Grobbelaar endured war, doubt and disaster to become a hero

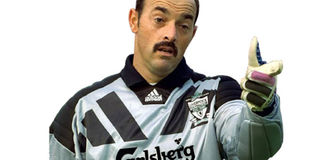

Anfield hero. Grobbelaar is a legend at Liverpool. PHOTO/AGENCIES

What you need to know:

Influence. The Zimbabwean goalkeeper is one of the most celebrated players in the history of Liverpool

A sports academy is the ideal place for any aspiring sportsman. It’s where teenagers develop their skills, ahead of their more arduous senior careers. Bruce David Grobbelaar – the first African to win the European Cup (now Uefa Champions League) – was on the same trajectory but was conscripted into the Rhodesian army in 1975, aged 18, to fight for the White Supremacists in Zimbabwe’s War Of Independence.

Born in Durban, South Africa, to Afrikaner parents, Grobbelaar was two months old when he, his mother and sister moved to Rhodesia (present-day Zimbabwe), where his father worked with the railways.

Talented in baseball and cricket, Grobbelaar loved football more, turning up for Highlanders in Harare in 1973 and Chibuku Shumba. But just before his international debut for Rhodesia at 19, came the duty to kill.

In his 2018 book, “Life in a Jungle,” Grobbelaar retold of the gruesome memories of war, as his fellow white combatants battled black freedom fighters.

“This guy would cut an ear off every man he killed. He kept the ears in a jar. And he had quite a few jars. His family had been brutalised so he wanted revenge,” he recalled.

Grobbelaar also recalled of the distraught soldiers taking their own lives. They had completed their conscription but were forced to do another six-month tour of duty.

“They couldn’t face it.”

Grobbelaar was lucky. “Football kept me away from the dark thoughts of war.”

And football had made him popular in the black townships. “The fans called me Jungleman. They said this young guy’s not white. He’s black in a white man’s skin.”

Long walk to Anfield stardom

Having stretched his youth career into South Africa until 1978, Grobbelaar begun his protracted journey towards English football. First, he impressed in a trial at West Bromwich Albion but did not get a work permit and was due to return home five months later.

But in November, after traversing three continents in four days and playing two trial games in two days with the Vancouver Whitecaps, in Derby, England, the Canadian side signed Grobbelaar on a one-year contract.

Failure to dislodge former West Ham keeper Phil Parks sent the 20-year-old Grobbelaar on loan to Crewe Alexandra, in the English Fourth Division, where he scored a from the penalty spot in his last game.

When Parks joined Chicago Sting in 1980, Grobbelaar became regular to impressive effect. Bob Paisley, Liverpool’s manager, was among the most notable admirers and took Grobbelaar to Anfield to replace the departing Ray Clemence.

Grobbelaar took time to fit in the giant shoes of a man who boasted 500 appearances for the Reds since 1967. The Kop were unforgiving, some yelling obscenities at their new faltering custodian.

“It hurt that they [the insults] were from our own supporters,” Grobbelaar said in his first autobiography, “More Than Somewhat.”

When Liverpool lost 3-1 to Manchester City on Boxing Day of 1981, Paisley engaged his goalkeeper in a serious talk. “He just said to me: ‘How do you think your first six months have gone?’ I said: ‘It could have been better.’ And he said: ‘Yes, you’re right. If you don’t stop all these antics, you’ll find yourself playing for Crewe again.’”

There could be no better warning. Grobbelaar stamped his authority in the most successful team in England, with 317 uninterrupted games between his debut on August 29, 1981, and August 16, 1986.

There was that kangaroo-like jump, in the 1986 FA Cup final when teammate Alan Hansen’s clearance was headed straight at goal with Grobbelaar out of position. But his most unforgettable moment remains his performance in the European Cup final of 1984 when his antics put off the most experienced Italians in the penalty shoot-out as Liverpool beat AS Roma 4-2 in Rome.

“[Manager] Joe Fagan had his arm around me when I was going to the goal and said: ‘Listen, myself and the coaches, the chairman and the directors, your fellow colleagues and the fans are not going to blame you if you can’t stop a ball from 12 yards,” Grobbelaar later revealed. “‘Try to put them off,’” Fagan told him.

He did just that. Extra time ended 1-1. Grobbelaar did not save any of Roma’s four spot kicks. But his spaghetti-legs antics made two Roma players miss and when Francesco “Ciccio” Graziani’s kick hit the crossbar and ricochetted off, Grobbelaar paced in celebration, before Alan Kennedy netted the winner.

Grobbelaar became the first African to win the European Cup – which later became the Champions League.

Polish goalkeeper Jerzy Dudek would replicate the antics as Liverpool won the shoot-out against AC Milan in the dramatic Champions League final in 2005.

Grobbelaar and this dominant Liverpool could have won more. But surprisingly ended the 1984-85 season empty handed. They dropped out in the League Cup Third Round; lost the FA Cup semis to Manchester United, surrendered the league to title to Merseyside rivals Everton before losing the European Cup final 1-0 to Juventus.

But the Heysel disaster, which killed 39 Juventus fans and injured 600, just before the final, hurt even the more. English clubs were banned from European competitions until 1990. Liverpool until 1991.

But in between, an even bigger disaster killed 96 Liverpool fans in at Hillsborough Stadium in Sheffield in 1989.

“It was worse [than war],” Grobbelaar recalled the incidents in an interview with The Guardian. “In the bush you knew what could happen. At Heysel it was innocent people. To hear the crumbling wall and the falling bodies was terrible.”

A girl called Jackie, whom he had given the game ticket nearly died but luckily survived and attend Grobbelaar’s book signing in 2018.

Match fixing scandal

In 1994, Grobbelaar was alleged to have been paid £40,000 by a Far East betting syndicate for throwing a match Liverpool lost 3-0 against Newcastle United on November 21, 1993, in which Andy Cole scored a hat-trick in the opening 30 minutes.

The same allegations were attached to some games when he went to Southampton in 1994.

Bob Wilson, who had kept Arsenal’s goal at least 300 times, then a TV soccer pundit, was hired to review tapes of the games in question: Newcastle-Liverpool; Liverpool-Manchester United; Norwich-Liverpool; Coventry-Southampton; and Manchester City-Southampton.

Wilson found no evidence of match-fixing, telling the jury that in the Newcastle game, Grobbelaar had virtually no chance with the three goals and he had made three excellent saves.

In the 3-3 draw against Man United, Wilson reported, Grobbelaar had made two saves that were of the highest order at any level in the world, which had kept his side in the game. He could not have saved the two goals scored against him by Norwich and made a “truly outstanding” save.

In 1997, the jury declared Grobbelaar, and Wimbledon pair John Fashanu and Hans Segers not guilty on all accounts.

Grobbelaar sued The Sun that published the allegations for libel. Court awarded him a £85,000 settlement but when the tabloid appealed, the court ordered Grobbelaar to pay the newspaper’s £500,000 legal costs which left him bankrupt.

In his 2018 book, “Life in a Jungle,” on which The Guardian’s Donald McRae interviewed him in October 2018, Grobbelaar accuses Chris Vincent, his former colleague in the Rhodesian army, of conning him into the saga. He said Vincent had earlier conned him of millions in a stealth business deal.

Now he returned with a deal “to get my money back.”

Vincent suggested two guys in Hong Kong who will “give [me] money to throw a game. I thought: ‘Let’s see where he’s going with this.’”

Grobbelaar claims he wanted to know who the people behind the deal were and report them to the authorities.

“But he got there first.”

But wouldn’t the wiser option be walking away from trouble? Well, to borrow his response to killing people during war, “I can only say sorry for the past. I can’t change it.”

After guiding Liverpool to what became their last domestic league title for many years in 1990, Grobbelaar gave way for the emerging David James. First, he was loaned to Stoke City in 1993, returned for a season before joining Southampton on a free transfer at the end of the 1993/94 season.

His antics and carefree attitude endeared him to many. But some felt he sometimes was too casual for life, and somehow cost his team. But that is the best he chose to live, even in the jungle.

“I never did get used to killing other men even if they were hell bent on doing me as much harm as possible,” he wrote in his first autobiography.

“If war teaches you anything it is an appreciation of being alive and I will never apologise for laughing at life and enjoying my football,” he writes.

Although he enjoyed a stellar career at Liverpool, fetching 19 titles (six of which in the league, and one European Cup), his 32 caps on the Zimbabwean national team achieved little.

Alongside the Ndlovu brothers Peter and Adam, Grobbelaar formed the so-called “Dream Team” that promised to take Zimbabwe to their first ever World Cup but it never happened.

Nevertheless, Grobbelaar is an African hero, one who triumphed over war, racial prejudice and doubt on the pitch.

At a glance

Bruce Grobbelaar

Born. October 6, 1957 (age 62) POB. Durban, South Africa

Height. 6 ft 1

Playing position. Goalkeeper

International (1980-98): 32 appearances for Zimbabwe

Post-retirement. Coaching

HONOURS

Liverpool

Football League First Division: 6

FA Cup: 3

League Cup: 3

FA Charity Shield: 5

European Cup: 1983–84

Football League Super Cup: 1986

[email protected]