Prime

With offcuts, Nabukenya has turned life around

In this photo combination created on January 9, 2021, Hellen Nabukenya is seen stiching a cloth. PHOTO/ EDGAR R BATTE

What you need to know:

- Stitching away for better. Hellen Nabukenya, a graduate of decoration and styling from Kyambogo University, collects offcuts from tailors and seamstresses in Kiyembe lane.

- No one knew Nabukenya would use this waste, to turn around lives, writes Edgar R. Batte.

“I have known Nabukenya for over 10 years. I have witnessed her growth and transformation not only as an artist but to when she became a mother. Her practice is not separate from her life. Her knowledge and transformation of textiles into installations is similar to the conversations you would have with her on a daily,” Sheila Nakitende writes about her fellow artist, Hellen Nabukenya, adding that her success is anchored on her passion to empower fellow women through her practice.

A graduate of decoration and styling from Kyambogo University, Nabukenya uses waste material to create art pieces, some of which have gotten her continental recognition, and beyond.

Starting out

Her mother introduced Nabukenya to textile while her aunt showed her how to stitch. When she was older, Nabukenya redirected her cause – to use the waste cloth materials to make art installations.

As such, she became a rubbish collector, of offcuts in Kiyembe, an area in Kampala City centre with many tailors. She is often mocked by the tailors who cannot comprehend why she dedicates time to happily collect the ‘waste’ into sacks. The curiosity followed her home where women looking to offer menial labour, such as washing clothes or simple domestic chores, would wonder why their employer picked interest in heaps of rubbish.

She explained to them that the offcuts were valuable and as they observed, Nabukenya went on to turn them into beautiful items. And for the while they stayed around, they asked to be part of her innovative endeavours.

Naturally, as she went about stitching, the women would share about their experiences; struggles. As the saying goes, a problem shared is a problem halved, within the circle, they would share solutions too.

Concerted effect

The communal aspect was one she saw while growing up. Her mother and aunt always invited friends home while they stitched or sewed. So, women coming together to her home to do chores and later on contribute to her artistic process, was a welcome idea.

They would later get to see the fruits of their concerted, colourful efforts at Art Punch Art Studio which she established with two artist friends, or in printed magazines.

She had created a source of livelihood for them as well as taught them a new skill. Along her journey, people have been drawn to her artistry. Nabukenya’s unique genre caught the eye of Senegalese curator, academic and cultural consultant, N’Goné Fall, who is also a General Commissioner Africa2020 Season, a French initiative to view the world from an African perspective..

N’Goné visited Nabukenya’s studio in Kampala in August 2015.

“Her work, mainly focusing on textile, is often participatory, involving women communities. It is an opportunity for these women to share their stories and the challenges they face. Hellen’s art production is always subtle, large scale, and addresses various issues related to feminism and womanhood,” Fall commented in an email response to this writer.

Chance knocks

Having Fall and the like in her circle has introduced Nabukenya to recommendable opportunities. One such opening was an invitation, along with fellow artist, Bruno Ruganzu to ‘The Quai des Savoirs’ for a three-week residency on the theme “Repair, recycle, reuse to rebuild the future”.

There, the duo which works with waste and materials which they recycle, exchanged ideas with residents, makers of the metropolis- local Fablabs and cultural and industrial players, and created two monumental works.

They were presented during the Rio Loco Festival in Toulouse, France in June. Just like she works with local women from communities in Uganda, Nabukenya found a kick in interacting with women from France and Spain who did not speak English but communicated and understood her artistic instructions and guidance.

Together, they made an installation of 10 kilometres of ropes and cloth, a clear demonstration that art is perhaps an inaudible language that let creativity have its way when people choose to put minds and artistic abilities together.

“That has been the greatest achievement I have made. We achieved putting together an artwork yet none of us understood what the other person was saying. We concentred, shared ideas, and created work that is so practical and touches the soul. In a short time, they opened up and shared. At first, the women asked if we were going to use the machine and I told them we were going to use our hands and manually sew,” Nabukenya recollects.

Women sort offcuts which are later turned into art pieces. PHOTO/EDGAR R BATTE.

Such achievements are a deeper satisfaction to the artist whose dream, from the onset, was to become an artist who does not only sell artworks but one who would make an impact.

Arise creativity

Initially, Nabukenya set out to become a fashion designer but her expression of ideas was thwarted by her conventional tutor at Kyambogo University who did not encourage her creativity when she chose to make kikoy additions to a wedding gown, for a change.

The lecturer declined to mark her work. She did what the tutor wanted but did not drop her ideas. She joined like-minded people- Donald Wasswa and Amos Ssentongo, and started Art Punch Studio.

There, she had the freedom to express herself. Immediately, she started thinking outside the box.

“I wanted to be different from the other artists. I would go to Kiyembe looking for offcuts from, especially women.

They were curious and I told them I was using them for my research and I lived in Kansanga,” she says.

Opportunities and resilience

One day, I invited them to help me on an installation which I named ‘Tuwaye’ after the conversations I had with the women as we went about the work.”

She adds that women come together, there is a lot they can talk about and as they do so, solve problems. When the ‘Tuwaye’ installation was done, she reached out to the Goethe Institute which did not give it the attention it deserved. So, she posted it on Facebook and a curator from Denmark, Eva Skibsted Mogensen, saw it and flew into Uganda to meet her.

The two met and that is how she went to exhibit in Denmark. That gave her resilience to carry on, and to also further uplift women’s empowerment, anchoring her motivation on the notion that once you employ a woman, you empower the universe. She continues to work with offcuts and makes installation, big works that make a lot of meaning.

Some of the challenges the women she works with have shared is especially lack of source of livelihood, lack of access to land, and raising children.

Why the craft

Herself a victim, Nabukenya was not raised with her father from the age of two so she ended up growing up in Jinja.

“He never looked after me and I only saw him when I was at university. That partly pushes me to work with the women, some of whom lie to their children that their absent fathers have bought them stuff and food yet it’s their hard-earned money,” she further explains.

In 2015, Nabukenya was part of Light of Africa, her first professional project on which she represented Uganda in West Africa. It artistically demonstrated how solar energy would work in rural Uganda to enable young learners to read.

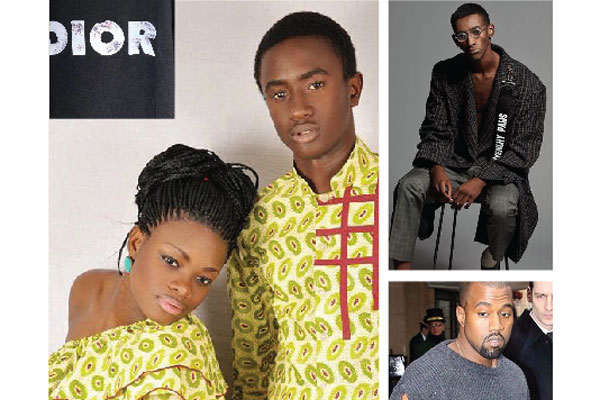

Hellen Nabukenya with her friends show off one of her works. PHOTO/EDGAR R BATTE

She demonstrated this with colourful balls of light that uniquely illuminate. At the time, her inspiration was to raise funds to set up an art studio, a project she’s actualising in Bujuuko, on Mityana Road.

Notable work

Her other notable installations are Kawuuwo (cover-up) and Agali Awamu which she did in South Africa, tackling the racial tension in the rainbow nation.

“It was up on a building and some of the White people who saw it, started crying. They felt healing. They were talking to each other. They said to me that I was bringing back life.”

She says, “I was born an artist. The art I do comes deep inside me. My aunt raised me while teaching me how to use my hands. She used to weave mats and make baskets.”