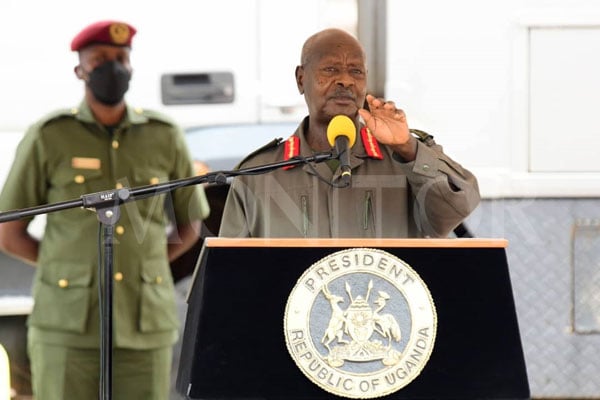

Prime

The evolution of Uganda’s Constitutions

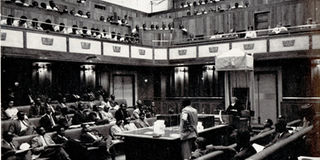

Parliament in session in the 1960s. In September 1967, Obote imposed a new Republican Constitution on the nation and declared himself president as all kingdoms were abolished. PHOTO / FILE

What you need to know:

- Beyond the banalities of the euro-centric independence Constitution, the NRM government and its Constituent Assembly delegates authored the 1995 Constitution, which smoothened the rough edges of the old document.

On the eve of independence, the gales of wind battered the Union Jack— the lasting vestiges of British imperial rule whose influence on Uganda as a colony receded in the background to pave way for a new order.

As preparations to hand over the government kicked off in earnest, the British organised the Uganda Constitutional Conference. Held at Lancaster House, it commenced in the autumn of September 18, 1961, and concluded on October 9, 1962.

The conference addressed some of the contentious issues on the eve of Uganda’s independence. Among the issues was the question of the Lost Counties—Buyaga and Bugangaizi—which had been annexed to Buganda from Bunyoro. The Lord Molson’s Commission treated the problem as a political question and not as a juridical contestation.

This conference organised by the British government was meant to pave the way for independence. The meeting largely focused on the report of Uganda Relationships Commission, which had been tasked with considering the future form of government best suited to Uganda and the question of the relationship between the central government and the other authorities in Uganda.

In addition to the UK government ministers, including Ian Macleod—the Secretary of State for the Colonies—the conference was attended by representatives of the colonial administration headed by Sir Frederick Crawford, then governor of Uganda, Buganda and Bunyoro kingdom representatives, the Democratic Party, the Uganda Peoples Congress (UPC), among others.

1962 Constitution flaws

The other sticking point facing the conference was the clamour for Buganda to be given a special status so that the kingdom would accept to be part of the new state of Uganda. In addition, the Kingdom of Bunyoro only agreed to participate in the conference if the disputed status of the “Lost Counties” was discussed.

When, during the conference, Macleod suggested that the referendum envisaged by the Relationships Commission could not proceed given the lack of Buganda support— instead proposing the establishment of a further Commission of Privy Councillors—Bunyoro’s delegates walked out.

The recommendations of the conference resulted in the Buganda Agreement of 1961, which supplanted the Buganda Agreement of 1955, as well as the first Ugandan Constitution.

A compromise position on the question of the Lost Counties was adopted during the British House of Lords debate on July 26, 1962, on the Uganda Independence Bill at Marlborough House. During the debate, there was a view that the atmosphere was quite unsuitable for holding a plebiscite in the Lost Counties before the promised date of independence.

“As your Lordships know, the view was urged in another place that there should be written into the Constitution a date before which the referendum must be held, or, at least, that a public declaration should be made in Uganda that a referendum will be held, without necessarily putting a date to it. An undertaking was given that these views would be put to Dr [Milton] Obote and this has been done,” reads part of the proceedings in the House of Lords.

By the end of the House of Lords meeting, there was a gridlock but in the view of the colonial power, they had attempted to forge the identity of a new state albeit major contradictions.

It is this document, which sieved the culture of natives through the narrow ‘repugnancy test’ based on euro-centric values and attempted to bring warring factions to hammer out a deal at Lancaster that gave birth to Uganda’s 1962 Constitution.

‘Pigeon-hole’ Constitution

Barely two years after independence, cracks emerged when Kabaka Edward Muteesa, who was the president, resisted the plebiscite in the Lost Counties. This later culminated in the Nakulabye Massacre of 1964 and later the 1966 Buganda Crisis.

On March 3, 1966, Obote dismissed the president and vice president and assumed the functions of the presidency. On April 15, the Constitution was abrogated formally during a parliamentary session in which army tanks rolled out and a ‘Pigeon-hole’ Constitution was adopted by MPs who had not even seen it beforehand let alone debated its contents.

The creeping coup had thus reached a crescendo when a military assault of the kingdom seat was sanctioned and the Kabaka fled to exile in the United Kingdom.

In September 1967, Obote imposed a new Republican Constitution on the nation and declared himself president as all kingdoms were abolished.

During this period of turmoil, Michael Matovu—the saza chief of Buddu in Buganda Kingdom—was arrested on May 22, 1966, and detained at Masindi Prison under the provisions of the Deportation Ordinance. He was subsequently transferred to Luzira Prison in Buganda Kingdom.

On May 23, 1966, a state of emergency was declared in Buganda by proclamation and this was later confirmed by the National Assembly, which also passed new legislation governing such states of emergency in the form of the Emergency Powers Act and the Emergency Powers (Detention) Regulations.

Matovu was released from prison on July 16, 1966, and ordered to leave. However, he was re-arrested upon stepping outside the prison and consequently re-detained, this time under the emergency powers laws.

In a landmark decision, the Constitution was put to test in the Uganda Vs Commissioner of Prisons ex-parte Matovu case that challenged the legal validity of the 1966 Constitution.

This decision introduced the legal juris Hans Kelsen’s “General Theory on Law and State” and the political question doctrine, which were considered during the hearing.

Kelsen stated that a change in a state’s “legal order” or basic norm by way of revolution or coup d’état, which is a means not within the contemplation of the deposed legal order or system, creates a new valid government or constitution if only the new legal order is efficacious in terms of control and recognition.

Even when some of the legal content or legal norms of the deposed regime, for example pre-existing laws, are preserved, they are in effect new norms because the reason for their validity has changed. Only their content is identical to the old norms.

Earlier the efficacy of this theory had been put to test in the Dosso Vs Federation of Pakistan where the Supreme Court applied it to determine that the Pakistani president’s annulment of the 1956 constitution and his imposition or declaration of martial law in 1958 amounted to a revolution that established a new legal order under which the law was to now be derived.

This theory gained traction across Africa and turned into a blueprint for those who conspired to rely on the barrel of the gun to stage military coups across Africa. Idi Amin swept to power in 1971 after staging a coup against Obote. He peeled off any veneer of pretence and ruled by fiat during a dark period, which came to be known as the reign of terror.

Today, the spectre of the ex-parte Matovu case continues to hang over the future of the country.

On November 12, 2015, Prof Joe Oloka-Onyango gave an inaugural lecture at Makerere University’s School of Law titled, ‘Ghosts and the Law’ where he spoke about the domineering presence of the ex-parte Matovu case in the arena of constitutional law and governance. He argued that the ghost appears in the form of the political question doctrine.

This doctrine refers to the idea that an issue is so politically charged that courts, which are typically viewed as the apolitical branch of government, should not hear the issue.

“But as with all spiritual beings—such as the Roman God, Janus—there are two sides to the case. In other words, there are not just one but (at least) two ghosts of ex-parte Matovu. There is the backward-looking one which supported the extra-constitutional overthrow of government in 1966 and paved the way for military dictatorship, judicial restraint and conservatism,” Prof Oloka argued.

He added: “And in the same case, there is its reverse which ‘jettisoned formalism’ to the winds, overruled legal ‘technicalities’, and underlined the need for the protection of fundamental human rights. The jettisoning formalism decision eventually opened the way to a robust and growing industry of public interest litigation in Uganda.”

1995 Constitution

Beyond the banalities of the euro-centric independence Constitution, the NRM government and its Constituent Assembly delegates authored the 1995 Constitution, which smoothened the rough edges of the old document.

In the preamble of the Constitution, the framers chronicle Uganda’s history peppered with political and constitutional instability and rely on the document’s structural edifice to anchor the principles of unity, peace, equality, democracy, freedom, social justice and progress.

However, after Parliament lifted the term limit and age limit provisions in the Constitution, there are fears that without the proverbial roots that nourish the tree, the Constitution as a living document could wither away and die.

Dr Benson Tusasirwe, who teaches at Makerere University School of Law, told Sunday Monitor that unlike the 1962 Constitution, which was midwifed at Lancaster, “We had for once established a home-grown Constitution. However, the document tells half the story. If the politics is of a consensus and consultation, the imperfections of the Constitution don’t matter. In Uganda’s case, it is meaningless in a society where power lies in the barrel of the gun.”

Dr Tusasirwe argues that perhaps the country was obsessed with enacting the Constitution as a document instead of Constitutionalism as a culture.

“There is a school of thought that [was amenable to] amending the Constitution. The exponents of this view wanted to have it as a living document. However, that theory doesn’t mean that you have to keep amending the Constitution to feed short-term interests, short-term gains undermine Constitutionalism,” Dr Tusasirwe reasoned.

“It creates uncertainty and the Constitution becomes a cheap document. It doesn’t follow the spirit of the Constitution. In the preamble of the Constitution, we talk of stability. This defeats the purpose and it resorts to the mechanical changes of the Constitution, it means that it lacks the capacity to intrinsically fit the circumstances.”

He opines that the lifting of term and age limit provisions in the Constitution flouted the basic structure doctrine.

“Amending routine provisions may not be necessarily bad if it goes to the root of the Constitution. The basic structure of the Constitution is not just the word, but the spirit. [It] doesn’t depend on the entrenched provisions of the Constitution; it depends on the character and purpose of the Constitution,” he revealed. “The provision to see peaceful transfer is part of the basic structure and the certainty it guaranteed is the smooth transition of power. Elections had failed to do this.”

An illusion

In his paper to mark 50 years of independence titled ‘The Illusion of the Uganda Constitution’ Busingye Kabumba, who teaches at Makerere University School of Law, opined that, “In my view, having regard to the constitutional, political and legal history of our country, I think it is fair to say that the 1995 Constitution is essentially an illusion. The illusion begins right from the first article which rather leads us to believe that ‘[all] power belongs to the people who shall exercise their sovereignty in accordance with this Constitution’ and runs on until the very last provision of that document.”

He further proffered: “The simple and unadulterated truth is that for a long time in our history, this has not been the case—and it is certainly not the case at present. If one asked the Ugandan citizen on the Kampala street where the power lies, I believe the answer would be that ‘all power belongs to the President, who exercises his sovereignty through the army.’”

He argues further that this is both the over-arching and omnipresent truth of our constitutional age, and also the source of the big lie that underlies the 1995 ‘Constitution’.

“For it is the gun and the capacity for, and ever-present threat of, the use of military force by the Executive that currently overshadows Parliament and Judiciary and creates the façade of democracy within which raw and unmitigated political power is exercised by an increasingly narrow group of people,” he says.

He cites the incident in June 2004 when the Judiciary was forcefully reminded after the Court of Appeal forgot its place in this ‘democracy’ and declared invalid the Referendum (Political Systems) Act of 2000, an angry Museveni informed them and the nation at large that the ‘major work for the judges is to settle chicken and goat theft cases but not determining the country’s destiny (sic)’.

“However, the final and decisive indignity for the Judiciary came on March 1, 2007, when, in response to the granting of bail to suspected rebels of the Peoples’ Redemption Army (PRA), a group of armed paramilitary men fittingly called the ‘black mamba’ surrounded the High Court, marched into the premises and even tried to forcefully enter the registrar’s office to ensure that the suspects remained behind bars. We were further reminded of this ‘command of the gun’ when later that year, in August 2007, referring to the 1996 elections, President Museveni told the long suffering people of Luweero that ‘had you elected Ssemogerere we would have gone to the bush.’”

Kabumba argues that it is not accurate to say the Constitution has been violated—the Constitution itself is naked, impotent and illusory.

“The gun is the real source of power and authority in contemporary Uganda. All power belongs to the President Museveni, who exercises this power through the armed forces. Article 1 of the Constitution is a lie—and the Constitution in Museveni’s Uganda is an elaborate farce that is cynically perpetrated by the President to consolidate and extend his hold on power. This is one of the great tragedies and challenges of ‘Uganda at 50’ and one that promises to engender more turbulent chapters in our political life.”