Prime

‘I do not have dreams; instead I have visions’

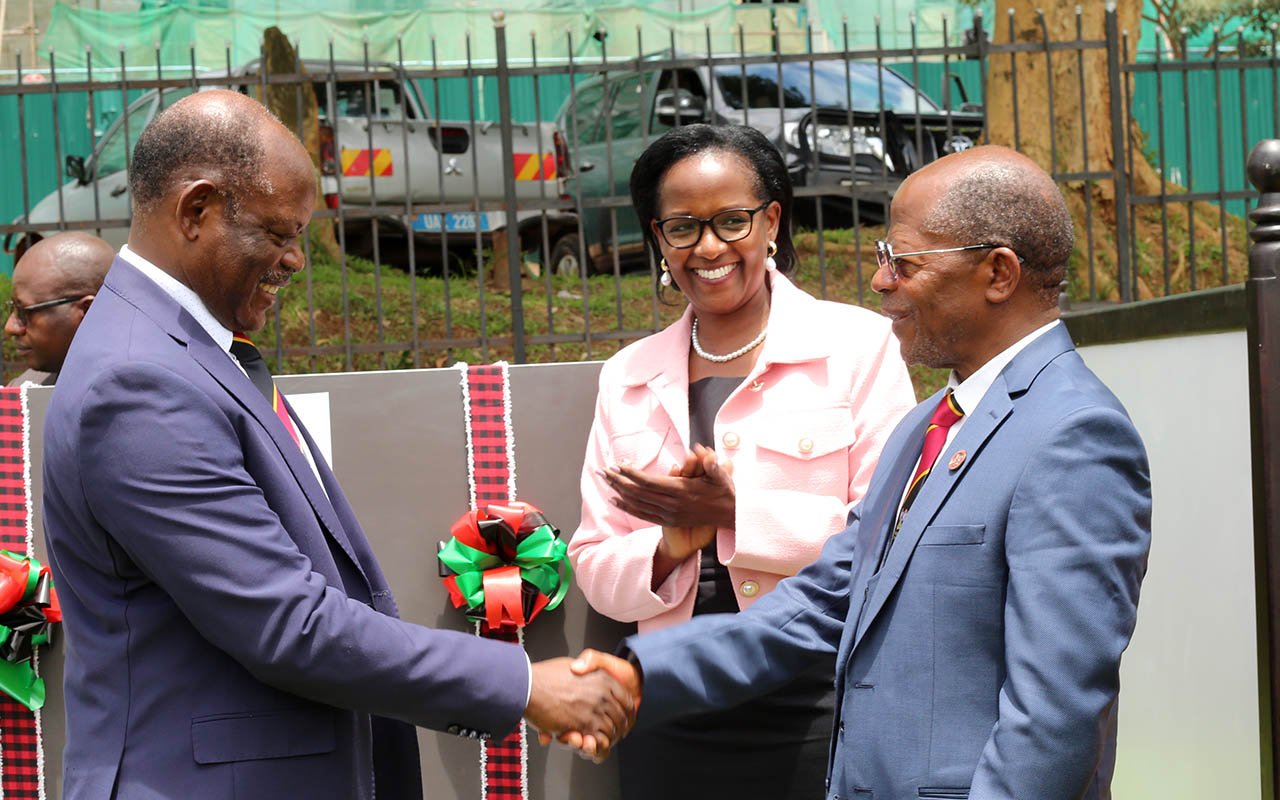

Driven by passion and his parents’ love for communities, Mwalimu Musheshe walked in the same footsteps and today he is an educationist, farmer and agricultural engineer. Photo | Courtesy

What you need to know:

- Mwalimu Musheshe. Driven by passion and his parents’ love for communities, Mwalimu Musheshe walked in the same footsteps and today he is an educationist, farmer and agricultural engineer. Musheshe is currently the vice chancellor at African Rural University, a female championed university located in Kagadi. He shares his career journey and ideology to bring change in communities.

What drives you?

My background; my parents were leaders and entrepreneurs. I grew up seeing a community of friends at home, so at school it was not surprising that I was always occupying leadership positions.

Mwalimu is Kiswahili for teacher, is it a nickname?

No, it is my real name. Many people think it is a title. My parents gave us names such as Bahati, which means successful and my other sibling is named Tabu, and he is always getting into trouble. I was named Mwalimu and I am a teacher.

Tell us about journey in this career.

While in secondary school, I was lucky to attain a scholarship from Tooro Kingdom which partially helped me study at Nyakasura Secondary School. My parents were not there, so I had to struggle for fees by working at the school.

One day while reading in the library someone called Mary Conel had a card in one of the books, so I wrote to her about my challenges and she reached out and supported my studies. I later joined Makerere University and pursued a degree in agricultural leadership. I was in the student guild in the tough times of Obote and I got arrested for opposition politics for 14 months and I went on to start community work in Kahunga.

Why focus on the girl-child?

My mother was an inspiration. She never went to school because it was out of question for girls then but she was a brilliant lady. I learnt a lot from her. Imagine carrying child for nine months without complaining, being a first food store for a child when they are born, checking their temperature when ill, fetching garden herbs and feeding them to recover as well as planting the food and selling it. For me that is a resource for transformation that needed promoting.

What was the situation like in Kagadi before you put in place the initiative for women?

In 1988 when doing a survey with some friends and professors from Makerere, we failed to reach many villages and evaluated if we should work there, which everyone disagreed to because poverty is all over but that of Kagadi stinks.

However, those reasons are why we actually had to start up in Kagadi. There were also concerns on religious divisions and witchcraft, which we developed a new attitude to and took it as a science we needed to investigate. It is here that I knew we would tell our story. From a development perspective, the place was perfect for us.

How does your programme impact the girl-child?

If you look at the traditional structure of family, we have man as the head, so poverty and wealth is determined by him, then we have the mother, then the boy and the girl at the bottom. Our education system is turning that around; we bring one girl from a poor family to transform their homesteads. Our curriculum is centered on mindset change and enabling people understand poverty is not biological but social economic constraints. It is impactful because the girl learns and the parent learns with her to take change back home.

What is your dream for the girl-child in Kagadi?

I do not have dreams; instead I have visions because you can create it and work towards it in a specific period. We have our mission statement where we need an education that is practical but should be in an African concept such as that in East African anthem where we talk about cooperation, traditions, farming and more.

What challenges have you encountered along the way?

It was a bit difficult given the setting to share insights on mindset change.

What is next for you?

As Africans, we should use new technology to revive old knowledge and skills to make it better.

What is your advice to other professionals to take the sector ahead?

People talk about good things but where is the practice? We need more people working with concepts and not using words.

Building ideas...

I enjoy a good book read. Reading books is a stimulant if I want to rest, tell stories and listen to stories. However, books are not meant to make you but to validate what you know, some books may trigger a new path of thinking. If you read a book for a solution, you are in trouble.