing those who attempt to escape that place,” she says.

Although conditions are constantly changing to allow women emancipation, some aspects of culture such as proverbs and folk tales have plagued the woman. By repetitively listening to these stories, young adults conform to their deliberations hence, their associational patterns, identities, decision-making, and value systems are wrongly formed. Even with casual activities such as speech, women are not free. The “right thing” is to keep quiet.

Kanyo Love by Bathsheba Okwenje

“The title takes inspiration from the Acholi word Kanyo, which means to endure or to be resilient. Kanyo Love is an intimate body of work about love in the aftermath of war as experienced by former forced wives of Lord’s Resistance Army combatants (The Women).

Using love as an entry point, the project explores post-conflict reintegration in Northern Uganda. Kanyo Love consists of a series of works that function separately or together as a comprehensive body of work.

This presentation includes individual portraits of women and testimonies about post-war romantic love relationships and the attendant courtship gifts.” Between 1986 -2006, the Acholi, and other people of northern Uganda, endured a conflict between the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) and Uganda Defense Forces.

A weapon of war, used by the LRA, was to abduct young women and girls and force them into marriage with LRA combatants; young men and boys were abducted and forcibly conscripted as fighters; In 2006, an agreement between the LRA and the government of Uganda formally ended the war.

Little Black Dress by Esteri Tebandeke

This is a short film that runs for 22 minutes. Little Black Dress is a story about a couple that is struggling with infertility and seeks to subvert the tendency to blame infertility on only the woman by creating a scenario in which the man too is not only responsible but accountable.

“I woke up one day to news that the Minister of Tourism in my country, had decided that women’s bodies were to be used as a tourist attraction. He went on to start a campaign coined “Miss Curvy.” To loosely state his word, “we have very beautiful women here. Why can’t we use them to draw more tourists into the country?” Do women’s bodies belong to men? Or society? Do women have a say on what happens to their bodies? And most of all, what would a world where women made the rules and made decisions on men’s bodies look like? What would happen if men stepped into the shoes of women and lived in just a day as a woman? Tebandeke wonders.

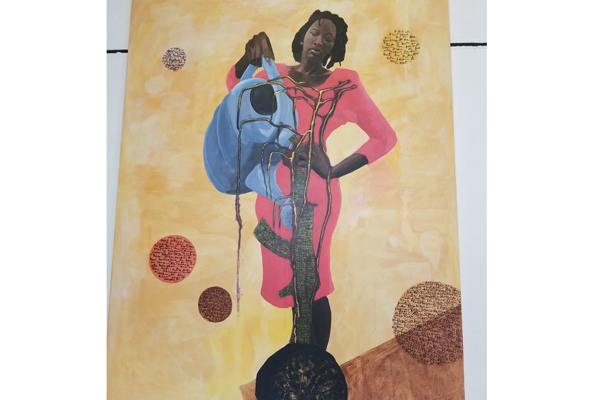

Samba Gown by Sandra Suubi Nakitto

Samba Gown is a performance piece re-enacting and rethinking the bride’s walk down the aisle but using the streets of Kampala as the Church. The performance challenges the institution of marriage as it is the context of the story of Njabala. Explaining origins of the traditions around marriage, the artist hopes for Ugandans and Ugandan women to have the opportunity to establish exactly how and why we fall into this jigsaw. “It appears everything we are taught is to prepare us for the institution of marriage which has been defined as epitome of love between two people. This performance portrays the woman on her wedding day, waking up early in excitement and getting ready as culture would have it. All would be well, and she would get her make-up done and get ready in her beautiful gown. She starts the long journey down the aisle. Along the way a number of things are added to her, words written on her dress, household materials that she needs to use in the home pegged on to her gown. Throughout the performance, the bride is presented happy, smiling and looking like everything is okay,” Nakitto explains.

Lord by Anderu Immaculate Mail

We are looking at a bread of razor blades called Lord. The art work is called Lord and by coincidence I was thinking of the double meaning of Lord because Lord in the religious context is God, that person we respect, but then how we understand God is personal though we speak about him in public.

The same applies to domestic violence, someone will speak about it but the pain the victims undergo can only be experienced at individual leave.

The razor blades are inverted on the mattress and this shows the pain of domestic violence. The mattress serves as a symbol and record of their trauma. A mattress, which usually signifies rest and comfort has been tainted through sexual assault, the mattress, as externalised representation of pain. These are things that do not make headlines until someone is dead.

Lord seeks to make us imagine or even feel the pain that surrounds sexual abuse, the kind of pain which is more often experienced by one person and in silence.

The kind of pain which cannot be talked about in public, just like that. It is embarrassing to speak about it. How will it be heard?

Silence, by Watsemba Miriam

There is a subliminal belief that a woman has character issues that provoke men into abusive actions. She probably resisted, was disobedient, seductive, and suggestive or spoke up to a man. This vicious cycle of indoctrination is passed down from generation to generation and as such breeds environment for silent torture, suffering and abuse.

The photo story is a representation of the stories of women and girls who have suffered at the hands of their lovers ending up with both physical, emotional and mental damage. The goal is to create a collection of photos sharing stories of women who have suffered physical and sexual abuse in intimate relationships under the blanket of silence that is held as a badge of honour and justification of the strength of a woman.

The photo story seeks to help former victims know that they are heard, seen, understood and that their truth is valid. I seek to reach the right audience that would in turn take relevant action on the issues of physical and sexual violence especially for minority groups. Silence is not always the solution for women as culture has taught them, Njabala this not how! Silence is not Okay.

Stella’s Goat by Pamela Enyonu

The work is a tongue-in-cheek critique on patriarchy’s obsession with virginity. Among the Baganda, when the bride-to-be is proven to be a virgin, her close relatives, particularly the brother, are gifted with a goat to serve as a token of appreciation for preserving the virginity. The norm is too entrenched that both virginity and a goat are referred to with the same word “embuzi”.

“Because of this practice, girls are closely herded lest they lose their “goat’. It is as if the ‘goat’ is more important than the girl. It is another case of the patriarchy benefitting from women’s labours,’explains Enyonu. The responsibility for the girl child to preserve their bodies for their husband is still prevalent in many societies in Uganda.

Wake With me by Sarah Nansubuga

It is a portrayal of a folklore story from Kampala, based on the popular folktale story entitled: Nsangi and the Ogre. The performance is an exploration of the metaphorical loss of cultural identity through the literal loss of a family member, and the journey through storytelling as a method to reclaim or preserve what was lost.

The performer engages poetic language to play the role of narrator while using the body and familiar objects from home. Wake with Me is a work in progress, and the creator is ever seeking new avenues of exploration and expression in her artistic process.

“Our stories are representative of our cultural identity. As we continue to develop as a nation, some of the cultural practises are at war with our mindfulness. This war is exciting and multi-faceted, and it is my hope that Wake With Me can grow to not only portray the stories as they are, but to explore this complex relationship in a meaningful way,” Nansubuga explains.