Prime

Shooting down Uhuru, Raila’s BBI, doctrine of basic structure, and case of Uganda

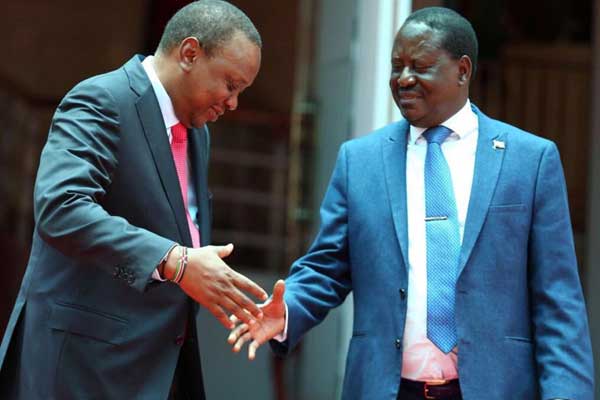

Ruling Jubilee and Orange Democratic Movement (ODM) parties say President Uhuru Kenyatta (left) and ODM leader Raila Odinga have directed party organs to transform the “handshake” - the truce between the rivals in the disputed 2017 presidential vote - into a formal coalition ahead of the 2022 elections. PHOTO / FILE

What you need to know:

- The Kenyan Judiciary recently threw out the Building Bridges Initiative (BBI) backed by President Uhuru Kenyatta and his former nemesis Raila Odinga, saying it’s in violation of the basic structure doctrine of the Kenya’s 2010 Constitution. Derrick Kiyonga & Joel Mukisa look into what this means for Kenya’s western neighbour, Uganda, where the concept isn’t yet fully resolved or even understood by judges.

Weeks after the Kenyan Court of Appeal shot down the Building Bridges Initiative (BBI) constitutional amendment Bill (2020) as illegal on grounds that if applied, it would profoundly alter the basic structure of the Kenyan 2010 Constitution, the ruling has reverberated all over East Africa.

Many now questioning where the judgement leaves Uganda’s jurisprudence. The basic structure doctrine has come out as the most salient issue with many in the legal circles wondering whether this judgment could be applied to all constitutions in East Africa as an authority.

The basic structure has been variously described as the foundation, the core, or the pillar of a constitution. The doctrine is said to be the brainchild of German professor Dietrich Conrad, who has since passed on.

Prof Conrad used the metaphor of pillars and described the basic structure of the constitution as the fundamental pillars supporting its constitutional authority. In February 1965, he delivered a lecture at the Banaras Hindu University in India, where he spoke on the theme of ‘Implied Limitation of the Amending Power.’

Prof Conrad’s lecture had an everlasting impact on India. The country’s Supreme Court in 1973, in the case of Kasevananda Bharti VS State Kerala – which has been lauded as the most important decision in the South Asian country – laid down that although Parliament has the power to amend, add, alter or rescind any part of the constitution, there are certain limits to this power.

The Indian court ruled that a national constitution has certain basic features, which underlie not just the letter but also the spirit of that constitution.

“These features constitute the sacrosanct core of the constitution, and any amendment, which purports to alter the constitution in a manner that takes away that basic structure, is void and of no effect,” the Indian judges ruled.

The rationale of the decision was that an amendment that makes a change in the basic structure of the constitution is not really an amendment but is, in effect, tantamount to dismemberment or replacement of the constitution.

The Supreme Court in India insisted that an amendment that makes a change in the basic structure of the constitution is not really an amendment but is, in effect, identical to maiming or replacement of the constitution.

Fast forward to Kenya where the stakes were high with the BBI being marketed since 2017 by former rivals Uhuru and Odinga as the tool that was to generally improve governance and thwart future post-election violence such as that which ensued after the 2008 and 2017 elections.

The famous March 9, 2018, Kenyatta-Odinga handshake led to the hatching of BBI, whose main agenda was to scrupulously scrutinise nine areas that were deemed by Kenyatta and Odinga to be critical to the creation of what they termed as “a united nation for all Kenyans living today and all future generations.”

The broad recommendations by the BBI included institutional reforms for streamlining the country’s institutions, particularly its constitution, and reintroducing a hybrid system of government that will include power-sharing between a president and a prime minister, with members of the Kenyan parliament allowed to serve as part of the Cabinet.

Perhaps to stress how the BBI agenda was inexorable, Odinga on the campaign trail co-opted South African reggae star Lucky Dube’s hit song, Nobody Can Stop Reggae. But the country’s Court of Appeal stopped the whirlwind campaign when it upheld the judgment by the High Court that implementation of BBI would alter the basic structure of the current Kenyan 2010 Constitution.

“Those who swear by the constitution must be prepared to live by it and defend it as commanded or else give the offices that come with such burdensome demands on their loyalties and consciences, a wide berth,” Justice Patrick Kiage of Kenya’s Court of Appeal stated.

“The proposals of the BBI were not amendments but the writing of a new constitution. Unamendibility is not eternity. Then Brazilian/ Portuguese terminology of clausulas petreas is more accurate as even rocks cannot withstand the volcanic outburst of the people’s primary constituent of power.”

In rejecting the BBI, Justice Daniel Musinga, who heads the Kenyan Court of Appeal, said: “Any amendment that alters the constitution fundamentally is not an ordinary constitutional amendment. It amounts to the dismemberment of the constitution.”

Case of Uganda

Before Kenya would grapple with the issue of the basic structure, it was Ugandan courts that were tested first in the consolidated petition that challenged the lifting of the presidential age limit from the Constitution.

Just like in Kenya, the stakes were equally high in Uganda as annulling the amendment would have brought to an end the reign of President Museveni, who has now been in power since 1986 and has removed terms limits from the Constitution.

The petitioners had contended that amending Article 102(b) of the 1995 Constitution to remove the presidential age cap would alter the Constitution since it would give Museveni a blank check to rule forever, a move, they said, would plunge Uganda into chaos, yet that’s exactly what the 1995 Constitution had sought to avert.

Arguing that lifting the presidential age limit went against the basic structure of the Constitution, Erias Lukwago, one of the petitioners’ lawyers, famously cited the preamble of the 1995 Constitution which says, “We the people of Uganda: Recalling our history, which has been characterised by political and constitutional instability…”

Although the five justices of the Constitutional Court unanimously stated that the basic structure doctrine was applicable in Uganda, they differed on what constitutes the basic structure.

Alfonse Owiny-Dollo, then Deputy Chief Justice, ruled that Article 102(b) is one of those that form the basic structure of the Ugandan Constitution.

Owiny-Dollo, now Chief Justice and head of the Supreme Court, said the provisions constituting the basic structure are the sovereignty of the people (Article 1), the supremacy of the Constitution (Article 2), democratic governance and practices, a unitary state, separation of powers, the bill of rights (under Chapter 4), and the independence of the Judiciary.

He argued that these are part of the basic structure because they are entrenched by Article 260 of the 1995 Constitution.

Justices of Uganda’s Supreme Court during the hearing of the age limit petition in April 2019. PHOTO | ABUKAKER LUBOWA

For Justice Remmy Kasule, who has since retired, what forms the basic structure in Uganda’s Constitution is the sovereignty of the people, the supremacy of the Constitution, defence of the Constitution (Article 3), and non-derogation of certain rights (not all rights). These, to him, are those encapsulated under Article 44, democracy, especially the right to vote, abolition of the one-party state, and independence of the Judiciary.

Justice Elizabeth Musoke limited her definition of the basic structure to the sovereignty of the people and the non–derogable clauses in the bill of rights; while for Cheborion Barishaki, emphasis was on popular sovereignty.

Justice Kenneth Kakuru, who was the lone ranger, having ruled to nullify the amendment, had the most expansive conception of the doctrine of basic structure, explaining that the question of whether or not the doctrine of basic structure applies, depends on the constitutional history and the constitutional structure of each country.

Every constitution, he said, is a product of historical events that brought about its existence.

The basic structure of Uganda’s Constitution, Justice Kakuru said, covers sovereignty of the people, the supremacy of the Constitution, political order through a durable and popular Constitution, constitutional and political stability based on the principles of unity, peace, equality, democracy, freedom, social justice and public participation.

He added that the rule of law, observance of human rights, regular free and fair elections, separation of powers, accountability of government to the people, non-derogable rights, the idea that land belongs to the people and cannot be taken away from them by the government without appropriate compensation, the idea that the State holds natural resources in trust for the people, the duty of citizens to defend the Constitution, and the abolition of the one-party state.

On whether Article 102(b) constituted part of the basic structure doctrine, the Ugandan Constitutional Court had to first determine where the specific Article (102b) fell under the three categories of amendments under the 1995 constitutional order, namely those that require a referendum for amendments to happen, including Article 1 on the sovereignty of the people, Article 2 on the supremacy of the Constitution, Article 44 on non-derogable rights, Article 69 which prohibits one-party state, Article 74 which spells out the rights for Ugandans to choose political systems, Article 79(2) which grants Parliament the power to make law, Article 105 on the tenure of office of the president, Article 128(1) on the independence of the Judiciary and Chapter 16 on traditional and cultural leaders.

Second category

The second category provisions are those that require a referendum if any amendment is to take place, but are different from the first category since they require approval of district councils and support of two-thirds of Members of Parliament and include Article 5(2), which provides for districts of Uganda, Article 152, which deals with tax laws, Articles 178, 189, and 197 that deal with the system of local government and their functions.

The third limb are those articles that require only two-thirds of Parliament to be tempered with and the Constitutional Court justices came to the conclusion that Article 102(b) was among these that simply required two-thirds of the Parliament.

Dissatisfied, the petitioners appealed to the Supreme Court, insisting that editing presidential age limits from the Constitution altered the basic structure of the 1995 Constitution.

Justice Mary Stella Arach-Amoko, in her judgment tried to strike a middle ground, saying the basic structure can only be found in those parts of the Constitution that the framers decided to entrench. Justice Arach-Amoko said the provisions in the Constitution can be touched as long as the procedure of amending them laid out in the Constitution is followed.

“While constitutions are intended to be both foundational and enduring, they are not intended to be immutable. If they are to endure, they must respond to the changing needs and circumstances of a country. To evolve and change with all changes in the society and environment is a necessity for every Constitution,” Justice Arach-Amoko said.

She added: “The 1995 Constitution was as a result of an elaborate and highly detailed constitutional-making process that involved all citizens. The framers of the Constitution did not, in my view, perceive the Constitution as an eternal document that could not be amended in any way. They were alive to the fact that the law was dynamic and could change with the changing society. It is for this reason that they provided for a methodology that is either rigid or flexible for amending the Constitution in two folds: Amending the Constitution through the participation of the people of Uganda (referendum). Amending the Constitution through the people’s representative (Parliament).”

Justice Eldad Mwangusya, one of the three Supreme Court justices that disagreed with lifting the age limits, asked what the fuss was the basic structure question.

“These Articles give a framework within which the Constitution can be amended. I do not think that it is necessary to agonise as to what the basic structure of the constitution is,” Justice Mwangusya said.

“As I have already stated both the Indian Court and the Constitutional Court attempted to define what the basic structure of the Indian and Ugandan Constitution is, but it was an exercise in futility,” he added.

“My understanding of the basic structure doctrine is that within this framework, the Constitution is amendable, but it can still be protected from compromise of its own foundation and structure so that every amendment is harmonised with the rest of the Constitution and the wishes of the people of Uganda.

“The framework provided under articles 259, 260, and 261 of the Constitution should not be seen as a licence to the Legislative arm of government to amend the Constitution the way they wish. As to whether this amendment was part of the basic structure, it was adequately addressed by the Constitutional Court, which came to the conclusion that the removal of the age limit would not affect the basic structure of the Constitution and I agree with that finding. The issue is answered in the negative,” he ruled.

Some of the judges of Kenya’s Court of Appeal during the hearing of the Building Bridges Initiatives (BBI) case last month.

In light of the Kenyan judgment, the judges in Uganda have been criticised as conservative and not willing to expand Uganda’s jurisprudence in a liberal manner.

“Well, the superior quality of analyses in the BBI case put our judges to shame,” lawyer Isaac Kimaze Ssemakadde said.

“The Ugandan decision was weighed and measured and it was found wanting. One Kenyan judge didn’t agree with the basic structure doctrine, but theirs was more deeply nuanced, clear, transparent and accountable. Our judges were, on the other hand, shambolic and fanatical,” he added.

Several justices of both the Constitutional and Supreme courts sought out to be interviewed for this article turned down the request, saying how the issue is extremely “controversial.” Some expressed fear that the basic structure question is not yet settled as other litigants can recycle it on other cases.

“Indeed, there was an attempt in the age limit case, but it’s understandable that a judge wouldn’t comment on such a matter because in future it can be brought again to court. So if the judge has already made his views clear then he wouldn’t sit on the panel. The Supreme Court can revisit its decisions; so it’s not yet settled,” constitutional lawyer Peter Walubiri said.

“India has a very complex constitution. The courts there are very radical because the federal structure ensures the cultural structure of the country,” a retired justice of the Supreme Court who didn’t want to be named said.

“The Constitutional Court is trying it [basic structure] in South Africa, and I think now they have no chief justice. So courts must be careful with how they handle it. Comparative constitutional law is good, but you have to know what you are talking about,” he warned.

Another retired Supreme Court judge said, “I didn’t know that it could turn out to be controversial. I made my judgement on the matter. Some people agree with it others don’t agree with it. I believe provisions of the Constitution can be touched as long as you follow procedures, so people can debate that, but for me, I ruled the way I ruled.”

“It’s has turned out to be controversial,” a male Justice at the Constitutional Court said. “I can’t openly comment about it because it might come back to court and I might be one of the judges on the panel. So I can’t make my views known, but it’s a good debate,” he concluded.

Doctrine of basic structure: Case of Uganda

Before Kenya would grapple with the issue of the basic structure, it was Ugandan courts that were tested first in the consolidated petition that challenged the lifting of the presidential age limit from the Constitution.

Just like in Kenya, the stakes were equally high in Uganda as annulling the amendment would have brought to an end to the reign of President Museveni, who has now been in power since 1986 and has removed terms limits from the Constitution.

The petitioners had contended that amending Article 102(b) of the 1995 Constitution to remove the presidential age cap would alter the Constitution since it would give Museveni a blank check to rule forever, a move, they said, would plunge Uganda into chaos, yet that’s exactly what the 1995 Constitution had sought to avert.