2,000 doctors leave country in 10 years

Doctors at Mulago hospital operate a patient. According to health officials, many medical practitioners leave the country because they are frustrated by lack of equipment which cripples their morale. PHOTO BY Faiswal Kasirye

What you need to know:

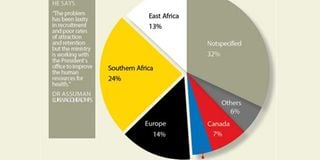

Only 1, 200 doctors of those licensed are said to be practicing in Uganda while some are working in the neighbouring countries of Rwanda, Kenya, Tanzania, South Sudan, and South Africa. This number also includes doctors in management, administrators, lecturers and tutors, district health officers and Members of Parliament who are doctors. Others unaccounted for include those working in countries that are unstable like Somalia, Somali land, Swaziland and Botswana.

Kampala

South Sudan is the latest destination for Ugandan trained doctors whose migration for greener pastures has for long become an open secret.

Latest statistics from the Uganda Medical and Dental Practitioners Council, indicate that more than 2,000, nearly 50 per cent of the registered number of medical practitioners, have left the country in the past 10 years even as the government continues to struggle to attract, recruit and retain doctors in State health facilities.

The Council had 4,200 registered doctors as of July 31, 2013. Out of these, only 2,021 have been licensed by the Council, while only 1,200 are involved in clinical medicine, a role for which they are trained.

Despite fears in the sector that the latest trends do not show any efforts to curb the long lasting problem, authorities say they are moving to deal with the issue once and for all.

“We realised that there is external market for health workers if they are not handled well. In South Sudan, Rwanda, South Africa and in Uganda there is market,” the Permanent Secretary in the Ministry of Health, Dr Asuman Lukwago, said.

According to the latest figures, most of the unlicensed doctors are suspected to be ending up in the South Sudan market where the doctors do not need a practicing licence to do work, mostly in donor funded projects.

Dr Ssentongo Katumba, the registrar at the Uganda Medical and Dental Practitioners Council, confirmed some 2,021 registered health doctors are not known since they are not involved in clinical work, because they have moved to the private sector or migrated to well-paying markets. “Some of them may be in the country, but doing other things not related to medical work. Many others have absorbed into the donor-funded projects while others are doing private work,” he said in an interview.

Only 1,200 doctors of those licensed are said to be practicing in Uganda while some are working in the neighbouring countries of Rwanda, Kenya, Tanzania, South Sudan, and South Africa.

This number also includes doctors in management, administrators, lecturers and tutors, district health officers and MPs who are doctors. Among other factors depleting the health sector of practitioners, Dr Katumba says, is that most doctors who go for further studies in other countries, nearly 70 per cent do not return and when they do, they join projects due to poor pay in the public health sector.

“Up to 32 per cent of Ugandan doctors have not specified the countries in which they are working. For instance we aware that South Sudan is employing over 200 Ugandan doctors but they don’t appear in our system because South Sudan does not have a medical council nor do they require recommendations from the Ugandan council before they take them up,” Dr Katumba says.

Other unaccounted for include those working in countries that are unstable like Somalia, Somali land, Swaziland and Botswana. Dr William Mbabazi, a Ugandan doctor working as the Head of Health/Measles Delegate at the American Red Cross based in Nairobi, says the trend is driven by personal, push-and-pull factors for different individuals to different countries.

“In Uganda’s case there are more of push factors and in my case it was frustrating to work with a non-responsive health care system. If you are a progressive person, you will find it hard to work in the Uganda’s setting,” Dr Mbabazi told the Daily Monitor in a telephone interview yesterday, adding that the country’s health sector did not offer him challenges after working for over 18 years.

While his choice to work in another country is not based on payment, a Ugandan medical officer currently working in Maseru, the capital of Lesotho in South Africa says he left the country to seek for green pastures because of poor pay.

The source says before he left Uganda, he was being paid a net pay of Shs500,000 as his monthly pay compared to his current salary of Shs10 million, a house and he is exempted from car tax.

Figures obtained from the Ministry of Public Service indicate that medical officers in Uganda are paid a gross of Shs846,000, consultants Shs1.3m while senior consultants earn a gross pay of Shs2.3m. While in Rwanda, for instance, the starting salary for a medical officer is Shs3.8 million.

In Kenya, consultants are paid an equivalent Shs7.8 million while senior consultants take home a net salary of Shs10 million. Tanzania pays Shs13 million as salary for a consultant.

Health sector still faces daunting challenges

Other reasons medical practitioners leave include lack of equipment. Someone trains to become a brain surgeon, when they come to Uganda, they are frustrated because there is no equipment and no team to work with.

“They end up frustrated. This kills their morale,” Dr Margaret Mungherera, the president of the Uganda Medical Association, says

Every year, a combined number of 260 doctors graduate from Makerere, Gulu and Mbarara, Kampala International universities and a few graduate from outside the country. But of 260 who graduate every year, less than 50 per cent join the public sector.

Dr Mungherera says that this trend is very dangerous and if not addressed urgently, the future of the medical and health sector is at stake.

She adds that the indicators will remain poor because the available few doctors are paid poorly yet the work load is too much.

This number is not small, according to Dr Lukwago, the Permanent Secretary Ministry of health. “The problem has been laxity in recruitment and poor rates of attraction and retention, but we have identified the gaps and the ministry is working with the Office of the President to improve the human resources for health,” he said.

Another senior consultant at Mulago hospital, who preferred anonymity, says as a result of poor pay, almost 100 per cent of consultants and senior consultants have taken on “moonlighting” a common phrase to mean doing two jobs at the same time.

Corruption

“This is the highest form of corruption in health sector emanating from poor pay. It leaves patients desperate as doctors are now chasing money.”

This, the senior consultant, says is robbing patients of time that they are supposed to be seen as well as affects service delivery. The source says this means that patients who cannot afford to see the doctors in the private hospitals and clinics are left unattended to.