Arrested on duty but spirit left unbroken

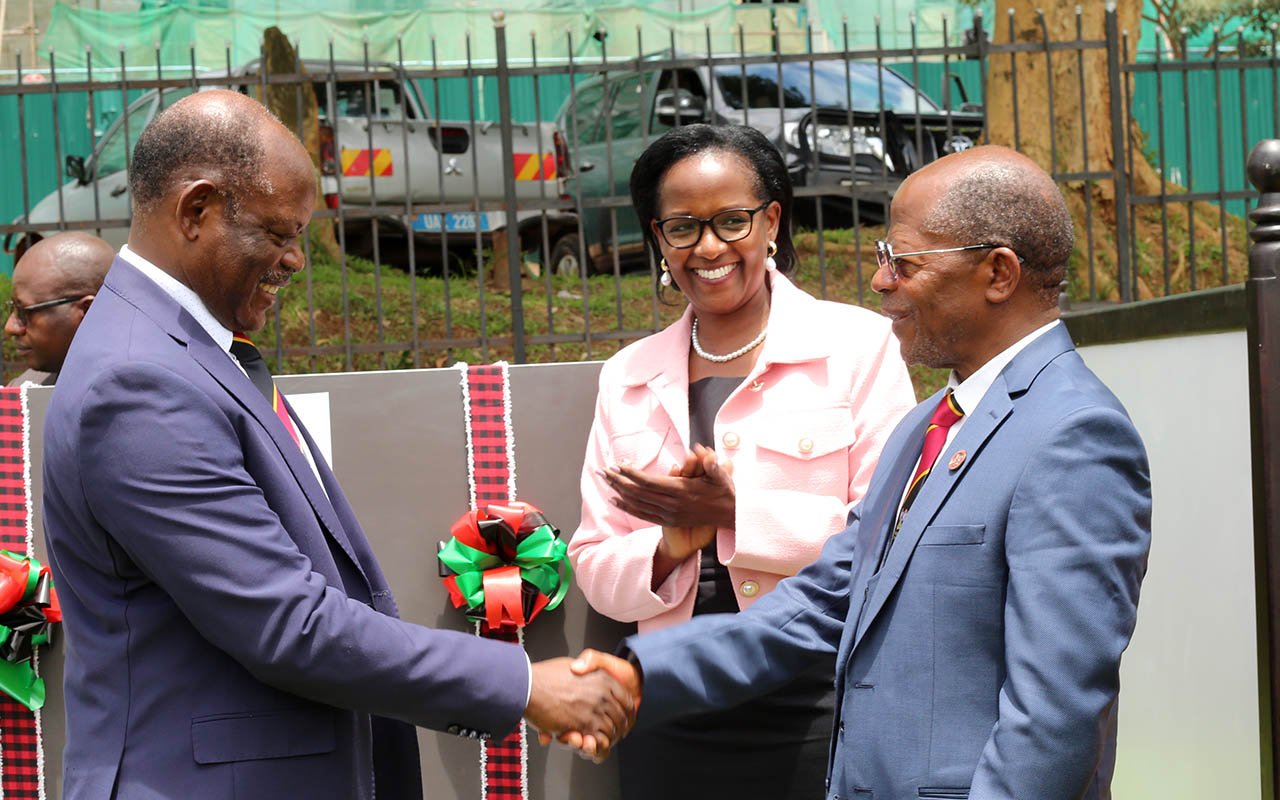

Moment. The writer in conversation with the operation commander of the day as his colleague looks on in Kalangala. PHOTOS | ABUBAKER LUBOWA

What you need to know:

- The plight of a journalist: Following a campaign trail during elections started out exciting until we had running battles with security forces. Derrick Wandera writes about his experience in Kalangala District.

December 30, 2020. The day I was first arrested on duty will remain a turning point in my journalism career. Being arrested and bundled up on a police patrol truck would have been bearable but not this time.

When the team of journalists realised that the police was driving presidential candidate Robert Kyagulanyi Ssentamu, alias Bobi Wine and his campaign team from the landing site in Kalangala towards Kalangala Town which is about 26 kilometres away, we rushed ahead of them to take strategic positions close to the helicopter (chopper) for the best shot.

Soon, despite the heavy security deployment, a truck carrying a team passed by as they chanted songs of Bobi Wine and, “People Power, our Power”.

About 15 minutes later, police patrol trucks at breakneck speed sandwiching a police mobile prison van, commonly known as Nalufenya car, arrived. Therein was Bobi Wine.

Cameras clicked away before the police started lobbing teargas and sound bombs to disperse the supporters. One of the military officers, less than 30 yards away from a group of seven journalists turned and lobbed a teargas canister our direction. We dispersed and regrouped close to our cars.

Fishy time

Meanwhile, the commander of the operation who wore a counter-terrorism police uniform, walked towards us. He grabbed Richard Kalema, a journalist at Ghetto TV, took him away and ordered him to sit down. The rest of us moved away as the same officer returned and took away Culton Scovia Nakamya of BBS Terefayina. They had a brief chat, and he asked for her identification before letting her go.

It felt like we had an informant among us. About 30 minutes later, the commander whom I later learnt was called SSP Bilal Keke aka Blaze, and two other armed counter-terrorism officers donning bulletproof vests walked towards us. You could tell they were about to summon someone else.

When I raised my gaze, a mean looking figure stood before me. He held me by my collar, pushed me and I almost tripped. He put his arm around my shoulder asking me to come along. We reached the spot where the other journalists were seated and he ordered me to sit.

“Are you Wandera Derrick of Daily Monitor?” he asked softly.

“Yes.”

“Give me your ID,” he demanded and I obliged.

“Good,” he said. He bent and started interrogating me. He first demanded to know why I had been profiling the officers. He also took my phone and started inspecting it saying he wanted to be sure I was not live streaming the events.

A call interrupted him and he excused himself. He left briefly and returned with a freelance journalist, Dorothy Doreen Nalumansi who works for an international television. Nalumansi was bleeding from her nose and mouth. I offered her a handkerchief to clean her face.

We sat for a few minutes but Blaze paced and did not take his eyes off me. “I know you are recording me and you will write another story after here,” he said, handing me back my phone. He moved a few metres away but in a split second, returned and grabbed my phone again. Something about my phone seemed to bother him. The time he gave it to me, I had missed a number of calls from high-ranking security and government officers. I could not dare return any of their calls.

When Blaze returned, he said I had put him in a difficult position and the only choice left to me was to break my phone. He handed it to me and ordered me to break it. I resisted a bit but he became more aggressive and reached for his gun. My heart skipped a beat, I thought about my young family and my parents. Losing a phone was no big deal to me, so I broke the screen and gave it to him.

“Give me your memory card,” he bellowed. But my phone does not have a provision for that.

“Have you flown in a chopper before?” I answered in affirmative. He added, “You are going with your man to Kampala.”

He received orders that we (with my colleagues) had to be taken to the waiting patrol car and be driven to the police station.

Inside the cells

While the four of us; Nalumansi, Kalema, and another person whose name I did not get, were waiting to be driven away, the chopper engine rumbled.

Nalumansi sobbed while whispering to me about how scared she was. At the police station counter, her eyes got wetter but I consoled her not to cry anymore. They led me to the men’s cell. Of the four of us, only the two of us were not handcuffed.

On entering a small room of about 15 by 12 decimals filled with more than 26 people, they were shouting and swearing. Most of them handcuffed, demanding for the removal of the handcuffs. The only place with space was next to the toilet whose door did not lock. It could not flush, perhaps there was no water. My fellow inmates told their friends not to go for “long calls” until there was enough water.

At some point I couldn’t breathe, I pushed my mask up in vain.

Most of the people from Bobi Wine security team had seen me on the trail, they asked why I had been arrested yet I was a journalist. Others hit the door hard asking the officers to remove handcuffs until the door lock broke.

Tight. Security forces take position before presidential candidate Robert Kyagulanyi arrived in Kalangala.

After more than four hours of detention, I grew pessimistic about being released. I looked around for someone to lend me a phone so that I call my parents because they did not know my plight.

I called my father, a retired police officer, because I knew he was familiar with the place having served there until 2018. I then called my mother before phoning my wife.

The pleas

As I was still making the calls, the officers called people to be transferred. I pleaded that I was a journalist and did not know why I had been arrested. The Regional Police Commander (RPC) saw me and asked the officer in charge of the station to release me.

The corridors of the police station were a beehive of activity and the air reeked of human sweat. A light-skinned female constable stood at the door of her office ticking off the items that I had left before I went in. I picked my press vest and helmet, among other items. As I was heading out, another officer held me by my trousers, and took me out but the OC came to my rescue and told him to release me because I was a journalist.

Free at last

Time check, 7.45pm. I stood in the middle of a road, looked left and right. There was neither bodaboda nor a car. I had to travel 26 kilometres to cross to the mainland by ferry then go to Masaka.

At some point, I toyed with the idea of returning to the police station to seek shelter because I had no phone or money to pay for my bodaboda fare. For more than 30 minutes, I stood still and voila, a motorcycle came by and I asked him to take me to the ferry.

“The ferry crosses by 6.30 pm,” he replied.

However, he made phone calls and bore the good news about a ferry that was about to dock but we had less than 30 minutes to catch it. My next request was to use his phone to place a call to any random number off head, he obliged. I called, my colleague, a photojournalist on the trail, Abubaker Lubowa. I informed him about my release and that I was on a bodaboda, he assured me they would wait for me.

“On this day, Derrick was meant to watch my back but when I realised that he had been taken, I was not surprised. Many of us had been threatened and expected more arrests. I knew he would be released because I am confident of his personality,” Lubowa says.

My supervisor, Tabu Butagira called to comfort me asking me to keep calm. The murram road was narrow and dark, it went through a thick bamboo forest. We were in time for the ferry. It is from there that I learnt that there is no story worth dying for thus, we have to always mind our safety first. I also felt the solidarity of my colleagues after their noise on social media for my release.

Others say

Ali Mivule, NTV journalist, , “Leaving Kalangala without Derrick Wandera was a blow to our morale. We had faced most job hazards together such as teargas, bullets, scuffles with the forces but, he was one person who could bring back our smiles. In fact, he cheered us up in times that we were about to give up on our duties. ”

Daniel Lutaya, Journalist NBS TV, “Wandera is principled and professional. On many occasions, he urged us to sound out more sources in our stories. He would keep records when all of us had put down our cameras and often scooped us. I was shocked to hear he had been arrested but it didn’t surprise me that material time because I had also suffered brutality and lay in hospital.”

Culton Scovia Nakamya, BBS Terefayina. When Derrick was taken, we all felt insecure. I thought they were going to take me again. Every journalist thought the same. Armed security officers surrounded us but did not say anything to us. Our surroundings were like a battlefield. Nobody could take pictures or even pick a call until Kyagulanyi was airlifted, then we had to rush and catch the ferry but were worried about Wandera in police cells. Different stakeholders were involved and thankfully, Wandera is a team player. He is courteous, and prioritises the safety of his colleagues.