How native media influenced issues in pre-independence Uganda

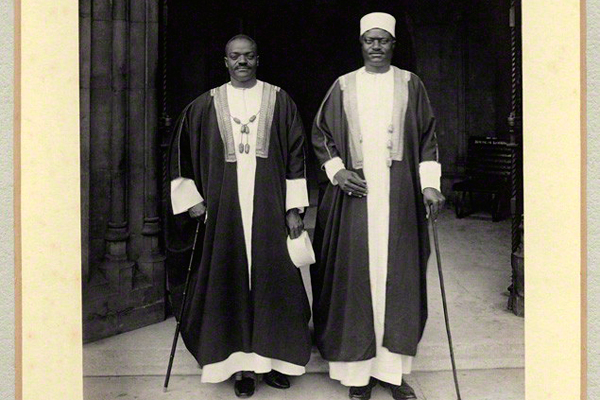

Buganda Kingdom official Ham Mukasa (L) and former prime minister Apolo Kaggwa. PHOTOS/FILE

What you need to know:

- Uganda was the first country in East Africa to have a native-owned newspaper. Sekanyolya was an anti-Buganda establishment newspaper mainly focusing its attack on the chiefs sitting in the Lukiiko and the general Ganda society

- In its January 1921 edition, Sekanyolya made a direct attack on Buganda’s ruling elite.

“Some people despise others because they are chiefs. This is getting to be a common attitude in Buganda. Young men who have tried to get ahead through forming cooperatives and societies are despised by the chiefs. This is splitting the Baganda society,” the newspaper wrote.

The first newspaper in Uganda, Mengo Notes, later named Uganda Notes, was a Church Missionary Society-founded monthly newspaper. It hit the streets on July 1, 1900.

The first African-owned newspaper in the East African region was a Luganda newspaper named Sekanyolya.

It was started by Ugandans working as clerks, teachers and printers in Nairobi, Kenya, under their umbrella organisation, the Nairobi Union of Baganda workers.

Sekanyolya’s first issue came out in December 1920.

Sekanyolya was an anti-Buganda establishment mainly focusing its attack on the chiefs sitting in the Lukiiko (Buganda parliament) and the general Ganda society, save for the Kabaka.

Other groups targeted by the newspaper were the Asian community in Buganda, the missionaries – both Catholic and Anglicans.

Its first chief editor was Zefania K. Sentongo, who learnt printing from the Anglican mission school in Budo.

In 1919, Sentongo and other Ugandans left for Kenya to work for the Nairobi-based Swift Press which also printed Sekanyolya.

In its maiden publication, Sekanyolya drew the difference between the two church-owned newspapers – Ebifa started in 1907 and Munno started in 1911 by the Native African Church (Anglican) and Roman Catholic Church respectively – and itself.

Sekanyolya focused on public grievances that were not covered by the two missionary publications.

“We will not be surprised if our paper is hated since it will speak the truth, which is hard to stick to. Sekanyolya will continue to kill snakes even if some people are using them as food. The feeling to love one’s country is very difficult to have and anyone who has this feeling is very lucky. And those same people who have this love of country always have some grievances. That’s why Sekanyolya should be wished the best of luck,” the newspaper wrote.

The British colonialists gave the newspaper a cold shoulder, while Ebifa welcomed the paper, calling it “the son of Ebifa newspaper” according to its February 1921 edition.

The Catholic-owned Munno cautioned the newspaper against attacking the Young Baganda Association.

In its January 1921 edition, Sekanyolya made a direct attack on Buganda’s ruling elite.

“Some people despise others because they are chiefs. This is getting to be a common attitude in Buganda. Young men who have tried to get ahead through forming cooperatives and societies are despised by the chiefs. This is splitting the Baganda society,” the newspaper wrote.

In its February 1921 edition, it attacked the mission schools for not teaching anything African, and advocated the use of books written by Black Americans.

In an open letter to WTC Weatherhead, then King’s College Budo head teacher, the newspaper wrote: “The Negroes in America learn the use of their hands, they learn everything. You do not teach us anything here.”

The failure for the mission schools to teach what the Sekanyolya chief editor thought was more important drove him to vent his frustration on the Asian community in Uganda who he called a standing “menace of the Indian to native advancement.”

Munyonyozi newspaper

In 1922, the Bataka, who had felt aggrieved in the land distribution, pooled resources and started a newspaper, which was to trumpet land reforms in Buganda.

They called the newspaper Munyonyozi (the explainer) with Daudi Bassude from Sekanyolya as the paper’s editor.

The paper’s honeymoon was, however, short-lived as then Buganda Kingdom prime minister Apolo Kaggwa dragged Bassude and Munyonyozi publisher Joswa Kate Mugema before the Lukiiko for defaming kingdom treasurer Yakobo Musajjalumbwa.

The paper had accused the treasurer of being unfit for the position because he did not know any economics.

The Lukiiko found the two guilty and fined each of them Shs500. However, Bassude and Mugema appealed to the High Court against the Lukiiko’s ruling, but lost.

Prime minister Kaggwa asked the High Court to increase the fine given by the Lukiiko, but Justice Guthrie E Smith upheld the Lukiiko fine.

This was the first libel case in East Africa involving a native-owned newspaper.

In passing his judgment, Justice Smith said he “wished to encourage such a laudable enterprise as a native newspaper and not cripple it by imposing a too heavy fine”.

From its inception. Munyonyozi was critical of the Buganda Kingdom officials and fought for fair land redistribution.

And in passing judgment, Justice Smith put the newspaper’s criticism into consideration.

“Such criticism is entirely legitimate even though it may involve attacks on the policy of the government and the public officials. The law recognises the full liberty of the subject to comment on and criticise the conduct and motive of public men and it cannot be doubted that this is an advantage to the community and that even though injustice may often be done and though public men may often have to smart under the keen sense of wrong inflicted by hostile criticisms the nation profits by public opinion being thus freely brought to bear on discharge of public duties,” Justice Smith said.

Unfortunately for Bassude, this was not the end. He faced a series of libel cases in the Lukiiko, among which were accusations against Kaggwa of allegedly not being a Muganda; fathering 493 children from 51 women; being a non-Christian who worshiped fetishes, among others, for which he was fined 750 British Pounds.

As the court fines got high for Mugema, the publisher of Munyonyozi, they decided to part ways with Bassude.

Njubebirese newspaper

Kaggwa decided to print Njubebirese (the dawn). The editorial of its maiden issue read in part, “Our paper will always be in the middle. For instance, if the Kabaka makes a law, this law must be followed because it’s for the common good for the people in Buganda.”

Unfortunately for Njubebirese, it was short-lived. Writing in the 33 edition of the Uganda Journal of 1969, AJ Rowe said: “In the event Njubebirese did not last more than a couple of years. Nevertheless, it surpassed Apolo Kaggwa’s effort to launch a conservative newspaper in his press. The newspaper that was a stillborn was Bulungi Bwa Buganda (Buganda’s welfare) sponsored by Constantine Mukuye and Yusuf Bamuta.”

The native African press had ignored the colonial administration as though it did not exist, not until the colonial administrators decided to take over the collection of the luwalo tax (tax paid by every able-bodied Muganda man who did not want to work on public projects such as roads) that it came under criticism of the native press.

The White Fathers, a section of the Catholic missionaries, in 1912 launched a Luganda paper called Munno.

The declaration to take over the tax collection made Yusufu Bamuta, the editor of the Dobozi lya Buganda (voice of Buganda) newspaper, a strong critic of the colonial administration.

He argued that the culprits should be penalised as individuals and leave the natives to administer their own affairs.

Bamuta also criticised the mission schools which he accused of only providing education that was meant to keep Africans in subordinate positions.

“If the Europeans try to give us what they call African education, we shall oppose them tooth and nail. To attain the highest education the native must leave his country, the talk of Africans coming back de-Africanised is all rubbish.”

According to James Scotton, Dobozi lya Buganda’s editorials were seen as a challenge to the colonial authority.

“They represented in effect a call for Buganda nationalism,” Scotton says.

Working with the Lukiiko, the British sought ways to silence its critics. In 1931, Bamuta was accused of raping a 15-year-old girl, a daughter of one of the chiefs.

He was found guilty, a verdict the High Court upheld. Bamuta was sentenced to 10 months in jail.

With Bamuta way, the protectorate government silenced its critics.

After his prison sentence, Bamuta wrote: “I have done my best in a constitutional way and the result has cost me money, but I do not grouse. Truth will always come out and I’m sure it will prevail in spite of oppression.”