Why officials lose sleep when church leaders talk politics

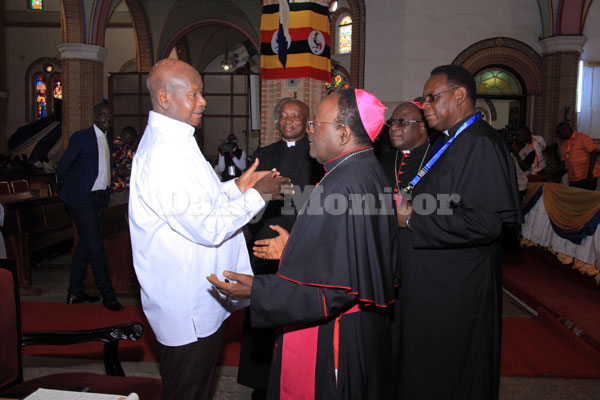

President Museveni (left) meets religious leaders during the African Bishop’s conference in July 2019. PHOTOS/ FILE, RACHEL MABALA

What you need to know:

- Coming against a backdrop of unequivocal demands by President Museveni that religious leaders must leave politics to politicians, his revelations during Archbishop Kizito Lwanga’s funeral service at the Kololo Independence Grounds has only served to return the debate on whether or not religious leaders should be engaging in politics, or making pronouncements about matters politics.

On Tuesday, President Museveni revealed that the late Archbishop of Kampala Cyprian Kizito Lwanga, his predecessor, Cardinal Nsubuga, and other religious leaders had been supportive of the National Resistance Army’s (NRA’s) five-year Bush War.

“(Cyprian) Lwanga was part of our bayekera sympathisers. We were in the bush fighting but we had sympathisers who did not shoot guns, but they prayed for us. They were with Cardinal Nsubuga, Bishop Yokana Mukasa and Muslim leaders like Badru Kakungulu. They were part of our sympathisers,” Mr Museveni said.

Mr Museveni revealed that the Cardinal had provided logistical support to the NRA.

“In particular Cardinal Nsubuga had two points which we utilised without his official consent, including a ranch in Kyankwanzi where we would get medicines from…,” Mr Museveni said.

Coming against a backdrop of unequivocal demands by Mr Museveni that religious leaders must leave politics to politicians, his revelations during Archbishop Kizito Lwanga’s requiem mass at the Kololo Independence Grounds has only served to return the debate on whether or not religious leaders should be engaging in politics, or making pronouncements about matters politics.

One can argue that by contributing to an armed rebellion, the clerics were making a political statement of mega proportions. One can in the same breath argue that by accepting their support, Mr Museveni and his rebels were acknowledging the fact that the fight for greater democracy, human rights and governance is not the preserve of career politicians and self-arrogated freedom fighters but that it is one that clerics can participate in as citizens of Uganda.

It would, therefore, appear strange that someone who was in yester-years okay with the religious leaders’ contribution to his war effort would in subsequent years become averse to seeing them comment of developments in the same polity.

What is it that makes Mr Museveni uncomfortable with them participating in politics?

Is NRM afraid of the Church?

Prof Sabiti Makara, who teaches Political Science at Makerere University, argues that it is down to fear of both the numbers that the Church can reach out to at any given one time and the fact that the public is inclined to believe clerics more than it would politicians.

Metropolitan Jonah Lwanga.

“They usually speak to very large audiences and if they were to keep pointing out the wrongs and abuses of a system, that has capacity to cause change,” Prof Makara argues.

Prof Makara has a point. Days after the January 14 election, the minister for the Presidency, Ms Esther Mbayo, revealed that government had evidence that the Catholic Church had actively campaigned against Mr Museveni, especially in Buganda where he lost to the candidate of the National Unity Platform (NUP), Mr Robert Kyagulanyi.

Former Forum for Democratic Change (FDC) president Kizza Besigye had in previous elections defeated Mr Museveni in Wakiso and Kampala, but Mr Museveni would always win the Buganda vote. This time round he lost the Buganda vote with a margin of 614,677 votes. Mr Museveni got 838,858 votes, while Mr Kyagulanyi got 1,453,535 votes.

The NRM also lost a huge number of parliamentary seats. The biggest political scalp was that of the Vice President, Mr Edward Kiwanuka Ssekandi.

It would be understandable if it were out of fear that some people would like to silence religious leaders. The church has been quite influential in shaping political developments in neighbouring Kenya and the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC).

For example, in the late 1980s as the political space shrunk in Kenya under President Daniel arap Moi, it was the Anglican Bishop, Alexander Muge, who took the lead in calling for reforms. Cardinal Maurice Michael Otunga and Archbishop Raphael Ndingi Mwana Nzeki of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Nairobi took the lead in demanding reforms after Muge’s death in August 1990. That led to a return to multiparty politics in Kenya.

Former Assistant Bishop of Kampala Diocese Zac Niringiye

In DRC, Joseph Kabila had delayed holding elections after his two constitutional terms expired in 2016 on grounds that the country did not have money and that there were problems with voter registration. It was after the Church joined in non-violent protests that Mr Kabila was forced to organise elections in December 2018. He handed over power to Felix Tshisekedi in January 2019.

State minister for Cooperatives, Mr Fredrick Ngobi Gume, does not believe that it is out of fear that some people would like to see the religious leaders keep off politics.

“Whereas the Church can be very influential, I still think that one can influence the politics by addressing those things that the people consider necessary for their survival and wellbeing. That can, for example, be seen from the way Kaliro, Namutumba and Buyende districts voted and returned Mr Museveni and also voted for NRM parliamentary flag bearers, which was not the case in the rest of Busoga,” Mr Gume says.

During the January vote, Mr Museveni was beaten to the vote in Busoga sub-region. He got 404,862 votes against Mr Kyagulanyi’s 437,059 Votes. Mr Museveni won in only three out of Busoga’s 11 districts. He won in Buyende, Kaliro and Namutumba, but beaten hands down in Kamuli, Luuka, Iganga, Jinja, Bugweri, Bugiri, Namayingo and Mayuge districts.

“Whereas we in Bulamogi North West also have wetlands from which people were evicted and a lake to which they were denied access, a lot had been done in terms of service delivery. Until about seven years ago, we had no secondary schools, but we now have a seed government school and three other secondary schools and the number of sub-counties has been increased from one to three, the number of Health Centre IIIs increased from one to three and the process of rolling out electricity is on,” Mr Gume says.

Mr Gume says it is such services and not what a church leader might say, that influences the politics. One then wonders why people will not sleep easy when the men of the frock start talking politics.

Prof Makara says the argument that religious leaders should not be allowed to talk politics smacks of hypocrisy.

“When they speak in favour of President Museveni and the NRM, their comments are deemed to be alright. But when they talk in a manner deemed to be critical of the government, it is said to be wrong. But religious leaders worldwide are by their position and possibly training political. The right thing is for political leaders to speak out openly about whatever is going in the country,” Prof Makara argues.

Unwelcome criticism

Religious leaders were some of the most outspoken critics of Parliament’s December 20, 2017, vote on Constitutional Amendment Bill No2 of 2017 which resulted in the deletion of Article 102(b) of the Constitution to allow Mr Museveni to contest for the presidency after removal of the upper age limit of 75 years.

Most of the 2017 Christmas Day sermons suggested that most Church leaders believed that Parliament’s decision was always going to be a recipe for political disaster. The criticism did not sit well with Mr Museveni who called them out for alleged “arrogance” and making pronouncements about matters that they were least competent to comment on.

The church leaders did not take the comments lying down. Metropolitan Jonah Lwanga, leader of the Orthodox Church, reminded Mr Museveni that it was not for his government to grant or determine the right to speak, while Archbishop Kizito Lwanga, admonished those who he said were trying to muzzle the Church.

“The remarks we make are none other than those telling the truth because the Church is the conscience of the State. So please see us as your conscience and we shall continue being a good conscience,” Archbishop Kizito Lwanga said.

Long history of trying to muzzle church

That was only one of the phases in a long history of attempts to gag religious leaders, especially when Mr Museveni seemed to be on the receiving end.

In 2002, he said he was likely to start baptising children given that the clergy were spending more time on talking politics than “delivering souls to heaven.” Those comments were precipitated by the contents of sermons that some of the clerics gave during the Easter 2012 prayers.

Archbishop Kizito Lwanga, had in his sermon advised Mr Museveni not to contest in 2016 and instead preside over a peaceful transfer of power, describing it as “the best present Museveni can give to Uganda in 2016”. Former Assistant Bishop of Kampala Diocese Zac Niringiye and Metropolitan Lwanga had similar messages.

Mr Tamale Mirundi, who was then Presidential Press Secretary, shouted the religious leaders down.

“The problem with those people is that they do not know their role. A bishop cannot tell a medical doctor to make a woman deliver through the mouth because that is not his role. In the same way they should not instruct Museveni on political issues because that is not their specialty,” he said.

Not innocent

The Church can, however, not be said to be entirely innocent when it comes to aiding the State in trying to keep it out of the politics.

For example, in 2010, the House of Bishops of the Anglican Church passed a resolution that barred ordained persons or commissioned workers from participating in elective politics, on showing open support for any political party or holding a party card.

Any member of the clergy who wishes to join elective politics is required to first resign. It was an account of that resolution that Bishop Niringiye opted to retire seven years before the official retirement age had come.

Confusing signals

The problem though is that Mr Museveni has been giving conflicting signals about the extent to which religious leaders can participate in politics.

He, for example, appointed a Catholic priest, Fr Simon Lokodo, as the Minister for Ethics and Integrity. Fr Lokodo has been contesting on an NRM ticket.

During the 2018 New Year address, Mr Museveni indicated that sections of the clergy were intent on imposing what he termed as pseudo-democracy, but Prof Paul Wangoola, who was a member of the National Consultative Council (NCC), which served as an interim Parliament following the fall in April 1979 of the Idi Amin regime, thinks that it is actually the NRM under Museveni that is practicing pseudo-democracy.

“He doesn’t want dissent. That is a characteristic of all dictators and all of them start with silencing dissent within. That is why he is not happy that there were some NRM MPs who voted against the constitutional amendment, or that the Church often takes certain stance,” Prof Wangoola told Sunday Monitor in a previous interview.

The debate about whether to let the clerics talk politics is not about to end.